Whilst financial markets have remained largely fixated on energy markets throughout the Russia-Ukraine crisis, an impending hunger crisis has been festering in the background which could have grave implications for the global economy, as well as on the health and wellbeing of billions.

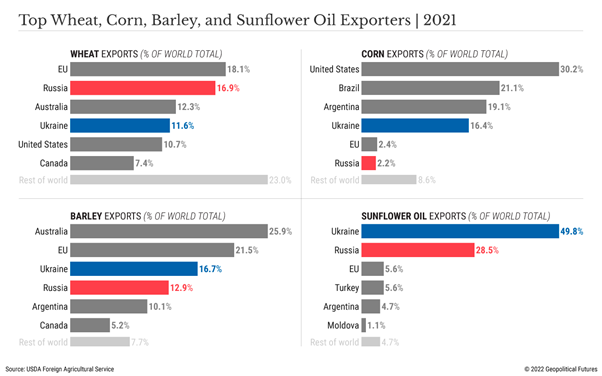

Although it has been established that Russia and Ukraine play significant roles in the global agricultural industry through acting as some of the largest exporters of wheat, barley and other grains, what has oft been mentioned is the impact which is being felt throughout the entire global agricultural supply chain.

To understand the enormity of the situation, we need to first look back on the many steps within the agricultural supply chain.

Steps in the Supply Chain

One of the first factors which comes into play for farmers is energy, given it determines the cost of running machinery which plants, harvest and processes crops.

Fertilisers also play a key role, and are used widely and come from either nitrogen, phosphorous or potassium (also referred to as potash).

Whilst not necessary, they are used by most as a means to bolster production and are often required in areas where climate or soil are not suitable for intensive farming.

Fertiliser markets fluctuate in valuation, so their price can often partially determine the economic viability of planting crops.

The cost of fertilisers can also often be linked to energy prices, given the energy intensive processes used in fertiliser production, where approximately 98% of ammonia (a form of nitrogen-based fertiliser) is produced through the catalytic steam reforming of natural gas.

Once crops are harvested, the nature of comparative advantages mean that the distribution of crops around the world remains largely centralised within certain nations who boast greater land, and more arable soil.

Issues like geopolitical tensions, natural disasters, increasing freight costs can result in varying levels of global supply.

A breakdown in either energy or fertiliser markets, or even distribution channels can create significant disruptions, but what we are currently seeing is a breakdown in all three.

Should conditions maintain their current trajectories, we will likely see significant reductions in global food production – though the locus of impact will be distributed in a non-linear fashion, where developing nations will be worse hit given the domestic agricultural capabilities of developed nations, and their greater ability to maintain strategic reserves and afford significant price increases.

As the topic of today’s note, we will cover the potential global hunger crisis – through the lens of energy markets (in relation to agriculture), fertiliser markets and global agricultural production as a whole.

Everything Starts with Energy

One of the largest costs for most farmers is diesel – which is required to run machinery during the process of planting, harvesting and processing crops.

Much like oil and natural gas, diesel markets have been enduring a torrid time, though the outlook for future price movements is arguably bleaker.

While oil prices have been reaching multi-year highs, their levels of consumption are yet to return to pre-pandemic levels, with price movements largely occurring due to supply disruptions despite the ability of some OPEC countries to bring more production online without much stress.

In diesel markets, prices have been driven up by all-time high levels of demand, due to the strong recovery from COVID-19 in transportation and freight.

Refineries have struggled to match demand and will likely continue to struggle given rising costs – where many use natural gas (whose prices are also at multi-year highs) to produce hydrogen, which is then used to remove sulphur from diesel.

Chart 1: 5-year Performance of Diesel (green), Natural Gas (red)

Source: Bloomberg, as at 1/4/22

Knowing all this, the implications are that agricultural prices will be higher globally, but particularly in Europe where energy supply chains are disrupted further – where levels of production could also be lower should rising energy prices make planting crops economically unviable.

A fix to this particular issue would require Russian oil, diesel and natural gas to return to the market immediately, or equivalent increases in production from other countries.

Such an increase is particularly unlikely for diesel markets, given those countries which are able to add supply, typically possess oil which is high in sulphur, which is not as suitable to be converted into diesel.

Not So Fertile Markets

The next step in the supply chain are fertilisers, whose valuations have risen dramatically on the back of withdrawn supply and rising energy costs.

Russia, who acts as the largest exporter of fertiliser in the world, has halted all exports in reaction to global economic sanctions placed on the nation, sending fertiliser prices through the roof.

Chart 2: 5-year performance of the Green Markets North America Fertiliser Price Index

Source: Bloomberg, as at 1/4/22

Within potash markets, prices have risen by over 300% over the past year, on the back of Russia withdrawing supply (who are the 3rd largest exporter), and due to the sanctions placed on Belarus (who are the 2nd largest exporter) in June of last year by the EU due to human rights violations – with their largest state owned miner also recently declaring force majeure.

