Have you ever wondered why we have a term for Auctioneers that “cry”, meaning to speak, shout or sing loudly as a proclamation?

The origin of the term crying followed a time when Roman soldiers would thrust spears into the ground to signal the start of the sale of auctions for the dispersal of spoils of war.

Another early term for an Auctioneer was an “Out Crier” or “Town Crier”, whose origin was derived from Spartan Runners in the early Greek Empire, later taken up by the British empire where Town Criers were protected by law as the spokesmen for the King.

This is why “don’t shoot the messenger” has a very literal meaning, as any harm done to the Town Crier was punished as if it was treason.

Because of this rich history regarding auctions, to this day, bond auctions, antique auctions, property auctions hold a significance within society with certain formalities that imbue the process.

Bond Auctions

Bond auctions are a relatively unknown part of finance, where the outcomes have wide ranging implications for government funding costs, equity valuations, taxation and asset allocation.

The high-level process is quite simple.

A government issues an Announcement that they will be issuing debt in the near-term.

For example, the Australian office of Financial Management (AOFM) does this here.

The government agency provides specific details prior to the auction, such as:

- Auction date

- Settlement date

- Maturity date of the security

- Security being offered (new or a “tap” of an existing security)

- Bid opening and closing time

- Terms and conditions or other pertinent information

Bidding is the next step in the process, where bids can only be placed into the tender through authorised representatives.

These are nearly all large global banks – such as ANZ, Bank of America, HSBC, Deutsche, Morgan Stanley, NAB, Nomura, UBS, etc. If you’re interested in what banks are “intermediaries” in the Australian process, a comprehensive list can be found here.

What this part of the process means is that access to primary bond auctions is restricted to those with wholesale access to financial markets, i.e. those with a sophisticated level of financial knowledge around government bond yields, international finance, and institutional trading and investment relationships.

Continuing our AOFM example, there are 15-20 authorised intermediaries for bond auctions, and while these banks may be bidding on behalf of their non-bank clients (such as Australian superannuation funds, smaller commercial banks, World Bank, global central banks, sovereign wealth funds etc.), there is only a limited range of participation in the tender and auction process.

The final step in the process is Issuance, where the Treasury or Debt Management Office (DMO) issuing the securities will inform bidders if they were successful in the auction, confirming the payment amounts so that settlement can occur.

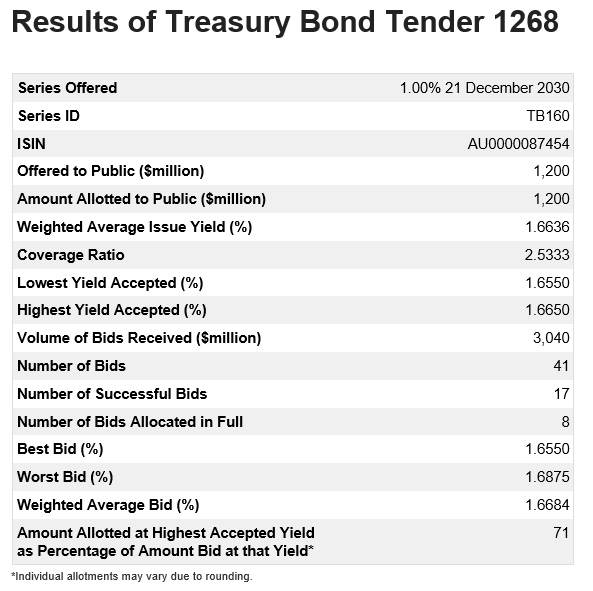

The output to this looks like this, a recent issue of 1.2bio AUD of 10y Australian Commonwealth government bonds:

Source: AOFM

US 7y Bond Auction

In February, the US Treasury sought to issue about 60bio USD of 7y government bonds via their regular auction, a transaction that was Announced ahead of time and would generally be well received by investors (bond buyers).

However, the transaction did not go well, with markedly decreased participation by bond buyers which had little appetite for the issue.

As the market was wary of the recent sell-off in government bonds, investors did not want to bid into a potential deal that could immediately lose them money.

The news of the decreased demand for US Treasuries via the auction programme spooked financial markets that week, which saw a further sell off in US Treasuries (yields higher, prices lower), and elicited further fears of ability for financial markets to consume the increasing debt issuance from government deficit spending.

