After last week’s Federal Budget, we flagged that the risks are growing that Australia may be downgraded from AAA to an AA+ credit rating, having already been provisioned with a “negative” outlook over the last few years. A negative outlook indicates the agencies have flagged it for downgrade.

This election-year Budget forecasts more continued budget deficits for the coming years until 2031/2032 fiscal year, a change in rhetoric where we used to espouse fiscally conservative and “balance budget” policies.

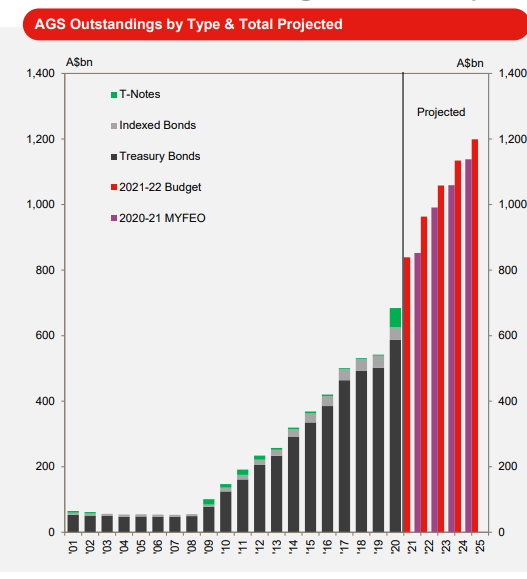

While the cash deficit for 2020/21 was revised lower by 40 billion AUD, from 213.7 billion AUD (11% of GDP) to 161 billion (7.8% of GDP), debt issuance is still ballooning where Australia will have more than 1 trillion AUD of debt outstanding in the not so distant future.

This is relevant as rating agencies were accommodative to maintain Australia’s AAA rating in the 2010-2020 period, where the incumbent governments ran for office on fiscal conservatism platforms. The 2013 10% debt to GDP ratio was described as a “Budget emergency”.

Our government debt to GDP ratio is now 300-400% higher than the 2013 level, and with cash deficits forecast 10 years into the future, we’re transparently stating that we aren’t seeking to reduce spending any time soon and hence, increasingly likely to lose our sterling AAA rating.

The below chart shows current and projected Australian Government Securities (AGS), forecast by Australia’s debt management office, the Australian Office of Financial Management (AOFM):

Will We Lose Our AAA?

Rating agencies have been able to look past the once-off fiscal expenditure due to the COVID-19 pandemic, where all AAA-rated nations with the exception of Canada have retained their AAA rating.

However, in Australia’s case we’ve now transitioned from once-off spending to persistent spending and on-going budget deficits for the next 10 years; rating agencies will need to assess whether the current rating reflects Australia’s forward-looking financial position.

Of interest, we’ve read some commentators arguing that this Federal Budget is in breach of the Charter of Budget Honesty, which commits our government to “achieving budget surpluses, on average, over the economic cycle”.

On face value, this has been viewed quite negatively by Standard and Poors (S&P), the largest credit rating agency by market share.

Elements of a Credit Rating

Credit ratings are an assessment of two major factors:

- Probability of default

- Probability of loss

These might sound the same, but probability of default is a calculation of a borrower’s capacity to repay a loan at maturity, while probability of loss is an assessment of a borrower’s ability to service a loan (make interest payments) as well as repay the loan at maturity.

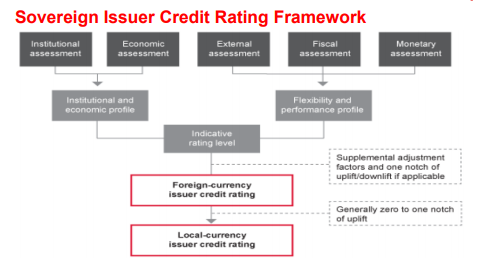

To use S&P’s approach, they calculate this probability using the five following criteria:

- Institutional governance effectiveness

- Economic structure and growth prospects

- External liquidity and international investment position

- Fiscal performance and flexibility and debt burden

- Monetary policy flexibility

These factors will then feed into two credit ratings, a foreign currency rating and a local currency rating.

This happens when a government issues debt in a currency other than its own i.e. the Australian government issues in USD, EUR, GBP, CNH, JPY etc (foreign currency) instead of AUD (local currency). A government has less ability to service foreign currency debts due to less flexibility in navigating the FX risks.

