We are due to have elections in both upper and lower Houses of Parliament this year, and it was widely expected this year’s Budget would be an “election-year Budget”, where there is typically more deficit spending relative to other, non-election years.

As such, the Coalition government was relatively more forthcoming in releasing some of their Budget proposals early, which smoothed the reaction function of financial markets, where less was open to uncertainty.

In keeping with our template for analysis of previous Budgets, in today’s note, we don’t belabour the specific policies contained within the 350+ pages Budget papers, where it’s likely you’ve already read the main ones already or watched the Budget directly.

As such, we’ll focus on the implications of the Budget for financial markets; with the caveat that like all Budgets, they are proposals that then need to be ratified, and a change of government in the forthcoming elections may make the Budget irrelevant soon enough.

A Short Summary of the Budget

As with most Budgets produced by both major parties in the two decades, they use quite conservative estimates that are likely to surprise to the upside.

It’s for this reason that the “surprise” windfall was expected, and also seen in monthly budget statements where mining royalties, as well as GST take, were above the MYEFO forecasts.

The Government announced almost 40bln of new spending across five years from FY2021/22, quite a bit more than expected, and most importantly, more than half of this is set to occur in FY2022/23.

This adds to aggregate demand when economic growth is already strong and creates the impetus for the RBA to hike more strongly than previously forecast, as the Budget is decidedly more inflationary than previously forecast.

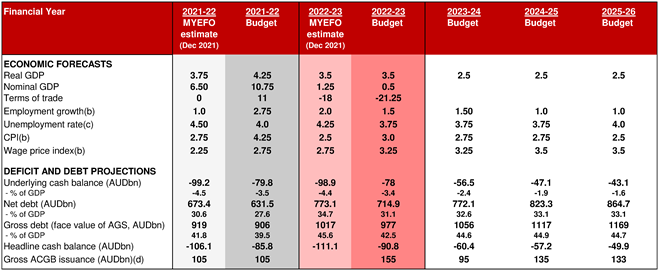

Table 1: Key Budget Forecasts and Projections

Source: Australian Commonwealth Treasury, Nomura

Deficit/Surplus Outlook

Budget deficit forecasts have been reduced by about 20bln AUD p.a., with strong macro outcomes boosting revenue by around 39bln AUD, partially offset by revenue and spending measures that cost the Budget 8 and 9bln respectively.

The deficit forecasts are better than MYEFO projections last December but still not as low as was expected.

In this Budget, the government appears to have turned away from their fiscal consolidation (austerity) strategy of yesteryear and sought to simply grow the economy to stabilise debt-to-GDP metrics, rather than reduce the outright level of debt.

This allows for voter-friendly initiatives, ahead of the election.

As Commonwealth Treasury have forecast a 78bln billion AUD deficit (3.4% of GDP), then we have to fund this expenditure, and this will be principally done through bond issuance, rather than asset sales.

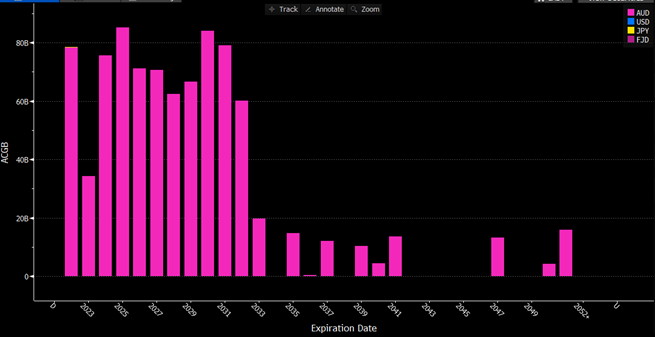

The Australian Office of Financial Management (AOFM), our national debt management office, has announced they will require 40 billion of net funding in FY2022/23 financial year – or 125 billion gross – accounting for bond maturities between now and 30 June 2023.

This is a revision downwards of last year’s MYEFO projection of 99.2 billion and wasn’t a surprise to bond market aficionados as the AOFM has already been issuing less in previous weeks, which was interpreted as an informal expectation of a lower required rate of funding to come via the Budget, than the previous MYEFO update or FY2021/22 Budget.

