On the 23rd of March this year, the RBA published an academic discussion paper that detailed their Financial Conditions Index (FCI) and Growth-at-Risk (GaR) modelling.

This was one of the RBA’s first steps to produce a comprehensive narrative that financial conditions have become more restrictive as bond yields rose and yield curves steepened, that was a cause of concern for the Bank, where conditions have moved from “expansionary” to “restrictive”.

If you were a keen RBA observer like we are, and read our summary notes the following week, then much of the RBA’s testimony this year would’ve been expected and perfunctory.

The RBA then extended the narrative yet again in May, publishing another academic discussion paper detailing their communication approach, and how they were modifying their approach to provide more readable publications, which could be understood by audiences of varying technical understandings of economics.

In our summary on June 7th, we were able to connect more dots, going one step further, where we believed we could reasonably determine the RBA’s policy easing timetable.

As a summary, we believe the RBA has adopted this rubric, to communicate their relative policy stances:

#1 Release an academic paper discussing policy initiatives and likely effects

#2 Publish articles about possible RBA policy movements using friendly sources to the RBA, such as the AFR or The Australian, where non-RBA members would further the conversation and shape public opinion

#3 RBA members would then speak at events and suggest what the RBA may do, if and when economic data approaches their target thresholds

#4 Assess the reaction of the market based on #1-3, and if no significant tantrum within financial markets, then look to move ahead and propose the time frame to adopting this new policy, likely a couple of months in the future

And this isn’t just the RBA either, we can see the same framework utilised in the US Federal Reserve’s narrative building exercises, the latest update summarised in our notes of the Jackson Hole Symposium two weeks ago.

The Phillips Curve

Upon seeing yet another academic discussion paper published by the RBA last week, regarding our domestic unemployment rate and wages, it was immediately a must-read in our opinion, as it might provide the next insight into the RBA’s psyche.

In advance, the article was regarding the Phillips curve, an economic concept named after William Phillips, stating that inflation and unemployment have a stable and inverse relationship.

I.e., as demand for workers (labour) increases, the pool of unemployed workers subsequently decreases, and companies offer higher wages to attract new hires from the shrinking pool of available talent. After which, the increasing input costs of salaries and wages into business models would result in higher prices throughout the economy, otherwise known as inflation.

RBA Viewpoint

From the RBA’s own summary notes of the paper, they asked:

“A key policy question facing the RBA Board is: when will unemployment be sufficiently low to generate a sustained increase in wages growth?

Understanding the shape of the relationship between unemployment and wages at very low rates of unemployment is essential in helping to answer this question, particularly given the RBA’s central forecast for the unemployment rate to fall to a four-decade low over the next few years.”

This is obviously a key insight into what the RBA Board is seeking as an outcome, keep that in your mind.

As for the discussion paper?

The key conclusion was underwhelming in that while wage growth will generally increase as unemployment falls, it is unlikely to accelerate quickly even if we reach historically low levels of unemployment, where inflation would therefore be unlikely to accelerate sustainably higher and require the RBA to tighten monetary policy.

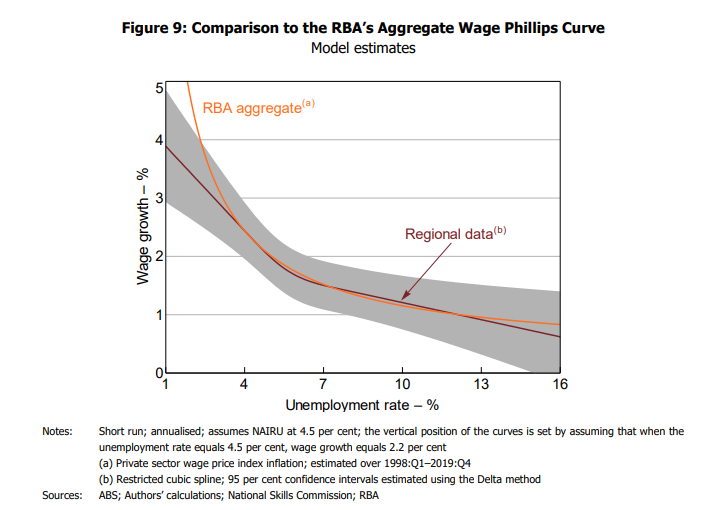

Visually we see this in the below, where in the model’s sample period, income growth (Y-axis) does not accelerate too quickly even when unemployment reaches historically low levels (X-axis) – which in Australia, would be any period when unemployment is below 5%.

