I’m a large fan of reading central bank academic discussion papers as they’re a key insight and provider of investment edge.

What I mean by this is that because academic journals are inaccessible to a large part of the public, often as difficult to read as Miguel de Cervantes 1605 literary classic “Don Quixote”, a lot of people simply don’t read them, despite knowing they may have insights that could add value.

Connecting the dots over this past 24 months, we’ve come to realise that most central banks are employing similar communication strategies as their method to inform the world of their likely actions, before they enact them, called “forward guidance”.

The RBA even went so far as to produce an academic discussion paper detailing how they craft their own publications based on their:

- intended audience,

- readability of documents, and the

- amount of reasoning within those documents.

What these central banks are doing is:

#1 Release an academic paper discussing the policy initiative and likely effects

#2 Publish articles about possible policy using friendly sources to the Bank, i.e., for the RBA they may use the AFR or The Australian newspaper

#3 Bank employees and speakers will reinforce these views when speaking at conferences and events

#4 Assess the reaction of the market to #1-3 and if no significant fallout, look to move ahead with the proposed policy – likely giving a few weeks or months of warning

The RBA have done this several times this year through their March 2021 publication of a tightening in financial conditions, or their September 2021 publication on inflation’s relationship with unemployment – as two examples that we’ve covered in detail.

It was therefore quite a surprise to me when last week, the US Federal Reserve Bank broke with recent convention and published an article that deviated with recent ideology, which has made me question how homogenous the thought-base of the Fed is, and how convicted they are in their forward guidance.

A Non-Standard Paper

On the 24th of September, the Federal Reserve published the article written by senior Fed advisor Doctor Jeremy Rudd “Why Do We Think Inflation Expectations Matter for Inflation? (And Should We?)”, where the abstract says (emphasis mine):

“Economists and economic policymakers believe that households’ and firms’ expectations of future inflation are a key determinant of actual inflation. A review of the relevant theoretical and empirical literature suggests that this belief rests on extremely shaky foundations, and a case is made that adhering to it uncritically could easily lead to serious policy errors.”

Wow.

Never thought I’d see a rebuke of the current economic heterodoxy from senior Fed advisor.

The Fed is known for their groupthink, where their economists tend to be from the same universities and share similar schools of thought, where the institution tends not to be too diverse, and policies follow consistent orthodoxies.

Even on page 1, Rudd goes further:

“I leave aside the deeper concern that the primary role of mainstream economics in our society is to provide an apologetics for a criminally oppressive, unsustainable, and unjust social order.”

This all runs in contrast to recent testimony from Federal Chair Jerome Powell, where at Jackson Hole Symposium in August stated:

“Policymakers and analysts generally believe that, as long as longer-term inflation expectations remain anchored, policy can and should look through temporary swings in inflation. Our monetary policy framework emphasizes that anchoring longer-term expectations at 2 percent is important for both maximum employment and price stability.

We carefully monitor a wide range of indicators of longer-term inflation expectations.”

Rudd fights Powell’s statement in the very first paragraph:

“Mainstream economics is replete with ideas that “everyone knows” to be true, but that are actually arrant nonsense”

I have this same issue studying my own master’s degree in economics, where some of the assumptions that form the base of contemporary economic theory are so obviously false.

Take for example one of the three “laws” of consumer behaviour, transitivity of preferences – this hyperlink is to a really interesting academic study of human behaviour.

The idea is that if I prefer chocolate ice cream to vanilla, and prefer vanilla to strawberry, I MUST prefer chocolate to strawberry.

Au contraire mon frère, what happens if I SOMETIMES prefer strawberry to chocolate, especially if I haven’t had the flavour in a while?

This dynamism of the economic relationship can be the downfall of many an economic model where things work…until they don’t.

It’s the same (lack of) thinking that we’ve seen in the past year where raising wages would see higher employment right?

Well…..not if there’s a global pandemic happening and people are frightened for their lives, and hence, preferences can be transitive just as much as they are not.

Back to the Article

The orthodox view of inflation is that prices are a function of future prices, plus the differential between supply and demand

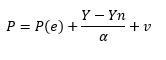

Mathematically stated, the Lucas aggregate supply function looks like this:

Where:

P = current prices

P(e) = expected future prices

Y = actual level of out/demand

Yn = natural level of output/demand

v = global supply of the good or service

Re-arranged to be better suited to micro-economics rather than macro-economics, we can write the function as a Phillips equation like so:

Where:

π = current price

π(e) = expected future price

m = corporate profit

z = wages

µ = unemployment

Rudd disagrees with this premise, showing that post 1995, the state of inflation dynamics reflects a situation where inflation does not enter worker’s employment decisions as employees have reduced bargaining power due to globalisation and smaller trade union influence.

