It hasn’t been all that long since the last Federal Budget, having been produced late last year due to COVID, published in October 2020 instead of May.

With that in mind, we wouldn’t have expected too much to have changed in the ~6-7 month period, but also with the expectations that the Budget would remain expansionary and likely be populist. Given we’re within 12 months of an election, we expected the budget to provide short-term benefits to Australians to increase the incumbent government’s chances of re-election.

We got what we expected.

In keeping with the template we established last year, in today’s note we won’t belabour the specific policies contained within the 386 page document, as you’ve likely already read them through various media outlets such as the ABC, SMH, 9News and other publications.

Instead, we will analyse the following topics, which directly reference the financial market implications the Budget has:

- Key policy initiatives

- Budget funding

- Australia’s credit rating

- Yield Curve

- Cross-market correlations

- AUD/USD currency

- Monetary policy implications

Summary Position

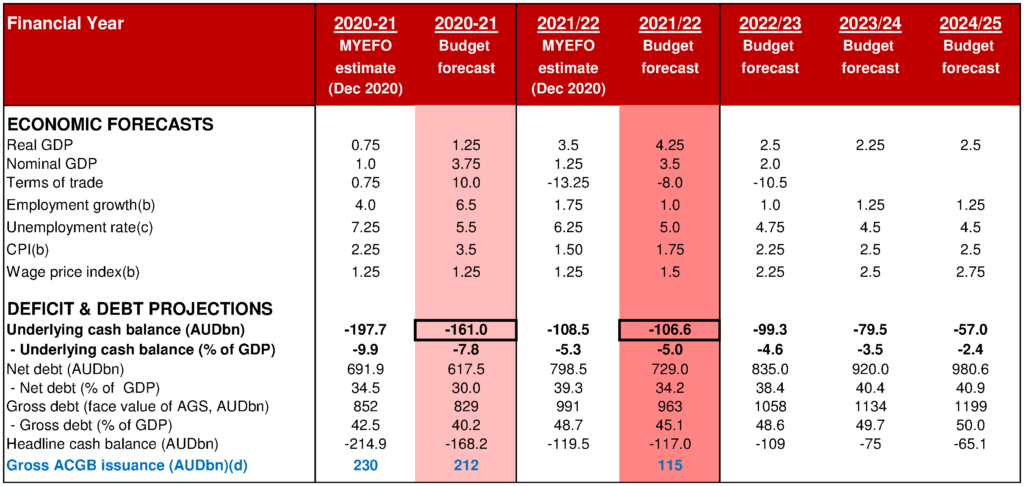

The Budget that was produced last year was noted to have quite conservative estimates, that was always going to surprise to the upside. It’s for this reason that the “surprise” windfall was expected but was also seen by looking at monthly budget statements.

For example, iron ore related revenues were calculated with a $55 USD per tonne spot price, where the spot price has been 3-4x this.

The cash deficit for 2020/21 was revised almost 40 billion lower to 161 billion (7.8% of GDP), from 213.7 (11%).

Budget deficits are forecast all the way to 2031/2032, which will surprise many fiscal conservatives given the current government has run elections on deficit reduction stances.

Gross debt is expected to be 829 billion (40.2% of GDP) this financial year, and stabilising around 51% of GDP in the coming years.

If we remember back to 2013, it was the Coalition that actively campaigned against Treasurer Wayne Swan’s 10% debt/GDP ratio as a “budget emergency”, where we’re now at 4x higher levels and not seeking any austerity measures to ameliorate the situation.

The government anticipates spending around 70% of the improved position, due to the sharper recovery and higher commodity prices.

For example, 4-year forward looking revenues have improved 122 billion AUD, where the government is projecting to spend 88 billion of this.

Key Policy Initiatives

- 17.7 billion to improve aged care, a response to the Royal Commission, that will include another 80,000 new home care packages, increased nurses and carers; 33,000 new training places for personal carers and $10/per resident per day to assist viability and sustainability of the sector.