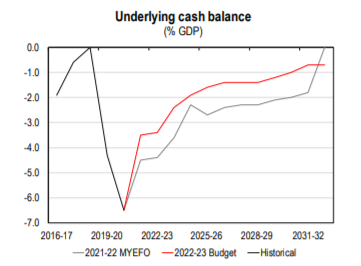

Hence, the forecast is for budget deficit spending to continue for the next 10 years – which is as far forward as Treasury projects.

Chart 1: Budget Underlying Cash Balance

Source: Australian Commonwealth Government, HSBC

Australia’s Credit Rating

As our federal government continues to run deficits and expands the gross or net national debt, there’s always questions this time of year about the viability of our AAA (S&P) sovereign credit rating, which if lowered, would likely increase the cost of funding for our Federal and state governments, and likely see a credit rating decrease to NAB, CBA, WBC, ANZ and Macquarie Bank.

Since the Budget and at the time of writing, S&P and Moodys have maintained their stable outlook on Australia, meaning it is not expected to be downgraded to AA+ in the coming year or two, which would be denoted by a “negative” watch alert.

Moodys has said the rating reflects the effectiveness of macro-economic policy as a response to the pandemic, but also the flexibility of the Australian economy to respond to changing circumstances.

Chart 2: Australian Commonwealth Government debt, currently at 876.2bln AUD

Source: Bloomberg, as at 29/March/2022

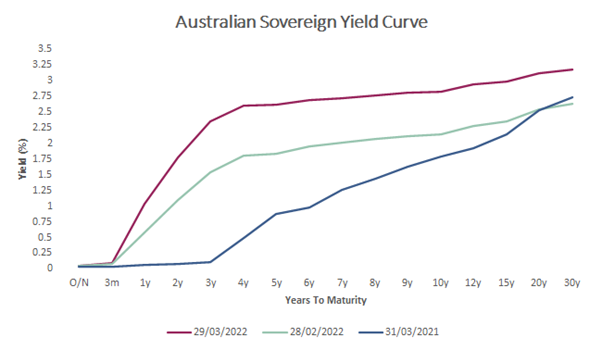

Yield Curve

Given the scale of the forward deficit profile and that infrastructure remains a Budget focus, there is likely to be ongoing upwards pressure on the Australian yield curve, especially within 10 to 30-year tenors.

This pressure should be a lot less than experienced in the past 10 months since last year’s Budget, where our bond yields have already risen dramatically in the second half of last calendar year, and first three months of CY2022 – as we forecast in May last year.

However, we are now moving towards a flattening bias between 3m and 30y interest rates as the impact of near-term US quantitative tightening (balance sheet reduction) impacts long-end bonds sending yields higher, which will likely not be as material as cash rate increases over the next 12 months, rising short term yields on the back of stronger national wage growth and increased government expenditure.

The amount of government spending extolled in the Budget – if passed – adds another reason for the RBA to remove monetary accommodation.

Also, given the recent US Federal Reserve hawkishness, the RBA should be placated by the lesser chance of rate rises creating unwanted AUD/USD appreciation, and the risks associated with the impact on international exports.

However, we’d caveat the RBA’s reaction function to likely wait and see until after the Federal election, before charting a clearer path based on the above information and circumstance.

All-in-all, a bias towards flattening 3m30y, but steepening 10y30y.

Chart 3: Australian Sovereign Yield Curve

Source: Mason Stevens, Bloomberg, as at 29/March/2022

Higher AUD bond yields are likely to be well-received by the market, where there’ll be increased demand for Australian government bonds because they retain a AAA credit rating and have relatively higher yields compared to similar AAA-rated countries (i.e., German Bunds at far lower yields).

Cross Market

In our view, Australia remains attractive relative to other nations on a “reward for risk” basis, and the Budget should not alter this fact.

While we’ve already noted this is the case for our yield curve, it’s also relevant when analysing Australian equities versus global alternatives.

For example, current ASX 200 P/E is 16.2x, compared to the S&P 500 at 23.6x.

This isn’t to say that a simple P/E relative value can capture the whole relative value trade, however, it does highlight that Australian equities could be seen as a “value” trade, where corporate earnings may be less sensitive to higher interest rates and changes in price-earnings multiples.

