“Lower for Longer” – central bank monetary policy

“There’s no income in fixed income”

“How can bond yields move any lower?”

These are a small few of the expressions that we’ve heard over the last few years, reiterating the myths that fixed income bonds, usually referring to fixed-coupon securities issued by governments – government bonds – have low levels of income below that of term deposits.

We argue against these myths, where we’ve been able to provide 6.81% in the 12 month period to 30 June 2021, and have consistently provided a rate of return greater than RBA Cash Rate +2.5% (net) for the last 8 years.

Whilst government bond yields may be near their all-time lows, that doesn’t mean that investors should shy away from fixed income exposure.

No, 2021 is a time when investors should seek better ways to manage their fixed income investment, understanding the risks, returns and styles of management that may be appropriate for their objectives.

Starting From The Beginning

For close to seventy years, government bonds provided satisfactory levels of income, at relatively low levels of risk, that served as the ballast for diversified portfolios.

As bond yields (interest rates) slowly declined over the years and decades, portfolios continued to include sovereign bonds in their composition because of the utility they provided.

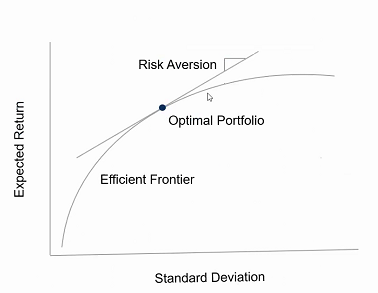

Utility is a key concept of portfolio theory where it is the marriage of both expected return and expected risk.

Equity assets, as opposed to fixed income assets, were perceived as a portfolio’s return provider.

They were expected to provide the lion’s share of return through exposure to growth and country’s expanding economic prosperity, where fixed income assets were included to provide known (fixed) income streams.

Also, fixed income bond prices would often be uncorrelated or inversely correlated with equity prices, thus providing diversification.

This diversification of risk premia within portfolios boosted portfolio utility and thus bonds continued to be included in investment portfolios for their utility benefits.

Thus, when combining a portfolio of equity and fixed income assets, we could optimise a portfolio.

Source: Mason Stevens

“Lower For Longer”

As you may have heard, the popular slogan for contemporary monetary policy is “lower for longer”, referring to lower interest rates, projected to stay low for a longer period of time.

While central bank policy is not the cause of low interest rates – it’s an outcome of global economic conditions – it does set the scene for an unacceptably low level of income for an investor that utilises a traditional approach to managing money, buying government bonds paying fixed-rates of interest (coupons) for their utility benefits.

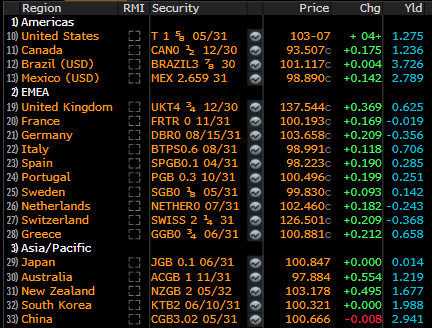

The below Bloomberg table denotes the yield to maturity (YTM) of 10-year government bonds for a range of global bond issuers, where most of the developed world are seeing yields below 2% and in come cases, negative.

Bloomberg World Bond (WB) Table, 10-year government bonds

Source: Bloomberg, as at 19-July-2021

Liquidity Versus Income Versus Diversification

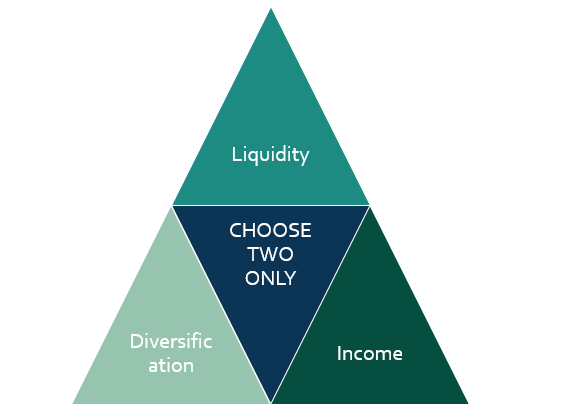

Looking at fixed income as an asset class in isolation, there are three key benefits required to make an investment allocation.