Chart 3: 5-year performance of Brazil Potash CFR (USD/tonne)

Source: Bloomberg, as at 1/4/22

Nitrogen based fertiliser (primarily ammonia) prices have also sky rocketed, given they utilise natural gas in their conversion process – with many plants reducing capacity due to the enhanced costs of production.

These effects are being felt throughout the world – highlighting how the current problem lies not only in the removal of Russia and Ukrainian agricultural exports, but also in the global fertiliser supply chain.

In order to return to more normalised market conditions, Russia must return to supplying fertilisers to the world – which is currently unlikely given their demands that these exports be funded through Russian rubles.

The Final Product

Currently, the most publicised element of the agricultural supply chain has surrounded the role of Russia and Ukraine in exporting wheat and other grains to the world.

Source: USDA Foreign Agricultural Service, Geopolitical Futures

Given the conflict in Ukraine, and the economic sanctions placed on Russia, both nations have been largely unable to export many of their agricultural commodities.

The situation also looks likely to worsen, as we are within the spring planting season, where farmers in Russia and Ukraine have either halted planting activities, or significantly reduced their scale due to fears of being unable to export these goods, or being within an active warzone.

Whilst many nations still produce the majority of their agricultural consumption, other countries like Egypt rely heavily on imports, and have been feeling the squeeze in recent weeks from higher prices, and reduced supply.

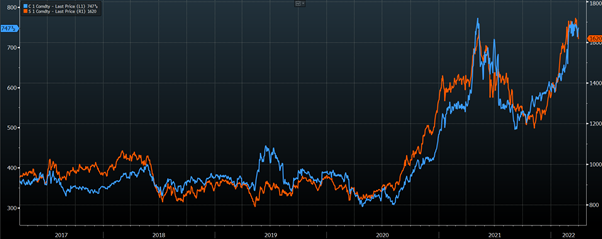

Stockpiling and rising fertiliser prices are also having impacts in agricultural markets in which Russia and Ukraine have little involvement in, like corn and soybeans, highlighting the market wide impacts of the conflict.

Chart 4: 5-year performance of corn (blue) and soy beans (orange)

Source: Bloomberg, as at 1/4/22

What we will likely see going forward is a bifurcation of impacts between countries, where developed nations will fare better given their ability to accumulate strategic reserves and their tendency to have stronger food security through maintaining healthy domestic agricultural industries.

Within developing nations, the prospect of a humanitarian crisis is apparent, where it is likely that the number of undernourished people in the world will sadly grow from the current number of 768 million – unless we see significant global intervention and/or arrive at a quick peace deal.

The World Could Go Hungry

Given our strong domestic agricultural industry, it is unlikely that Australians will have issues in sourcing food in the months/years to come.

However, given rapidly increasing prices of energy and fertilisers, it is likely that all nations around the world will see increases in price over the short-medium term, adding yet another tailwind to inflation.

For markets, the implications are two-fold.

Given rising agricultural prices, it is much more likely that inflation will remain higher and for longer, especially when considering the high price inelasticity of food.

Whilst energy markets and other supply chain issues may have greater impacts on inflation, what this does do is reduce the probability that we see the inflation fall to more manageable levels in the short-medium term.

Agriculture ETF’s such as FOOD:ASX and DBA:NYSEARCA, offer potential ways in which to hedge against rising agricultural prices, though more specific exposures can be achieved through investing into direct commodity ETF/ETN’s.

In order to hedge against this risk, some Agriculture ETFs can offer the ability for investors to gain positive exposure to rising agricultural prices.

The second implication this carries for markets is the likely move towards more domestic protectionism, where the agriculture industry has shown yet another example of the weaknesses of globalisation.

For corporates, this will likely see a continuation of the reorganisation of supply chains which has been occurring since the onset of COVID-19, driving costs higher as security and stability becomes a greater priority.

Domino Effect

While agriculture may not be front of mind for many investors, it’s important to remain cognisant of such topics given their ability to generate knock-on effects.

For example, increases in the price of food would reduce levels of disposable income (ceteris paribus), which would in turn slow down economic growth.

Food inflation would also place further upward pressure on bond yields, driving a multitude of implications for capital markets.

These are only but two linkages, where there are many more connections between commodity and financial markets which could have a material impact on portfolio performance.

To return to a sense of normality, Russia must begin exporting fertiliser, natural gas and agricultural commodities as soon as possible – whether this be a result of peace negotiations, or a partial removal in economic sanctions.

Without any of the above, and in the absence of scalable lab grown food production, the global economy will have to endure current conditions for the time being.

The views expressed in this article are the views of the stated author as at the date published and are subject to change based on markets and other conditions. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Mason Stevens is only providing general advice in providing this information. You should consider this information, along with all your other investments and strategies when assessing the appropriateness of the information to your individual circumstances. Mason Stevens and its associates and their respective directors and other staff each declare that they may hold interests in securities and/or earn fees or other benefits from transactions arising as a result of information contained in this article.