Earlier this year we experienced a steepening yield curve, where fixed-rate bonds – those most sensitive to interest rate and inflation movements – sold off to reflect a higher projected inflation risk and the likelihood of central banks tightening monetary policy, removing liquidity.

“Projection” is the keyword in the above paragraph, where economies were projected to overheat based on the reopening of economies conflated with the emergency levels of stimulus provided by governments and central banks alike.

The bond market sell-off was mostly short-lived, as the projections were somewhat forgotten amongst the rhetoric of “transitory” inflation, and where COVID 3rd and 4th waves reminded financial markets that the virus’s impact was longer-lasting than originally expected.

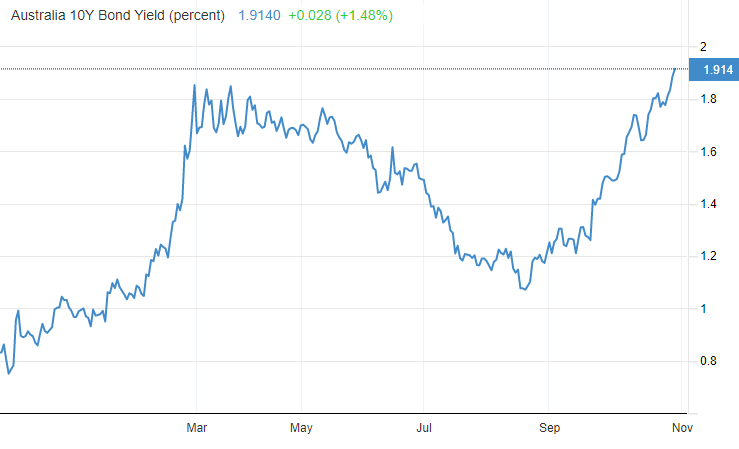

Fast forward to the past two months, and our 10-year government bond yields have risen quickly – just like they did in February/March, albeit at a less aggressive pace – now trading slightly higher than the Q1 highest levels.

Putting this in perspective, from 27-Jan to 27-Feb, 10y govies rose from 1.03% to 1.83% (+80bp).

This time around, from 21-Aug to 27-Oct, they’ve risen from 1.06% to 1.91% (+85bp).

This is important because while the surge has been sudden, the market is beginning to re-test the inflation is transitory narrative, where a push higher will be evidence of the RBA losing credibility and a renewal of projections for higher or more sustained inflation.

It’s equally important that this bond market sell-off has been more hesitant (and hence a slower movement) as it has been grounded in fundamentals, rather than projections.

Source: Trading Economics

Building a Background

While we’re focusing on the movements in the Australian yield curve in the past week’s news cycle, we should be aware that the precepts for this gyration started in other developed market economies.

What I would attribute as the initial catalyst for both this bond market sell-off as well as the Q1 sell-off, was the rationalisation of fiscal deficit spending.

We wrote about this in detail on 28-Jun, sharing the current economic orthodoxy behind a large portion of the Biden Administration’s infrastructure spending plans.

This was the first domino, that started to stir the animal spirits as to how aggregate demand could continue to outstrip aggregate supply, seeing prices rise higher and/or in a more sustained way.

This led us to August, where we reviewed both leading and lagging indicators of inflation and found that investor sentiment had reached an inflection point.

We dubbed this “Inflation is Psychological”, where despite the central bank rhetoric of “transitory” inflation, it was starting to persist and become embedded into wage-bargaining, creating a positive feedback loop or virtuous cycle.

From here we recommended that our Commonwealth government get ahead of the steepening of the yield curve – where we saw this coming – and take advantage of funding the Commonwealth by locking in the historically low yields by issuing longer tenor government bonds.

At the same time, it was made apparent by the RBA that they would remain dovish, maintaining their emergency levels of stimulus and liquidity for some time yet, continuing to peg government bonds yields at 0.10% until April 2024.

As this was fraught with danger where market realities may cause the RBA to blink, we recommended that investors position themselves at the short end of the yield curve, with less exposure or sensitivity to movements in market interest rates.

And then in late September and early October, everything began to speed up.

After postponing their originally intended cash rate hike in September, the Reserve Bank of NZ (RBNZ) tapered their QE program ahead of schedule and then hiked from 0.25% to 0.50% on 6-Oct.

On 17-Oct, Bank of England (BoE) Governor Bailey wrote to British newspapers over the weekend stating:

“the energy story means [the period of high inflation] will last longer”, and that the BoE will “have to act and must do so if we see a risk, particularly to medium-term inflation and to medium-term inflation expectations”.