These are:

- The expected income or yield generated by owning the asset class

- Diversification benefits expected from other asset classes

- The liquidity an investor requires to buy and sell their assets

Liquidity is a concept we haven’t mentioned yet, where if fixed income is seen as the diversifier of portfolios and to provide the ballast for portfolio returns providing stability and income, then it likely needs to be sold at some point to provide cash, or allow capital withdrawal for lifestyle decisions.

Thus, fixed income securities need to exhibit reasonable liquidity to fulfill their role as a supporting asset class within investment portfolios.

Here lies the problem.

We’ve entered an environment where central bank cash rates have been lowered to historically low levels, which have in turn seen lower yields from fixed income assets.

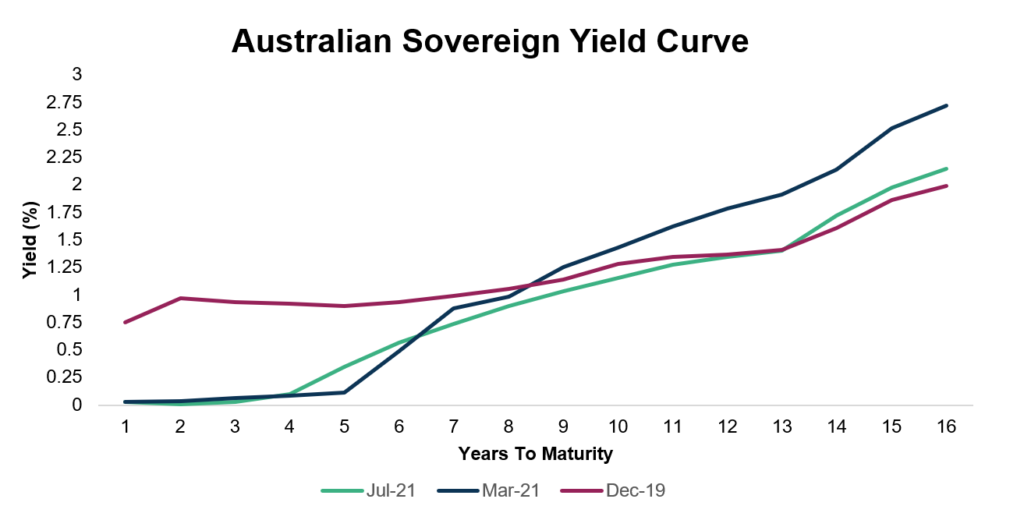

At present, a hypothetical investor would only see a 0.5% yield to maturity in purchasing 5-year Australian government bonds, or ~1.4% p.a. for a 10-year government bond, below many investor’s expectations or requirements.

Source: Mason Stevens

This has created a situation where either:

1/ investors need to revise down their return expectations, which could see workers needing to retire later in their lives in order to retire in comfort

2/ investors may seek incrementally higher risk exposure to obtain the level of income they expect

This dichotomous argument is where investors approach the economic trade-off between liquidity, income and diversification, not being able to get all three any more, they may only choose two.

- If still seeking liquidity and diversification >> will require lower income

- If seeking liquidity and yield >> will see lower potential diversification

Source: Mason Stevens

Enter Investment Grade Credit Bonds

In building portfolios in 2021 we need to recognise that equities remain the key growth driver of portfolios, while we have a trade-off within fixed income in balancing liquidity, income and diversification.

What has become a go-to strategy for many investors, is to utilise corporate issued bonds as opposed to solely using government issued bonds.

This has the trade-off that there is slightly less liquidity, but for many, the higher levels of income are an acceptable trade-off.

Also, we’re generally talking about large corporations that would nearly all be known to investors – bond issuers such as CBA, Westpac, Telstra, Coles, Fortescue, Qantas, Sydney Airport etc.

Credit Risk and Return

Corporations will in general, have slightly higher risk than a government who can always raise money via taxes or money printing.