Chart 4: Comparing the ASX P/E (top) vs S&P 500 P/E (bottom)

Source: Bloomberg, as at 29/March/2022

AUD/USD

The Budget ultimately doesn’t change our view on the currency either, where the AUD remains buoyant on the back of bond yields (carry) and commodities – the dominant factors at the moment – though with a more negative outlook due to ongoing COVID and Chinese lockdowns – all part of our four C’s currency framework.

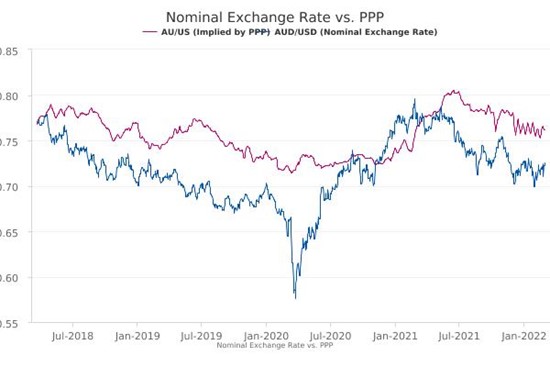

On a purchasing power parity (PPP) basis, AUD is undervalued relative to USD, and the exchange rate should be ~78-79c, instead of 75c.

Chart 5: AUD/USD Nominal Exchange Rate (blue) vs AUD/USD PPP Implied Exchange Rate (magenta)

Source: PriceStats, State Street Global Markets

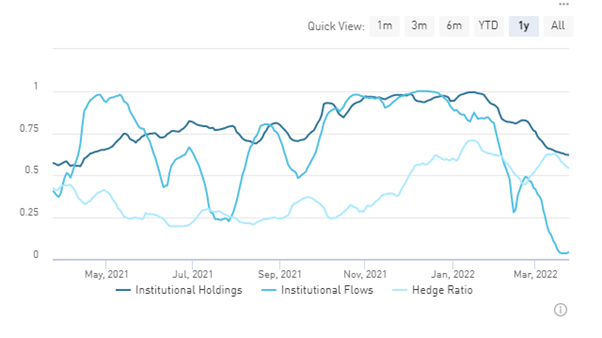

Though we note that AUD/USD is still seeing positive media coverage (source: MediaStats), though long positions are being trimmed by institutional investors (seen in custodial flow data), as investor behaviour was very bullish in Q1.

Chart 6: AUD Custodial Holdings, Flows, and Hedging of FX Risk Ratios

Source: State Street Global markets, as at 23/March/2022

Closing Remarks

Last Budget there was the looming spectre haunting the Budget as to whether the majority of Australians could be vaccinated, and we’d see hospitalisation rates decline.

This happened, which resulted in a stronger than expected rebound in consumer spending and mobility.

At present, our daily case numbers are tracking at >50k cases/day, though hospitalisation rates remain low due to the relatively milder Omicron BA.1 and BA.2 strains.

It’s likely the current Government will “sell” this Budget for the next two weeks before calling an election on April 11th, with the election likely to be held on May 14th or 21st.

The Opposition has indicated that they will support the currently proposed cost-of-living adjustments announced, but should the Opposition be elected, a revised Budget is likely to be delivered later this year.

The Budget is of critical importance for the Coalition Government’s re-election hopes as it trails around 55-45% on a two-party preferred basis in political polls.

For financial markets, it’s less relevant – despite the >50% chance the current Government isn’t re-elected – because the focus remains on international and domestic influences for strong demand, government spending, supply chain disruption and global impacts on energy prices and possibility for demand destruction lest energy cost too much that more people are marginalised.

Hence, likely that cost-of-living, wages growth (or lack thereof) and the current Government’s track record of handling floods, fires and the pandemic will be the key election issues.

The views expressed in this article are the views of the stated author as at the date published and are subject to change based on markets and other conditions. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Mason Stevens is only providing general advice in providing this information. You should consider this information, along with all your other investments and strategies when assessing the appropriateness of the information to your individual circumstances. Mason Stevens and its associates and their respective directors and other staff each declare that they may hold interests in securities and/or earn fees or other benefits from transactions arising as a result of information contained in this article.