With the BoE the first major global central bank to comment on the shifting of the inflation regime, the next domino fell with the Bank of Canada shocking markets last week, bringing an immediate end to its QE program and bringing forward its guidance on when it would achieve its inflation targets to mid-2022, from the end of 2022.

This change of view was (again) driven by higher inflation projections where “the upside risks are of greater concern.”

Australian Inflation

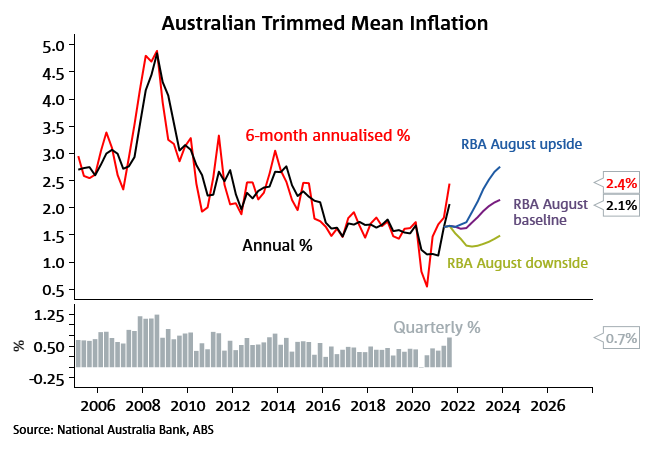

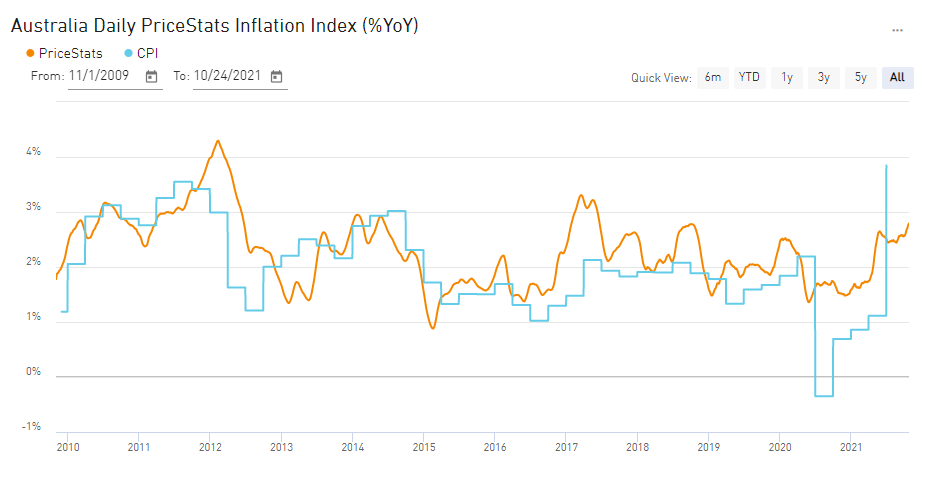

Also last week, the Australian Bureau of Statistics published Q3 CPI figures, where trimmed mean CPI (the RBA’s preferred measure of inflation) rose 0.7% q/q, to 2.1% y/y, the highest level of inflation since June 2014 and now into the RBA’s target band of 2-3% p.a.

A large part of the result was driven by retailers passing on higher costs due to supply disruptions where furniture and computing equipment prices had sharply risen throughout the quarter, at the same time that household construction costs rose.

The market looked through the result, where non-tradeable goods inflation had risen and could be projected to rise again in Q4 2021 and Q1 2022, as the supply disruptions were unlikely to quickly abate – though no evidence yet in Australia of a shift in wage-bargaining processes.

For that, we’ll need to wait until November 17th when we see the release of our latest Wage Price Index.

While inflation watchers such as me are well aware that CPI is currently elevated because it was underestimated last year, the change of market and investor sentiment has been dramatic.

