There seems to be a lot of miscommunication and misinformation surrounding the topic of central bank tapering, and what the implications are for markets.

I’ve had a wide range of conversations with clients, some who think central bank tapering will have massive influence on markets, and others who think it’ll have next to no impact because this time around the tapering won’t be an unexpected exogenous shock, and more of a watching paint dry, sort of event.

As a primer for this note, Max recently wrote a recount of the 2013 “Taper Tantrum”, which was an event that spooked financial markets – particularly fixed income (bond) and equity markets – and was a learning experience for central banks around the globe.

Let’s spend some time today to establish common knowledge as to what tapering is and what the likely impacts will be.

Conventional Policy

Monetary policy is government agency initiated policy to establish a certain price of money – known as “qualitative easing”.

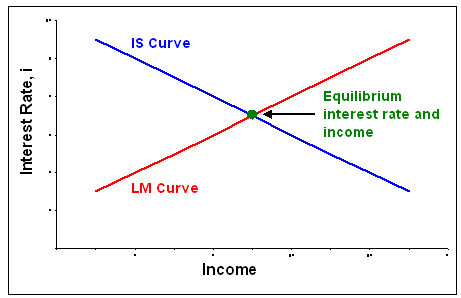

Conventional monetary policy does this by manipulating the private sector’s demand for money, to a point where money demanded equals to money supply, a macro-economic equilibrium part of the IS-LM model.

They do this by adding or subtracting funds from the money market, to change the aggregate level of supply and demand.

Source: Litterdale, T. (2004) – Intermediate Macroeconomics, chapter 6.1

This is mostly commonly seen in the use of the RBA’s Overnight Cash Rate or the US Federal Funds Rate, where the central banks set target cash rates, which becomes the overnight price of money.

This overnight price of money is used as a key determinant in the 2-day price of money and is part of the 1-month price of month, the 1-year price of money, and so forth.

These forward prices of monetary are joined to form a “yield curve”.

Where a yield curve is simply a forward-looking price of money, anywhere from overnight out to 30-100 years forward.

Unconventional Policy

As cash rates reached near (or below) zero percent, their effectiveness as a tool was largely exacerbated and central banks employed “unconventional” techniques to try and achieve their inflation and unemployment objectives.

In many central banks’ cases of unconventional policy, they sought to manipulate the demand for money by providing more money to the system, where they would create fiat money, and use that money to buy government bonds.

This would create a cash reserve at the bank who sold the bond to the central bank, who could then lend that money and consume or invest within the economy.

For example:

CBA sells $10 million AUD of 10-year government bonds to the RBA,

The RBA purchases the bond from CBA

CBA receives the cash for the sale.

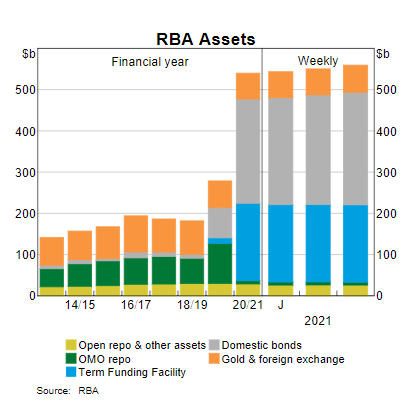

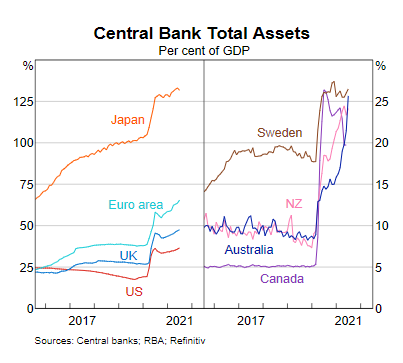

Central banks have done so much of this bond purchasing – also known as “quantitative easing” – that their balance sheets have grown into the trillions of dollars and continue to expand.

Yes, QE is still ongoing for most central banks, where they continue to purchase government issued bonds in secondary markets.

In the RBA’s instance, they are currently purchasing $5 billion AUD per month until September, where they are looking to then purchase bonds at $4 billion AUD per month until November or possibly (likely) longer.

