Government debt issuance is generally a fairly benign topic of discussion or conversation, we know this, where we’re all aware of this metaphorical anchor and the drag it has on economic growth.

If debt allows a borrower to bring future consumption forward (from the future), then there is a point of repayment or debt amortisation that slows down future growth.

That is where we are at right now – we are aware of this – but what we are not actively talking about is what we can do about it!

And I’m not talking about debt monetisation, that we’ve written about ad nauseum in our morning note series with our latest missive published last Monday, exploring the concepts of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and how the US government is justifying ongoing deficit spending.

We are talking about a political and governance issue, where as a nation, we should extend our debt maturity profile if we’re honestly not going to pay it off.

Where if we aren’t going to practice austerity and look to pay down our outstanding government debt, then we should make our best efforts to lower the long-term burden on Australian taxpayers, who are funding the deficit spending.

Future Deficits and Debt

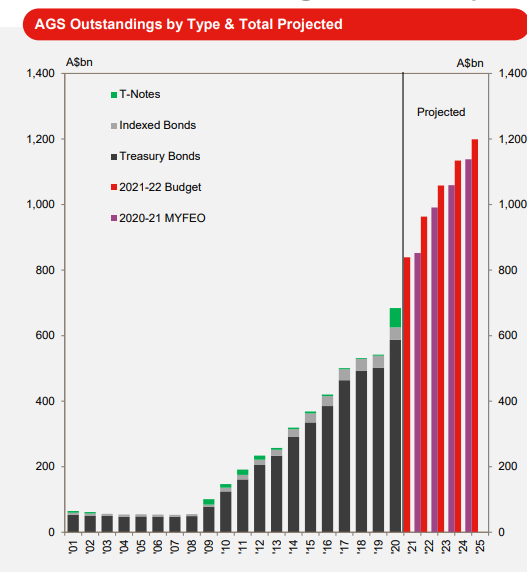

In our 2021 Commonwealth government budget commentary, we wrote about how we don’t have a budget surplus – where costs are LESS than income – projected until 2031/32 financial year, ten years away.

Under this forecast, our gross government debt will total over 1 trillion AUD in the coming years, moving towards 1.2 trillion AUD by 2025, not far away.

Source: Westpac

This, during a time of likely low economic growth as the nation psychologically recovers from the pandemic, new businesses are established and slowly gain traction and market share.

Hence, our debt burden is growing, and we’re expecting higher interest rates (funding costs) as well.

This is a lose-lose scenario for Australian taxpayers, whose tax receipts are factored into Commonwealth budget forecasts, as “debt servicing”, or interest payments.

Not a New Concept

This is not a new concept either, where I wrote about this on 19 June 2019, in a note titled “How Low Can You Go?”

At the time the market was forecasting a decline in the RBA Overnight Cash Rate (OCR) from 1.5% – now currently at 0.10% in July 2021 – and we only had 540 billion AUD of government debt outstanding (those were the days!).

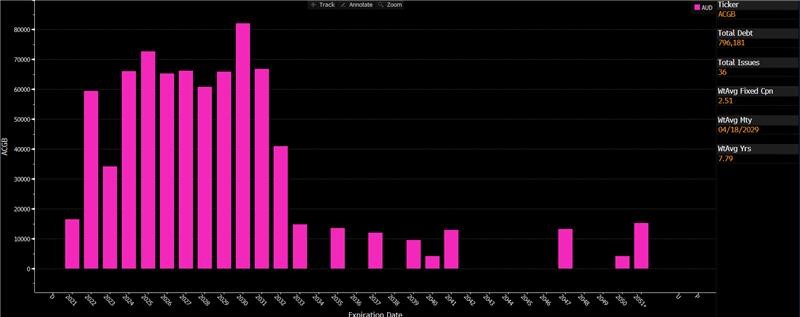

Today, we have 796.1 billion AUD of government debt outstanding, across the below maturity profile.

Notice that the bulk of the debt is maturing within 10 years from now, with very little maturing after 2035?

The weighted average maturity of our Commonwealth government debt is 7.79 years.

That is a weakness that the Australian taxpayers may have to bear the burden of if interest rates rise.

Source: Bloomberg

Even then, with HIGHER interest rates, it made sense to extend Australia’s debt profile, as even with our government surpluses forecast – we weren’t going to run surpluses to make a material repayment of the government’s debt outstanding.

Logic Behind Long-term Debt Issuance

There are three key arguments for why long term debt issuance is positive for Australian taxpayers – certainly more relevant within 12 months of our next Federal election.

- We lock in low interest rates where yields are near all-time lows

- We match the maturity profile of our assets with our liabilities (debt/bonds)

- Locking in low rates can be self-validating

Let’s assess.