This dynamic sees people no longer (or often don’t) leave their job because their wages aren’t keeping up with the cost of living, because they’re more worried about a prolonged spell of unemployment and having reduced income compared to steadily diminishing real take-home wages from lack of a pay rise.

This dynamic is entirely different to the Phillips Curve model of “adaptive expectations”, which are irrelevant if there is no (or less) attempt to leapfrog or make up for anticipated inflation in advance by negotiating a higher nominal wage.

Rather, the current period is one in which inflation isn’t embedded into the collective psychology of the labour force, and “isn’t on workers radar screens anymore (or is at least only a very tiny blip), which in turn yields an outcome where current price inflation does not respond (much) to past inflation (because inflation is not a major factor in wage determination).”

Practical Implications

Rudd seems to share a similar view to me that inflation is purely psychological and that we need to look at real-time indicators to measure workers decision making.

What should be evidence of concern is when price inflation starts to affect wage determination – either in labour market surveys, consumer and business confidence data or anecdotally in corporate reporting.

To that extent we would also want to determine whether people quitting their jobs is increasing, where that may be evidence of inflation affecting wage determination through the natural friction of the labour market.

Which for central bankers would say to them that their current models are useless and a reason why wage expectations and inflation expectations always seem to be incorrectly modelled and deviate from reality by 1-2% per annum.

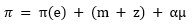

Source: US Federal Reserve discussion paper (September 2021)

This would also address the question whether central banks should continue with emergency levels of stimulus where the answer would be no, that the economic life support is supportive of asset price inflation but not the sought-after demand-pull inflation from increased wages.

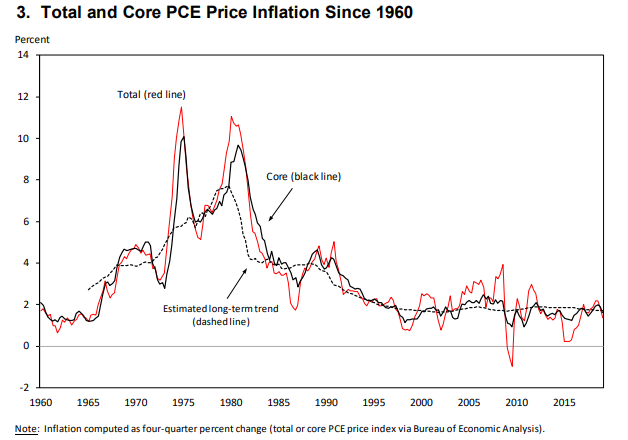

We can see this in the Australian market too where the RBA is well aware that wages have been frozen for more than 50% of our labour force this year.