In the US Federal Reserve’s instance, they are currently purchasing $120 billion USD per month, split between US treasury (government) bonds and US government agency issued housing bonds (“agencies”).

What is Tapering?

In both the above cases, as well as in Europe, Canada, the United Kingdom and many others, they are now seeking to reduce the asset purchase programs, where they won’t quit cold turkey, but rather they’ll taper their on-going purchases down to lesser and lesser amounts.

Less Gas, Not a Handbrake

What we’re talking about is not a hard stop to these purchases, nor is the potential tapering an unknown event that might spook markets like it did in 2013 – no, it’s a well forecast likelihood from central banks, where asset purchase programs will be slowly reduced to lower amounts and may not even be completely stopped at all.

Also, if these central banks start to fall short of their inflation and unemployment target, I’m sure they’ll be quick to add to their bond purchases, to provide cash (liquidity) to the market.

Hence, we’re not talking about a withdrawal of monetary accommodation or a reduction in liquidity, we’re talking about them adding less accommodation each month, but still an addition.

I’m most fond of using the act of driving a car as my metaphor: where central banks will be accelerating less, and certainly aren’t even close to pumping the brakes.

Pumping the brakes would be if they looked to SELL the bonds they hold on their balance sheet and withdraw cash from the market, or to hike overnight cash rates – both of which are unlikely to happen until 2023 at the earliest.

Likely Impact

Because of how well sign-posted monetary policy has become, there’s less likelihood that these central bank actions will negatively affect financial markets.

I wrote about new RBA policy approach in a note on 7 June, where the RBA (as well as other central banks) are using the following method:

#1 Release an academic paper discussing policy initiatives and the likely affects

#2 Publish articles about possible RBA movements using friendly sources to the RBA, such as the AFR or The Australian, where non-RBA officials can begin the conversation first.

#3 RBA insiders will speak at an event and suggest what the RBA may do, if and when economic data approaches their target levels for inflation and unemployment

#4 Assess the reaction of the market based on #1-3 and if no significant tantrum, then look to move ahead on a date they propose in the future, likely giving a couple of months’ warning

#5 Rinse and repeat for the next policy implementation

If you haven’t seen this happening already for yourself, I’ll give you this insight as a test.

On 26-July-2021 the RBA published an academic paper on the effects of macro-prudential tools in the Australian housing market, and how they can reduce credit growth in certain types of lending products.

Keep this in mind for the next wave of discussions from Australia’s Council of Financial Regulators as it’ll likely come up again soon, before becoming more wide-spread knowledge and then a policy response from APRA.

Likewise for the USA, we can expect some form of forward guidance regarding their asset purchase tapering likely at their Jackson Hole Symposium later this month, after the recent remarks of Federal Reserve Vice-Chair Richard Clarida’s remarks in the last week.

As part of this, the US is likely to begin tapering their $120 billion USD/month asset purchases in 2022, where it seems logical at this point they reduce the new purchases by $10 billion USD/month over the 12 months, then pause for a few months, then see if conditions are correct for them to hike their cash rate higher.

As for the RBA, they’ve already given us their forward guidance for the months ahead, and we expect them to start to taper in September-November 2021, with some flexibility in that time period depending on lockdowns and vaccination rates.

Closing Remarks

Because of the concerted action by global central banks to provide certainty and stability to markets in a time of uncertainty during a pandemic, they are in no rush to spook financial markets and possibly derail the economic recovery post-pandemic.

Using the above framework, they’ll likely take several months even upwards of a year to taper their bond purchase programs, and even then, may not completely stop them, where they may continue at a nominal amount.

For these reasons we think it’s unlikely we encounter a taper tantrum like we did in 2013, a panic would likely come from another source.

The views expressed in this article are the views of the stated author as at the date published and are subject to change based on markets and other conditions. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Mason Stevens is only providing general advice in providing this information. You should consider this information, along with all your other investments and strategies when assessing the appropriateness of the information to your individual circumstances. Mason Stevens and its associates and their respective directors and other staff each declare that they may hold interests in securities and/or earn fees or other benefits from transactions arising as a result of information contained in this article.