- We’re encouraging research and development (R&D) by creating a “patent box”, which establishes a 17% tax rate for income derived from Australian medical and biotech patents, encouraging business to conduct research here due to the tax incentive.

- Additional 1.9 billion to assist the current lacklustre vaccine rollout.

- Full expensing and loss carry back for businesses, extended to 2023.

- Extending the low and middle income tax offset (LMITO) for a further year until 2022, which provides higher post-tax income to ~10.2 million Australians, worth up to $1080 for individuals or $2160 for dual income couples.

- 4.7 billion to improve women’s safety, economic security, health and wellbeing. The allocation provides 1.1 billion for women’s safety, 1.9 billion for women’s economic security and 1.7 billion for improving childcare affordability. I can’t help but feel it’s strange that at a Federal level we view childcare as solely a women’s prerogative, rather than classifying this expenditure as “family assistance”.

Budget Funding

If we have a $106.6 billion AUD deficit (5% of GDP), then we have to fund this expenditure, and this will be principally done via increased bond issuance, rather than asset sales.

The Australian Office of Financial Management (AOFM), our national debt management office, has announced they will require 130 billion of funding in 2021/22 financial year, also accounting for bond maturities between now and 30 June 2022.

This is a revision downwards from last year’s Budget projection by 37 billion and wasn’t a surprise to bond market aficionados as AOFM had already been issuing less in previous weeks, which was interpreted as an informal expectation of lower rates of funding to come.

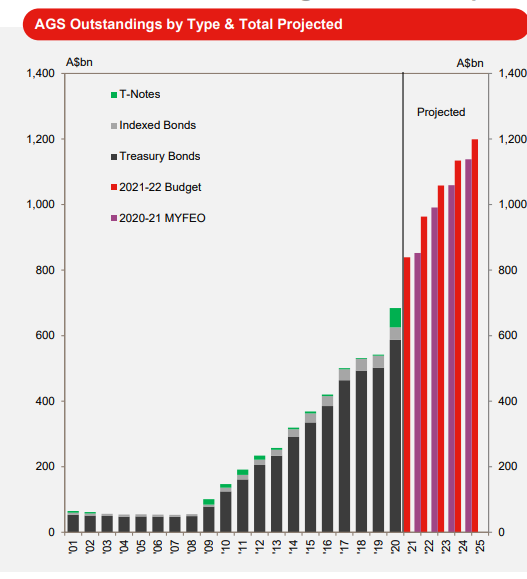

However, our government debt is still growing at an enhanced rate, denoted by the below chart.

Will Australia become Australi?

Whenever Australia runs higher deficits and expands the government’s gross or net debt, there are always questions about the viability of our AAA sovereign credit rating, which if lowered, would also increase the cost of funding of corporate bond issuers, and likely see a credit rating decrease in NAB, CBA, WBC and ANZ to boot.

Since the Budget, two of the big three credit rating agencies – Standards and Poors (S&P) and Fitch – have updated their outlooks, opting to keep Australia’s rating on “negative” outlook, meaning it could be downgraded to AA+ (a lower rating) in the coming months or years.

Fitch said the negative outlook reflects uncertainties around the medium-term debt outlook, which is destined to hit 1 trillion AUD in 2022/23 financial year.

