Whether ‘tis nobler in mind to suffer

The slings and arrows of higher mortgage rates,

Or to take steps against a sea of troubles,

And by opposing, switching banks to receive lower mortgage rates.”

– William Shakespeare’s Hamlet (between 1599 to 1601), adapted by Jesse Imer (2021)

I’ve written quite a few notes recently about bond markets, borrowing costs and house prices:

- Bond Auctions

- RBA policy

- House prices and CPI

- Differences between fixed and floating rate bonds

- Bond market selloff of February

All of this is meant to represent the evolving tapestry that is global capital markets, and their interactions with society.

If you have been a follower of the financial market’s narrative, then we’ve been keen commentators regarding the recent fixed-rate nominal bond selloff of Nov 2020 to Mar 2021, that has taken a breather in April and thus, received less coverage as the concern level has died down.

At Mason Stevens, we have a long history of managing fixed income – not merely commenting on the market – were we manage more than 1bio AUD of fixed income solutions for investors and our Mason Stevens Credit Fund (MSCF) has returned 8.2% in the last 12 months, despite the fixed income sell-off.

The point I wish to make today is that while fixed rate bond yields are starting to move lower, it’s likely a short term consolidation for a month or few months, but not a discontinuation of the trend higher in yields, that may resume later in the year when vaccinations are a more global story, rather than just a few specific outperformers such as the US, UK, Israel and Bhutan.

This brings me to our topic for discussion today, if now is a good time to lock-in the historically low mortgage rates available to “prime” borrowers, by paying a fixed mortgage rate, rather than a floating (variable) rate.

To cover this topic succinctly, we need to discuss 3 key criteria:

- Difference between Floating rate and Fixed rate mortgage payments

- The fixed rate forward curve

- Opportunity costs or trade-offs associated with fixing versus not

Floating Rate versus Fixed Rate

Australia is a bit of an anomaly in the world mortgage market, where about 85% of Australian residential borrowers pay floating rates of interest (source: APRA), rather than fixed.

In nations such as the USA, they pay fixed rates that are locked in from time of loan issuance to maturity, generally 30 years.

It’s for this reason that Americans may refinance their mortgage many times over the years to other providers, to seek lower borrowing costs.

In Australia, our borrowing costs have dropped over the last 20 years because market interest rates have dropped, where benchmarks such as the RBA Overnight Cash Rate (OCR) or 3-month Bank Bill Swap Rate (3m BBSW) have decreased consistently, where banks passed on their lower borrowing costs, to their underlying clients borrowing from them.

But this is a trend that may have reached its nadir, where Australian interest rates will be hard-pressed to go lower – though they may – we suggest the risks are asymmetric as there’s a greater chance they move higher, than lower.

The Yield Curve – Time-value of Money

Let’s talk about the future path of interest rates.

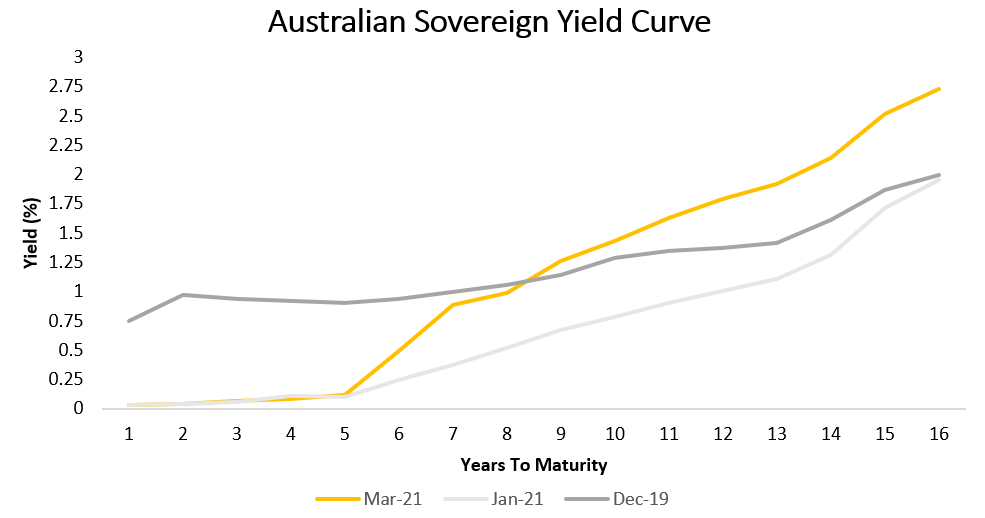

The yield curve is the market’s perception of the time value for money and uses government bond rates (“risk free rates”) as their benchmark.

The curve consists of numerous dots (bond maturities) years into the future, where there will be points in 2022, 2025, 2030, 2040 etc. These dot points can be joined to graph a yield curve that represents a forward-looking estimate for money’s value – or purchasing power.

What the yield curve – and hence, the market – is telling us right now is that the probability-weighted outcome is for interest rates (bond yields) to rise.