Source: PriceStats, State Street Global Markets, as at 24-Oct-2021

The Australian Yield Curve

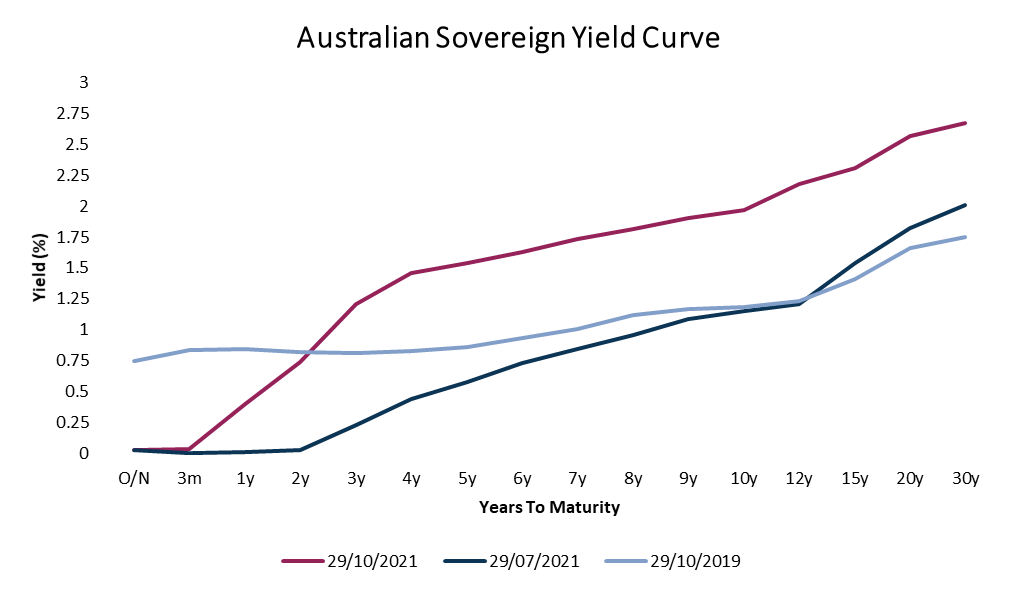

The release of CPI further awakened the animal spirits of Mister Market, where short end government bonds sold off aggressively, in open defiance of the RBA’s Yield Curve Control (YCC) peg, where the Overnight Cash Rate (OCR) out to April 2024 govies have been pegged at 0.10%.

On Thursday afternoon, the market tested the RBA where April 2024 govies were trading at 0.23% at the time.

The RBA did not conduct a QE event, buying the bonds to take the yield back down to 0.10%, and as a result, the yield exploded higher to 0.54%.

Note, the new steepness of the magenta line compared to the dark blue (3 months ago).

Source: Mason Stevens

Many in the market saw this as the RBA losing credibility and likely needing to pivot and change their forward guidance.

Under this view, we’d expect some form of relative hawkishness from the RBA’s upcoming policy meeting tomorrow, where they may raise the YCC target to 0.25% or may change the target bond from April 2024 to April 2023.

The alternative view: the RBA has let the YCC drift for a few days, time to time, over the past 1.5 years. It would therefore be realistic to envision them taking action next week after their monthly policy meeting, to give the market clarity over their position.

Given the latest comments from RBA Governor Lowe, it seems unlikely the RBA will capitulate on their forward guidance to the extent that the market is pricing in.

Nay, they would only be likely to do so in a small way, rather than admit they were completely wrong and erode credibility further.

Where to from Here?

Like we postulated in August, there is little edge to be had in gleaning which way bond yields are moving from here, as we can imagine a 2% handle for our 10y government bonds at year-end, similarly to how we can imagine the RBA stepping in to dampen the possibility of rate rises, seeing 10y govies trade back to 1.5%.

Hence, our view that we’d rather stay relatively protected in the very short end of the yield curve.

Also on our mind, is that the yield curve has flattened with short tenor yields rising quicker than long tenor bonds – known as a “bear flattener”.

Our yield curve flattening too quickly or becoming too flat may be negative for future economic growth prospects, as the market prices in higher borrowing costs which would be negatively impactful for growth – certainly individuals, households, companies, and governments with high indebtedness.

With this comes the possibility that Mister Market factors in lower corporate earnings, which would be negative for credit spreads as well.

Alongside this comes the opportunity to rotate into financial industry exposure, which tends to do well during periods of higher interest rates and consist of higher-quality companies with relatively better capitalisation.

Otherwise, and as normal, Australia will continue to see our economic growth and bond yields tied to global growth prospects, as a nation with a large sensitivity to international trade.

In this, we’d expect that another move higher in global inflation expectations would elicit a sympathetic reaction from domestic markets, moving our yields higher in the near to medium term.

The unknown is what the RBA is going to do about this – luckily, we only need to wait until tomorrow’s meeting to find out!

The views expressed in this article are the views of the stated author as at the date published and are subject to change based on markets and other conditions. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Mason Stevens is only providing general advice in providing this information. You should consider this information, along with all your other investments and strategies when assessing the appropriateness of the information to your individual circumstances. Mason Stevens and its associates and their respective directors and other staff each declare that they may hold interests in securities and/or earn fees or other benefits from transactions arising as a result of information contained in this article.