As with any loan (or bond) there’s two main risks – both are part of a large concept called “credit risk”:

- Probability the borrower will default on their obligation to return the principal

- Probability the borrower will not be able to service their loan and pay their interest (coupon) obligations

As corporations have a slightly higher credit risk than governments, we are compensated by a higher yield or income than buying government bonds.

The difference is called a “credit spread”, which is the differential in yield between a government bond and a corporate issued bond of the same term.

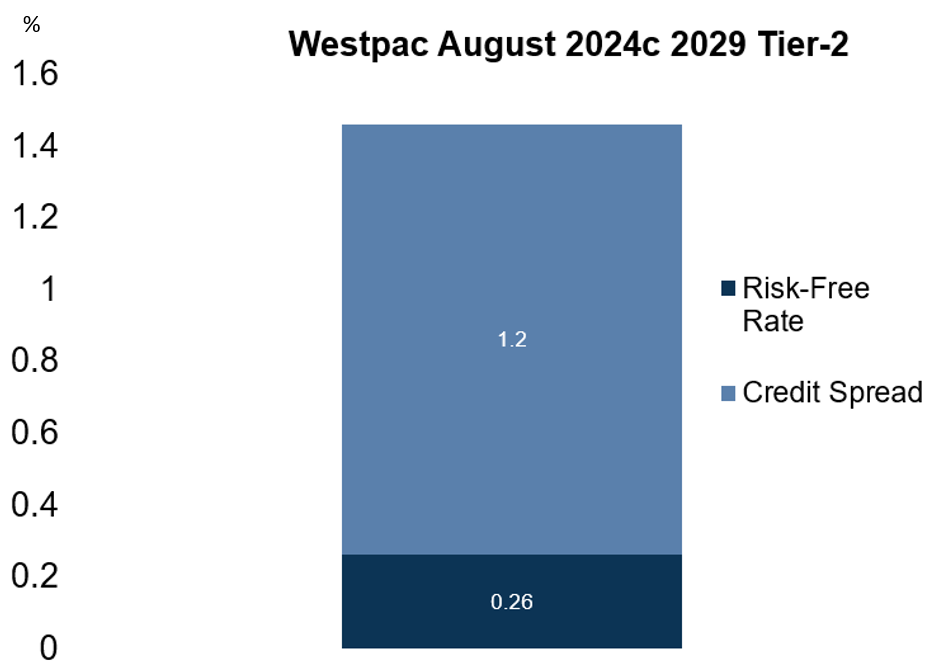

To illustrate this concept, we use the following example of a Westpac subordinated bond, where the components of the bond are:

- A government bond maturing in 2024’s yield = 0.26%

- Westpac issued subordinated bond redeemable in 2024’s yield = 1.45% p.a.

- Therefore Westpac’s “credit spread” is 1.74%, or 1.86%-0.12%.

Source: Mason Stevens, as at 30-June-2021

In this example, one could look at the Westpac bond and could evaluate whether an extra 1.74% per annum return was worth investing in Westpac versus the Australian government.

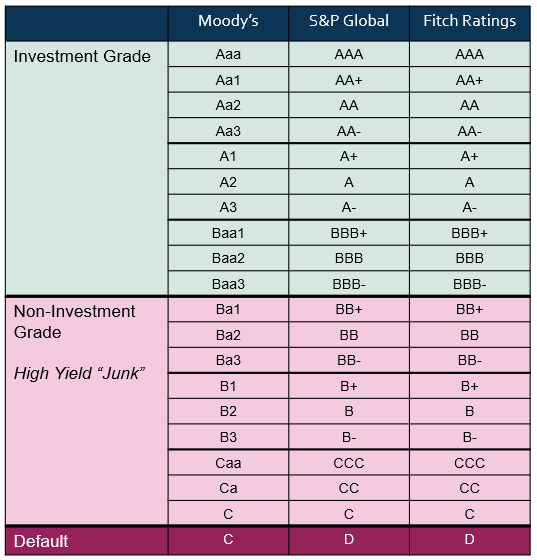

As for the risks, the market has self-regulated a practical way to assess both these risks, where specialist third-party institutions are utilised to derive the creditworthiness of a borrower.

These scores are called credit ratings, which are obtained by most sovereign nations, state governments and major corporates, as evidence of their borrowing capacity.