And not just by a little, by 1% or more, which will increase your annual mortgage cost by this margin.

Bringing this back to residential home loans: this suggest that some of the low rates available today, may not be available in months to come as banks increase their mortgage rates to reflect the higher market funding costs (bond yields) and those paying floating or variable rates of interest – 85% of home borrowers – will begin to see higher rates of payment required to service their loans.

Opportunity Costs and Trade-offs of Fixing Rates

Opportunity cost is the difference in cashflow, or valuation associated with one investment decision versus another.

As an example:

- 1mio home loan

- 30-year term

- Variable interest rate, typically 3m BBSW + 2%, where,

- 3m BBSW = 0.02% and

- Variable mortgage rates are therefore ~2.02%.

- Current borrowing cost is $20,200/year, assuming no other associated costs

- If variable rates increase by 1% over the next two years, your new borrowing cost is $30,200 (49% higher).

The suggestion to fix part or all of a mortgage is a very personal decision. It matters on your personal credit worthiness (score), the banking institutions that you have relationships with, the flexibility you require if ever needing to amend loan terms, and the possibility of ever needing to exit the loan (or re-finance it elsewhere) and associated “break” costs.

For these reasons this note has a certain generality, where the specifics should be analysed yourself, or with your financial advisor or banker.

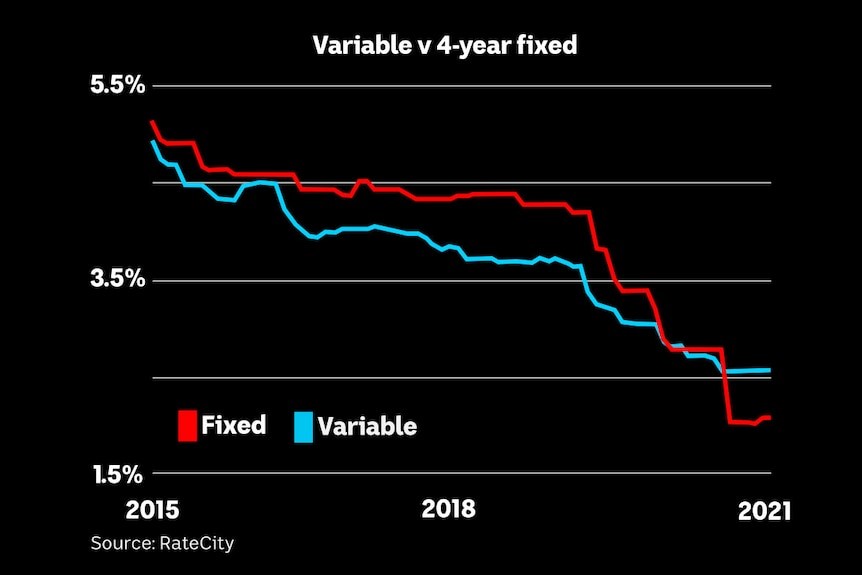

However, there is a market opportunity where fixed-rate loans can be lower rates than floating rates, but also, the 2, 3, 4 and 5 year fixed-rate terms have lower rates, that may be locked in to stabilise mortgage costs.

Take for example the latest rate card from RateCity;

Cheapest mortgage rates:

| Term | Rate % |

| 1-year | 1.69 |

| 2-year | 1.74 |

| 3-year | 1.75 |

| 4-year | 1.89 |

| 5-year | 2.14 |

| Variable | 1.77 |

Several of the fixed-rate loans are less than 2% p.a., quite a favourable borrowing cost for an asset that in Australia, traditionally has returned a much higher rate of return.

Combining the Elements

Therefore, if we combine the elements we’ve discussed so far, not only can we effectively hedge our interest rate risk of higher variable interest rates by partially or fully hedging our mortgage cost now, but we may do so at little to no accounting cost, where 2 or 3 year rates are slightly below variable rates, thus achieving a lower rate by fixing.

Moreover, you would also be making the optimising decision to hedge the possibility of higher interest rates, should floating rates rise over the coming years.

However, there is a risk that you may miss out on lower interest rates should variable rates decline even further, or that fixed rates might move slightly lower before moving higher, but we would consider that the risks are skewed to higher mortgage rates than lower rates.

Lastly, we reiterate the consistent message from the RBA, where they formally provided monetary policy transparency by putting in place their 3-year government bond yield target of 0.10% from March 2020 to ~March 2023. That’s a little less than 2 years away, if not extended.

This is why the market is starting to price higher rates, as this grace period is ending.

The views expressed in this article are the views of the stated author as at the date published and are subject to change based on markets and other conditions. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Mason Stevens is only providing general advice in providing this information. You should consider this information, along with all your other investments and strategies when assessing the appropriateness of the information to your individual circumstances. Mason Stevens and its associates and their respective directors and other staff each declare that they may hold interests in securities and/or earn fees or other benefits from transactions arising as a result of information contained in this article.