Moreover, the modelling reinforces what the RBA has been saying for several years already, that wage growth is less responsive to lower unemployment rates, because we have a material degree of slack within our domestic labour market, which we can measure with the underemployment rate or the utilisation rate.

This creates a flatter Phillips Curve, highlighting less chance of wage growth.

Past Performance =/ Future Performance

At this point I was reading through the analysis trying to find a link from this model – which uses historical data – to the RBA’s forward-looking projections.

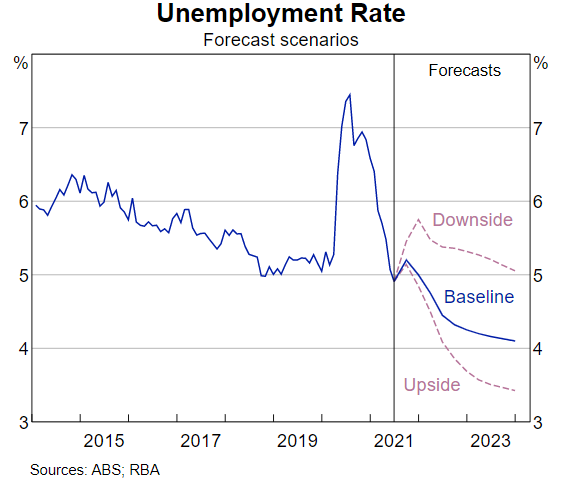

This brings us to the of the RBA’s Statement of Monetary Policy (SoMP), where they published their forecasting for the unemployment rate, where their baseline assessment is for the rate to trend towards ~4.5% over the coming two years, and therefore – connecting the dots – they’re not foreseeing any sustainable spike in inflation, because of the flatness of the Phillips Curve, because of the slack within labour markets at present.

This makes intuitive sense, where the short-term dynamic as a result of the pandemic is from labour supply shortages causing bottlenecks and supply-constraints, creating short-run inflation, rather than sustained, longer-term inflation.

The RBA Remains Dovish

What this means is that the RBA is likely to remain reasonably dovish and stick to their 2024 guidance that if the unemployment rate falls towards 4% (as per August SoMP), then it’ll take a lengthy time to see wages sustainably grow at a faster rate.

Referring to the August SoMP yet again, the RBA baseline scenario is for inflation to reach 2.25% p.a. at the end of 2023, even with unemployment declining to a mere 4%.

The “upside” scenario had unemployment declining to 3.5% (an all-time best for our nation), with inflation only reaching 2.75%.

This resonates with us, as we detailed on 12-August, that Inflation is Psychological, and requires a change in the collective mindset of consumers, business owners and investors.

John Maynard Keynes referred to this behavioural finance relationship as “animal spirits”, which is coined in his 1936 book “The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money” to describe the instincts, proclivities and emotions that influence human behaviour.

In summary, this all reinforces that the RBA will likely stick to their ‘slowly but surely’ policy implementation, where they’re currently in no rush to remove the emergency level of policy accommodation that’s been in place since March 2020.

To close, since I penned this note at ~12pm yesterday, the RBA released their latest Monetary Policy Decision at 2:30pm and extended their bond purchase tapering from a $1 billion per week reduction with a review in Q4, to February 2022, a dovish surprise.

Certainly in no hurry to tighten policy.

The views expressed in this article are the views of the stated author as at the date published and are subject to change based on markets and other conditions. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Mason Stevens is only providing general advice in providing this information. You should consider this information, along with all your other investments and strategies when assessing the appropriateness of the information to your individual circumstances. Mason Stevens and its associates and their respective directors and other staff each declare that they may hold interests in securities and/or earn fees or other benefits from transactions arising as a result of information contained in this article.