There are three dominant rating agencies by market share:

- Standard and Poors (S&P)

- Moodys Analytics

- Fitch Ratings

These three rating agencies have a largely homogeneous credit rating scale, that can be used by investors as their third-party assessment of credit risk, on top of their own due diligence.

Rating agencies use many metrics in determining their rating score for a particular issuer’s bonds, analysing their balance sheet, profit outlook, economic competition, macroeconomic factors and many others – all of which should provide an output rating that projects a lender’s probability of loss.

The less chance of loss, the higher the credit rating.

The more chance of loss, the lower the credit rating.

Generally speaking, a higher credit rating tends to mean lower yields compared to lower credit rating.

In building portfolios that contain credit bonds, we manage the risk-return trade-off to a commensurate level with our target levels of income/return.

Source: Moody’s, S&P Global, Fitch Ratings, Mason Stevens

Types Of Income

Similar to a home loan a household may obtain from a bank or non-bank lender, bond issuers (borrowers) can choose to pay their coupons (interest obligations) via fixed-rate, floating rate or even inflation-linked rates.

An example for each:

Company ABC may issue a 5-year corporate bond with a BBB+ credit rating at a fixed-rate of 3.5% p.a, coupons paid quarterly.

Or

Company ABC may issue a 5-year corporate bond with a BBB+ credit rating at a floating rate, paying a margin of 2.00% above the 3 month bank bill swap rate (BBSW) – a long-term benchmark of the Australian market used by banks within the short-term ‘Certificate of Deposit’ money market- , coupons paid quarterly, where the floating rate resets each quarter based on the 3m BBSW benchmark of that day.

Or

Company ABC may issue a 5-year corporate bond with a BBB+ credit rating at an inflation-linked rate, paying a margin of 1.50% above the Consumer Price Index (CPI), coupons reset and paid quarterly.

Each circumstance has pros and cons for the borrower (bond issuer), depending on their business and borrowing needs.

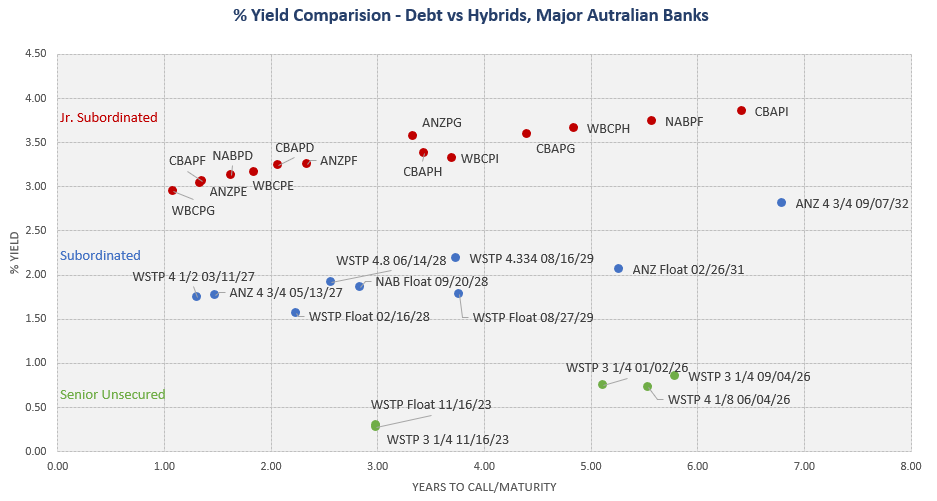

Types of Returns Available in Credit Investing

In terms of returns available to investors right now, here’s a small spectrum of what credit bonds are available in the Australian investment grade market at present.

Source: Territory Funds Management, Bloomberg 30-June-2021.

As you can see, there are many securities available, issued by large-brand name ASX-listed corporates, issuing investment grade debt, at what many could consider an attractive level of yield or income.

This is in part why we’re seeing increased allocation to corporate credit across the globe, as investors search for yield and income, not available in government bond investment.

Active Management To Navigate Volatile Waters

Given the nature of the COVID pandemic, the magnitude of central bank and government responses, and the mobility restrictions; these last 15 or so months have been constructive for an active style management of fixed income funds.