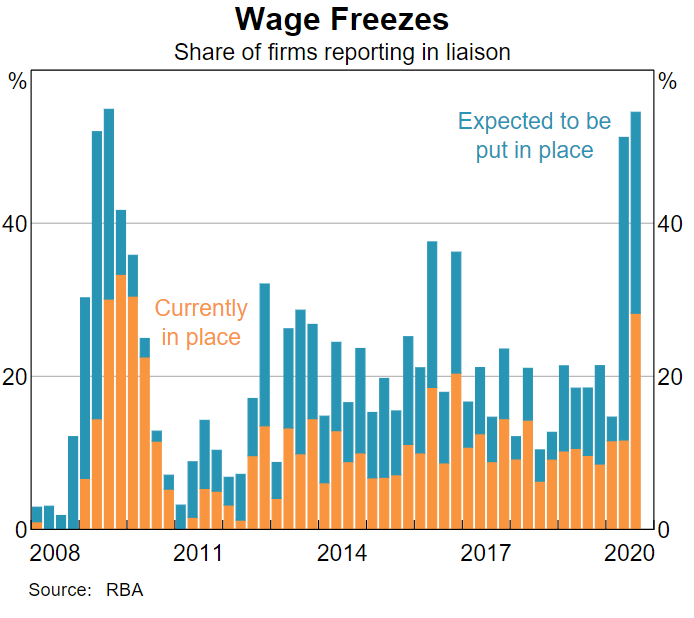

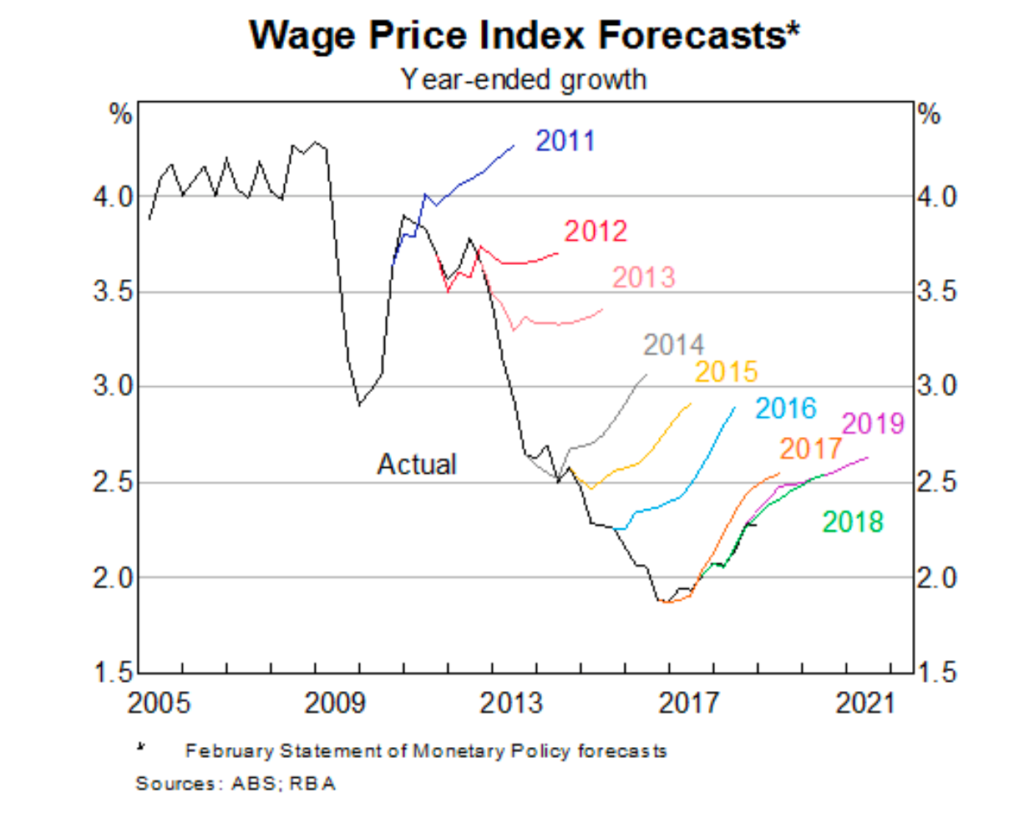

Yet here we are, using the same models that clearly haven’t worked for many years (as of February 2019):

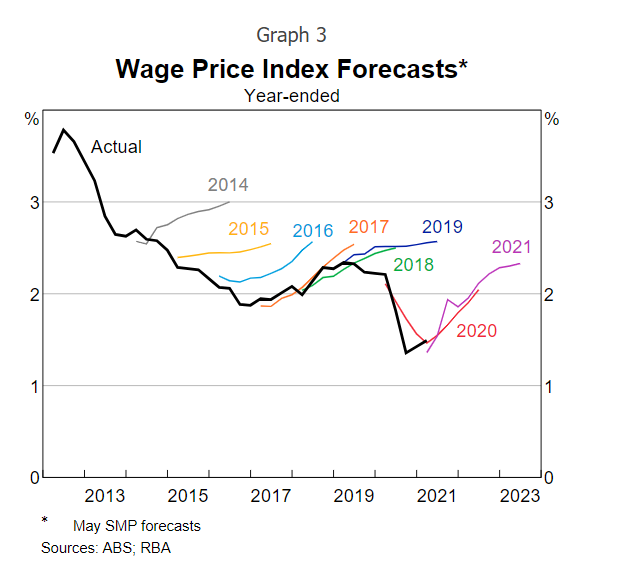

In fact, the RBA has changed the history of the chart because it was damaging to their reputation and credibility (as of May 2021):

Closing Remarks

I view the publication of this journal by Jeremy Rudd as positive for two reasons.

#1 There are central banking insiders who are upset with the groupthink embedded into the US central bank and are speaking out against it, seeking to elicit discussion and change

#2 The Bank didn’t censure the discussion and publicised a hyper-critical journal that may hurt the credibility of the bank, which would by implication be secondary to the primal importance of having a frank and honest discussion about their modelling and addressing any shortcoming.

Both are positive steps, that hopefully do elicit change and see the removal of emergency monetary policy support when it’s no longer needed.

The views expressed in this article are the views of the stated author as at the date published and are subject to change based on markets and other conditions. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Mason Stevens is only providing general advice in providing this information. You should consider this information, along with all your other investments and strategies when assessing the appropriateness of the information to your individual circumstances. Mason Stevens and its associates and their respective directors and other staff each declare that they may hold interests in securities and/or earn fees or other benefits from transactions arising as a result of information contained in this article.