Yield Curve

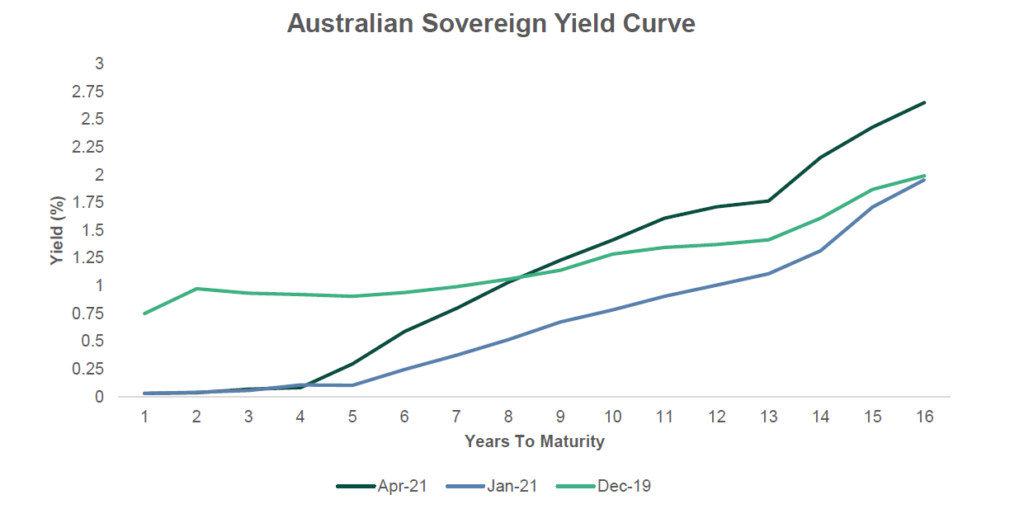

Given the scale of the forward deficit profile and that infrastructure remains a Budget focus, there is likely to be ongoing steepening pressure on the Australian yield curve, especially for 10 to 30 year government bonds.

This steepening pressure is partially offset by decreased long tenor issuance, and likely to be well-received by the market where there’s increased demand for Australian government bonds because they have a AAA rating and have relatively high yields compared to similar AAA bonds (i.e. German Bunds at negative yields).

Cross-Market

Australia remains attractive on the global scale on a “reward for risk” basis, versus many (other) global markets, where nothing in the Budget should alter this fact.

This is certainly the case for the reasons mentioned above in our yield curve notes but is also relevant when analysing Australian equities versus global alternatives.

In the case of the ASX 200 versus the S&P 500, the ASX could be preferred on many measures, where our median P/E ratio of 19.3x offers compelling value compared to the USA’s 22x.

AUD/USD Currency

The Budget should also not change our view on currency, where the AUD remains undervalued when viewed through both commodity and interest rate differential lenses, despite the rising political tensions with China.

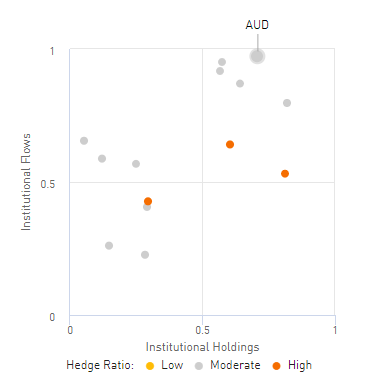

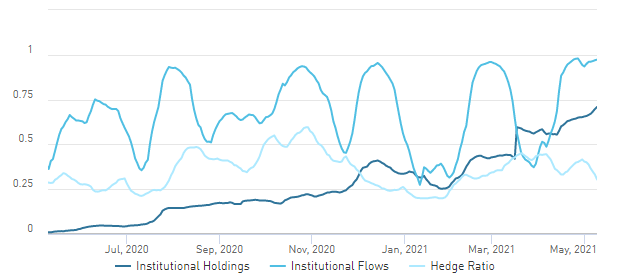

Our AUD has been supported by large institutional fund manager flows, which has had a positive impact, as global asset allocators are bullish the AUD with respect to the USD, because of the commodity and reflation narrative.

This puts AUD at the top of State Street’s institutional FX flows chart:

And also in a clear uptrend in both holdings and flows:

Monetary Policy Implications

The expansionary budget that sort-of looks at infrastructure and productivity enhancements should be welcomed by the RBA, who have been seeking Commonwealth and State balance sheet assistance for the past 2-3 years, to increase spending and assist the RBA in achieving their second mandate of maximum employment.