Initially, there was the knee-jerk reactions to COVID impacts and uncertainty that saw credit bonds sell-off as did equity markets, despite the large differences between the asset classes. This abated over the next 1-2 months and most investment grade credit bonds returned towards their pre-COVID price levels.

This was also a great buying opportunity for active managers who had adequate cash or liquidity so buy some of the under-valued bonds, similarly to how a “value” equity manager seeks under-priced equity assets.

This was quite an interesting time as subordinated debts issued by the likes of ANZ or NAB, issuers with great debt servicing scores and BBB+ credit ratings with low default probability, had seen a large sell-off in their bond prices. Hence, it was an opportunity for managers who had capacity to take advantage of the sentiment at the time.

While the market is not as dislocated as it was last year, there are still opportunities for active management in the 2021 calendar year.

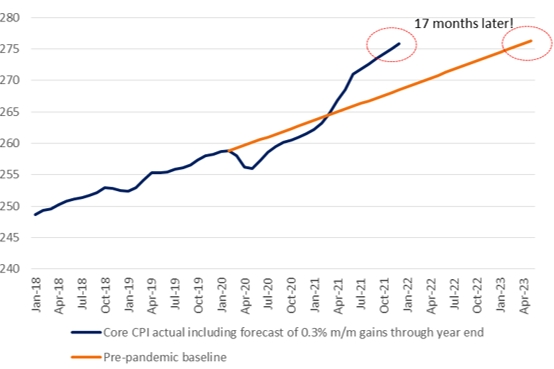

A large focus this year is on our global economic rebound from COVID and rising inflation expectations.

We’ve seen this already within the United States CPI, where it has surged above 4%, taking their CPI index to such a high value, it wasn’t forecast to occur for another 17 months!

US Consumer Price Index from 2018-2021

Source: Royal Bank of Canada, Haver Analytics

These higher inflation expectations have caused bond volatility this year, where fixed-rate bonds (paying fixed coupons) experienced capital volatility and sold-off, as inflation expectations had eroded their value.

It is worth noting this did not occur for floating-rate and inflation-linked bonds, whose coupons reset periodically and could capture the higher inflation or higher market interest rates.

With this being the case, it might seem to be a “no brainer” trade where a fixed income manager would either hedge their interest rate risk via derivatives, or rotate their bond exposure into floating and inflation linked bonds.

Passive fixed income, however, wasn’t able to make this rotation where active managers could, and we saw a period that passive underperformed active.

Below is a chart we shared with our investors in March 2021, where the Bloomberg Ausbond Compositive Index (mainly fixed-rate bonds) declined in value (blue line) while the Ausbond FRN index (floating rate) did not (orange line).

Source: Bloomberg

And this may well continue, as inflation expectations are still above our recent yearly averages, and supply disruptions causing the inflation have not yet abated.

Likely we see fixed income volatility and inflation ructions to occur again, requiring active management.

Choosing to invest in a Credit Fund

If a portfolio’s requirement for fixed income is that they provide a combination of liquidity, diversification and income, then investment grade credit is well positioned to provide reasonable liquidity, higher levels of income than government bonds and term deposits, with some levels of diversification.

Given the global backdrop, where central bank cash rates are not forecast to rise too far from their nadir, and the “lower for longer” government bond yield environment, the backdrop for credit is positive.

This should be supportive of investment-grade credit bonds, and an active approach that handles and navigates financial markets, and the slow withdrawal of government and central bank stimulus that has been common in the last 18 months, but will in time dissipate.

While there are known risk factors associated with this withdrawal of stimulus, but also the inflationary risk as economies re-open, an active approach should continue to suit domestic and international credit markets.

The views expressed in this article are the views of the stated author as at the date published and are subject to change based on markets and other conditions. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Mason Stevens is only providing general advice in providing this information. You should consider this information, along with all your other investments and strategies when assessing the appropriateness of the information to your individual circumstances. Mason Stevens and its associates and their respective directors and other staff each declare that they may hold interests in securities and/or earn fees or other benefits from transactions arising as a result of information contained in this article.