Implications for Other Debt Markets

Our sovereign credit rating also has implications for all debt issuers that are deemed to have sovereign support, where if the sovereign is downgraded, often the benefactors of sovereign support are also downgraded.

This is the case for Australian government agencies such as Export Finance Australia (EFIC), or Australian Rail Track Corporation (ARTC), but also true for ANZ, NAB, CBA, WBC and Macquarie, the five banks in Australia deemed to have implied government support (a legacy of both the Rudd government in 2007/2008, but then later reaffirmed by the Turnbull government).

This is quite important as a decrease in Australia’s sovereign rating could see a downgrade to our major banks as well, potentially increasing their borrowing costs and making them less competitive relative to international peers.

On the flip side, this would possibly help Australian banking competition too, where the majority of Australian banking institutions do not receive this sovereign support and credit rating uplift, where their borrowing costs are higher because of this. A downgrade to the major banks would be a levelling of the domestic playing field, allowing the likes of Bank of QLD, Bendigo Bank, Credit Union Australia and many more to compete more closely on net interest margins (NIM).

What’s Priced In?

A simple way to review what the institutional market has priced in is to compare Credit Default Swaps (CDS), a credit derivative linked to the probability of default of a specific bond issuer.

In the below assessment, we compare Australia (AAA) CDS versus France and Japan CDS (both AA).

In reality, Australia’s 5y CDS priced at 0.62% sits in between Japan’s at 0.82% and France’s at 0.24%, highlighting that the market has already priced in the possibility of a sovereign credit rating downgrade.

What are the Rating Agencies Saying?

After the Federal Budget, S&P issued a statement (emphasis ours):

“The negative outlook on Australia reflects a substantial deterioration of fiscal headroom at the AAA rating level and our view that risks remain titled toward the downside. For example, medium-term fiscal consolidation at the general government level, which includes subnational governments, could take longer than we currently expect. The federal government has signalled that it will not prioritise budget repair until unemployment – currently at 5.6% – falls below the pre-pandemic level of about 5.1%. This is a shift from the 6% target that it introduced in 2020.”

Whereas Fitch, the 3rd largest credit rating agency by market cap issued their statement the following day (again emphasis ours):

“When we affirmed the rating in February 2021, with a Negative Outlook, we projected that general government gross debt/GDP would peak in the fiscal year ending June 2023 (FY23) and then decline. The budget’s forecasts, whose assumptions we view as credible, are broadly consistent with this trend. Moreover, the marked improvement in the fiscal performance in FY21 has resulted in a stronger outcome than we had assumed, meaning that the debt trajectory will start and peak at a lower level than we had anticipated.”

“We believe there is potential for the public finances to overperform relative to the budget’s projections, given its relatively conservative assumptions for iron ore prices and employment. Moreover, once the government has achieved its targets under the first phase of its fiscal strategy, of bringing unemployment back below pre-pandemic levels of around 5% in FY23 and ensuring the economic recovery is secure, we anticipate that it will turn its focus to fiscal consolidation (“budget repair”), which is not reflected in the budget’s current forecasts.”

“The Negative Outlook on Australia’s rating reflects in part uncertainties around the medium-term growth trajectory, which are pertinent to the rating – given Australia’s high general government debt/GDP relative to ‘AAA’ peers”.

Closing Remarks

Fitch’s comments are a great summary, and we think accurately reflects that the Federal Budget was set using conservative assumptions, which may lead to budget upgrades in the future.

Whether this is sufficient to stave off a downgrade will come down to subjective assessments with regards to the agency’s credit rating methodology, and their own forecasts for the budgetary position.

In our view, the biggest factor affecting the risk of rating downgrade is whether the agencies believe the political considerations for budget deficits are appropriate, or if the government is merely enacting a populist budget.

If they view the latter, a downgrade is almost certain, whereas if they believe the politics warrant an expansionary budget and that future budgets will benefit from this year’s spending, a downgrade is less likely.

The views expressed in this article are the views of the stated author as at the date published and are subject to change based on markets and other conditions. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Mason Stevens is only providing general advice in providing this information. You should consider this information, along with all your other investments and strategies when assessing the appropriateness of the information to your individual circumstances. Mason Stevens and its associates and their respective directors and other staff each declare that they may hold interests in securities and/or earn fees or other benefits from transactions arising as a result of information contained in this article.