The story so far

In response to the crisis and subsequent financial market crash, global central banks engaged in policies aimed at increasing liquidity within markets and attempting to promote economic growth and stability.

Accommodative monetary policies included low-interest rates, asset purchasing programs (quantitative easing), and adjusted short-term liquidity operations.

In return, the market rebounded and maintained the relative level of support and liquidity which was the original desired outcome of the monetary policies, to begin with.

The above-italicized section could very easily apply to current circumstances, in fact, one could argue it applies most relevantly to the events of 2020 and 2021.

However, it is in fact an abridged summary of the 2008 global financial crisis (GFC) and subsequent recovery of financial markets, with the support of central banks throughout.

A key reason to draw this parallel is a term that has been floating around financial media over the last few months of a “taper tantrum”, in relation to if/when central banks will indicate to the market that they will be slowing down their rate of quantitative easing and returning to a more ‘normal’ state of monetary policy.

With this in mind, it seems prudent to go over the leadup to the 2013 “Taper Tantrum” and its effect on markets, as an insight into if it is likely in today’s environment and potential outcomes if something similar does occur.

The Taper Tantrum

Most readers will remember the effect of the GFC, not only on the livelihoods of people around the world but also on financial markets and the performance of trillions of dollars in assets.

From what is generally considered to be the start of the GFC crash, with the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers in September 2008, the S&P 500 fell ~44.3% down to its lows in March 2009 – as a point of reference, the S&P 500 fell ~30.7% in Q1 last year during the COVID-19 crash. This came on the back of what was a market only just recovering levels seen before the dot-com bubble of 2000.

As one response to the subsequent economic and financial market disaster that was the GFC, the U.S Federal Reserve implemented an asset purchasing program (also known as quantitative easing) in order to buy US Treasury notes (bonds) and mortgage-backed securities, in an attempt to provide liquidity to the market and promote stability.

The level of assets held on the Fed’s balance sheet ballooned in the subsequent three years, as seen below:

Source: FRED, Forbes

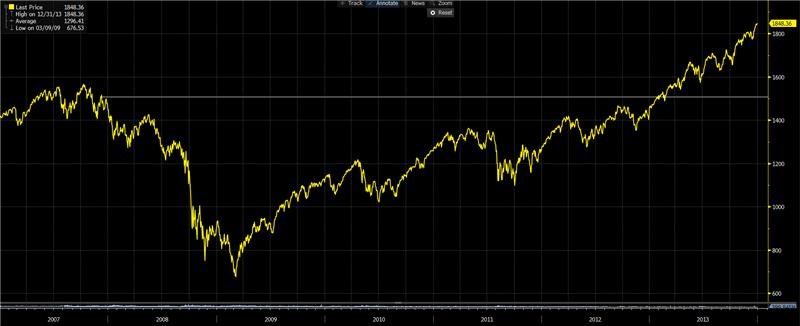

By 2013, the Fed’s balance sheet was increasing at a rate of $85 billion USD per month, reaching a total of $3 trillion USD by mid-2013. The equity market had recovered at this point, with the S&P 500 returning to pre-GFC levels by this point and continuing to break new highs.

Source: Bloomberg

All of this was on the back of a third round of asset-purchasing programs were announced, termed “QE3” but more colloquially “QE-infinity” since it was left open-ended whilst the Fed decided how and when to taper what had become a lifeline for financial markets.

Throughout the early months of 2013, no change was made to this policy, and markets remained uncertain around the future of the central bank safety net it had grown so accustomed to.

In the April 2013 Fed meeting, it had become apparent that some members were proposing the idea of making reasonable attempts to taper QE, albeit this was not public yet.

Then in May 2013, (now former) Fed Reserve Chair Ben Bernanke said at a congressional hearing that the Fed would, if it saw continued improvement in economic conditions, “take a step down in our pace of purchases”. The reaction from the market was swift, and sparked what is today known as the “Taper Tantrum”.

The Fed’s quantitative easing program represented such a massive portion of market demand, that any prospect of that demand leaving the market had a profoundly negative impact on sentiment, even if the reduction in aggregate demand was not that material.

Equities did eventually come back, and in hindsight, it’s clear that the sentiment was initially “central bank funds going into bonds should eventually go into equities”, which was later discounted by the broader market.

Reflecting on Today

Continuing to focus on the US as an example, how does our current situation compare to the environment which sparked the “taper tantrum” of 2013?

If circumstances were exactly identical, an announcement of tapering the Fed’s current asset purchase program – of which have meant the Fed’s balance sheet has exceeded $8 trillion USD this year – may trigger a sell-off in bonds and a correction in equities.

However, circumstances in financial markets are seldom identical to the past, only similar.

Today there are some key differences which may or may not reduce chances of another taper tantrum.

Communication from the Federal Reserve regarding its QE program has been clearer, with most of the market currently expecting them to announce a tapering strategy in August’s Jackson Hole symposium or their September policy meeting, according to a poll by Reuters. This is on the back of “Fedspeak”, that they expected to raise interest rates by late 2023, a shorter timeframe than was anticipated even as recently as March 2021.

The sentiment around inflation is also different, with high inflation levels expected to be transitory – with central banks the largest cheerleaders of this amongst market economists and participants – which suits the Fed’s view of easing tapering as the economy returns to healthy metrics of growth and price stability.

Tame the Taper

Although circumstances may not be identical to 2013, it is always unwise to write off potential tail-risks just because history isn’t exactly repeating itself.

The market pricing at present reflects that the Fed’s transitory inflation views are not accepted by bond markets, where US 10y “breakeven” average inflation is currently 2.2 to 2.3%, well above the Fed’s target 2% band which they forecast average inflation will fall short of.

Hence, if inflation does prove more persistent (less transitory), the Fed may need to taper sooner than they expect lest inflation overshoot their goals.

Meanwhile, we have recently seen volatility across financial markets on the back of central bank sentiment shifts towards a more hawkish stance, in both domestic and global markets.

This does not necessarily mean we will see the aggressive sell-off from 2013, but it is likely that volatility will continue as bond and equity markets attempt to price in potential changes to central bank policies over the next few years. If you do have questions around positioning your fixed-income exposure in light of potential tapering, or other tail-risks, please reach out to the team for insights and perspectives – and hope history does not repeat itself if Fed Chair Powell accidentally says something out of line in a Congressional hearing.

The views expressed in this article are the views of the stated author as at the date published and are subject to change based on markets and other conditions. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Mason Stevens is only providing general advice in providing this information. You should consider this information, along with all your other investments and strategies when assessing the appropriateness of the information to your individual circumstances. Mason Stevens and its associates and their respective directors and other staff each declare that they may hold interests in securities and/or earn fees or other benefits from transactions arising as a result of information contained in this article.