However, the RBA won’t materially alter their forward guidance for the Overnight Cash Rate (OCR) as the spending is temporary, and they have explicitly stated that we won’t achieve sustained (the key word) inflation until wages rise when full employment is realised.

Hence, the RBA will view the increase in government expenditure and increased aggregate demand as temporary.

As another segment of monetary policy, it’s likely that the lower AOFM debt issuance task will result in a tapering of the RBA’s bond purchase program, where if continued at the current rate, would be purchasing a relatively higher portion of government debt per week.

This is why we would expect the RBA to extend their QE program further and avoid the expectation of them hiking interest rates sooner than other global central banks – which would likely see the AUD appreciate and in-turn make Australian industry less competitive – instead they will extend the QE but taper it to a lesser amount that still results in a similar monetary accommodation.

Closing Remarks

The spectre haunting the entire Budget is Australia’s ability to vaccinate the majority of Australians, and the assumptions surrounding the vaccination progress.

In the October 2020 Budget, it was assumed vaccination would be “fully in place by late 2021”.

However, in this update, the words changed to “likely to be in place by the end of 2021”.

This is the Treasury hedging their bets that the vaccination rate continues at the slow rate, where the government continually revises their target vaccinations lower, and recently abandoning a vaccination target all together, as a face-saving measure.

The Budget papers also assume that our international borders will remain closed until mid 2022, with “small phased programs” to be brought in to return international students back to the Australian education market, as universities haemorrhage billions of dollars of losses.

The government adopted some of the Royal Commission’s recommendations into age care, such as 200 minutes of direct contact hours per day per resident and more nurses but did nothing to add compulsory training for aged care workers or producing a transparent framework on complaints and abuse. As for the funding, the 17.7 billion AUD has been calculated to train ~34,000 people and this includes those already working within aged care. Therefore, it’s hard to understand how we will meet the estimated 1 million aged care workers required by 2050, without massive spending in the years to come.

Therefore, expect more spending to come.

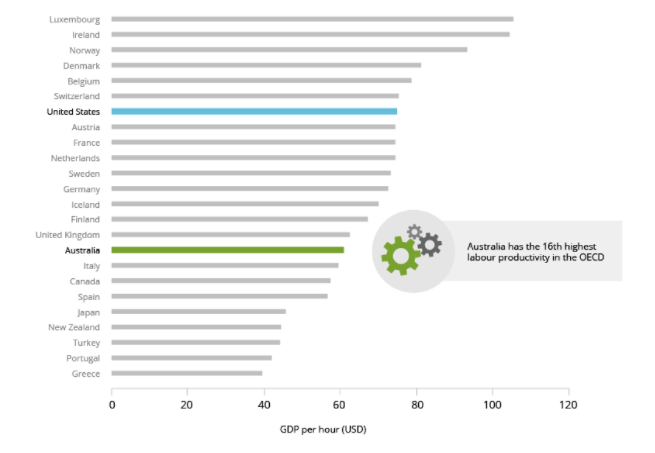

Lastly, the Budget again lacked meaningful impact in productivity enhancement, where Australia is decreasing on the world scale:

Productivity reform and spending would’ve been a welcome development to address the increase in our government debt levels, and grow our way out of the pandemic, rather than spending our way out.

In this regard, we return to our original premise where this Budget was going to be populist and full of short-term stimulatory impacts for the economy, rather than long-term reform and productivity enhancement.

Maybe next year.

The views expressed in this article are the views of the stated author as at the date published and are subject to change based on markets and other conditions. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Mason Stevens is only providing general advice in providing this information. You should consider this information, along with all your other investments and strategies when assessing the appropriateness of the information to your individual circumstances. Mason Stevens and its associates and their respective directors and other staff each declare that they may hold interests in securities and/or earn fees or other benefits from transactions arising as a result of information contained in this article.