1. Locking in Low Funding Costs

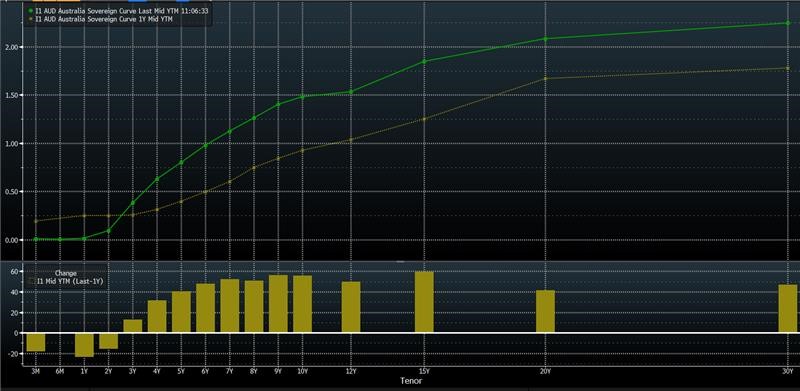

I think most of us are aware that interest rates are near all-time lows and there’s an asymmetric profile of scenarios ahead of us, where there’s limited ability for interest rates to move lower – confined by 0% as a barrier, with unlimited upside potential for interest rates (funding costs) to move higher.

If we look at the yield curve as a depiction of funding costs into the future (green line), we can see that the government can issue 10-year debt at or around 1.5%, but more importantly, can issue 20-year debt at 2% or 30-year debt at 2.25%.

Source: Bloomberg

But I argue this isn’t far enough, as we should also be considering issuing for 30+ years, possibly 40-50 towards 100 years.

2. Asset/Liability Matching

This argument is derived from an old axiom of financial theory – you maximise efficiency and minimise cost by matching the duration of assets and liabilities.

This can be an in-depth topic so I will keep it short: a long yielding 50-year government bond (say at a yield below 3.5%) may be an ideal way to fund a bridge, port, railyard, space hub – rather than a 10-year bond/loan that will need to be re-financed (rolled) 5-10 times over the life of the asset.

This can also be seen as prudent financial management, where every time the bond or loan is re-financed, the government runs significant re-funding or re-financing risk, linking in with point #1.

3. Self-validating Low Debt Costs

Selling long term debt can be seen as a directional bet on markets – that you are hedging the risk of higher interest rates by locking in lower costs today, for a significant share of government debt.

I would argue that it is in taxpayer’s best interest to lock in fixed costs for interest outlays as this can allow for more forward thinking and stable tax policy.

As we wrote about in April, we are worried about the sheer amount of debt being issued into markets, where unless central banks continue (or increase) their asset purchase programs, there may not be enough buyers of bonds at current yields – where bond buyers may seek higher yields as compensation for more allocation to bonds, or inflation risks.

Countries That Have Issued Long-Term Debt

In this regard, Australia is well behind other governments when it comes to issuing long-term government debt, where there’s a whole range of sovereigns that have issued 50-100 year debt in recent years.

For example

50-year bonds:

- Canada at 3.0%

- Italy at 2.9%

- UK at 2.6%

- France at 1.9%

- Czech Republic at 2.7%

- Switzerland at 2.0%

100-year bonds:

- Mexico at 4.2%, and issued in euros not Mexican pesos

- Ireland 2.4%

- Belgium 2.3%

- Peru 3.3%

Closing Remarks

It’s never a bad time to have a conversation about lowering the debt servicing costs of an entity – whether it’s a household, a business or a Federal government.

And if we aren’t going to materially reduce our debt burden in the coming years, then we should adopt an approach that lowers the required taxation from workers and businesses to fund the current and future deficit spending.

I brought this up while working for a previous employer, attending an AOFM function in 2019, and was told that AOFM had considered long-term debt issuance – given other nations such as Austria, France, Canada, UK, Italy, Ireland, Mexico etc were all issuing long-tenor debt at the time – but had considered that these bonds might not be actively traded enough with similar liquidity to existing bonds that trade in secondary markets.

This is a rather weak answer, as the demand for long-term bonds is well established from sovereign wealth funds, other central banks, life insurers and superannuation (pension) funds.

Also, there are typically buy-and-hold investors, who aren’t seeking to actively trade their fixed income holdings, they’re looking to asset/liability match, as is our point #2.

Hopefully this won’t be a missed opportunity when I write another iteration of this note in 2023, as it has been these last two years.

The views expressed in this article are the views of the stated author as at the date published and are subject to change based on markets and other conditions. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Mason Stevens is only providing general advice in providing this information. You should consider this information, along with all your other investments and strategies when assessing the appropriateness of the information to your individual circumstances. Mason Stevens and its associates and their respective directors and other staff each declare that they may hold interests in securities and/or earn fees or other benefits from transactions arising as a result of information contained in this article.