Decreased Bid/Cover

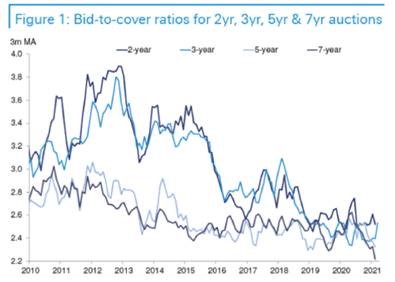

I read some recent research by Deutsche Bank that highlights bid/cover ratios have been declining for years, as auction sizes have increased (issuing more debt), where the quantum of investors buying bonds hasn’t increased nearly as much.

Hence, we get less bids relative to the auction size – a lower bid/cover ratio.

Source: Deutsche Bank

More Debt to Come

There’s certainly going to be more and more debt to come.

The US has recently passed a 1.9trn USD stimulus package, issuing more debt yet again, with President Biden proposing the Administration’s “Build Back Better” plan of another 1-2trn USD of “hard” infrastructure spending (building physical assets) and outlining yet another “soft” infrastructure package yet to come, regarding healthcare and disability spending of another 1-2trn.

While part of this is expected to be funded by increasing corporate taxes – and only if the Administration is able to pass the legislation – it’s assumed that part of it will pass through Budget Reconciliation process, where the US will be issuing an ever-increasing volume of government debt via auctions.

Also, the corporate tax collection is forecast to take over 10-15 years to fund PART of the projects, where the spending will be financed by debt issuance in the interim period.

It’s at this point that I can’t help but wonder what happens when Treasury auction sizes double, say from 60 to 120 billion USD per auction, and without a material rise in yields (higher), the bid/cover ratios continue to drop yet again.

Likely, government bond yields would rise under this scenario to create a new “market clearing price”, establishing a new equilibrium value for transactions to occur between bond buyers and sellers.

Flow-on Effects

This has several second order effects that will impact other financial markets.

Firstly, we’ve seen how the market reacted in February due to the poor turnout in a 7y US Treasury auction. We could expect similar reactions if this happens again, likely increasing asset price volatility.

Secondly, higher bond yields will provide further fodder for investors to re-consider their sensitivities to interest rate duration – those assets with weighted average cashflows to be received further into the future. Common examples of these are equities with higher P/E ratios, where the earnings are forecast to be exponentially higher in the future – and unknown element – while the value will be eroded by higher opportunity costs in simply buying government bonds at higher yields.

A simple thought experiment for this:

If you had bought Amazon in 1999, it would’ve taken you ~10 years to break-even on your investment, given the low growth in the stock price after the “Tech Bubble” wipe-out.

That begs the question, would marginal investors in US equities – even success stories such as Amazon – have invested in higher-risk equities if they had been able to achieve “risk-free” returns buying US government bonds at 5% p.a.?

Would many companies that are successful today have achieved their stellar returns, if investors had been able to make comfortable returns buying government bonds with less risk?

Lastly, this concept is known as the “crowding out” effect, where a growing deluge of debt issuance will see higher government bond yields, which will cause markets to re-price other asset classes such as credit bonds, equities, infrastructure, property, etc. This can make it harder for other asset classes – other forms of corporate finance – to be crowded out by the government, where they have to increase the yield on their investments to compete with government bonds.

Closing Remarks

Western nations have enjoyed the privilege of issuing larger volumes of government debt over the years, in an environment where yields have moved lower and lower.

This debt volume is starting to matter – as the younger generations realise, they may ultimately have to service the debt they’re inheriting from older generations.

For these reasons, US Treasury auctions are on our minds, where we watch with keen interest in the market’s ability to digest the growing auctions, aware that there may be volatility as well as investment opportunities should there be signs of indigestion.

In 1789, Thomas Jefferson wrote to James Madison about this very subject, a forward-thinking individual of obvious intellectual foresight.

If you’re interested, Princeton University has a large selection of these notes that are well worth a read.

In particular in Volume 15, 27 March to 30 November 1789, Jefferson wrote:

“Then no generations can contract debts greater than may be paid during the course of its own existence”.

This concept will regain popularity and auctions will remain a key point of interest, as they have for centuries and millennia already.

The views expressed in this article are the views of the stated author as at the date published and are subject to change based on markets and other conditions. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Mason Stevens is only providing general advice in providing this information. You should consider this information, along with all your other investments and strategies when assessing the appropriateness of the information to your individual circumstances. Mason Stevens and its associates and their respective directors and other staff each declare that they may hold interests in securities and/or earn fees or other benefits from transactions arising as a result of information contained in this article.