** This note is split into two topics, the first is regarding the latest Federal Reserve policy meeting and the second is regarding a recent RBA initiative to provide a backstop to the potential failings of deposit taking entities**

Topic #1 – FOMC

This week the US Federal Reserve’s Open Market Committee’s (FOMC) September meeting was anticipated by markets to “live” in that the Fed may seek to use the meeting to alter the current state of monetary policy accommodation available.

Personally, we thought it was much ado about nothing as we wrote on 30-August that Fed Chair Jerome Powell and other key officials had been signalling for weeks, providing “forward guidance” that they were going to remain patient until the end of the year for furtherance of their dual mandate objectives minimising unemployment and managing medium-term inflation to a ~2-3% price target increase per year.

In the 30-August missive, we detailed how the Fed had a million reasons NOT to tighten but only ONE reason to tighten, inflation, which they’ve been forecasting as temporary and thus not a medium-term view.

Therefore, it should come as no surprise that when the FOMC released their statement at 4 am AEST on 22-Sep (yesterday) that the market showed little to no reaction across bonds, currencies or equities.

Within the FOMC statement, the key passage was that:

“The economy has made progress toward these goals. If progress continues broadly as expected, the Committee judged that a moderation in the pace of asset purchases may soon be warranted.”

Furthermore, in the press conference afterwards, Powell said that “a reasonably good jobs report” would meet their taper test and that “I guess you could say the test on employment is all but met.”

Patient Powell indeed.

This also means the upcoming non-farm payrolls unemployment report scheduled for release on 9-October will be a key insight into whether the FOMC will taper in November, December, or later.

At the moment, the market consensus is for the taper to start in December, at a reductive pace of $15 billion USD per month, from the current $120 billion USD per month.

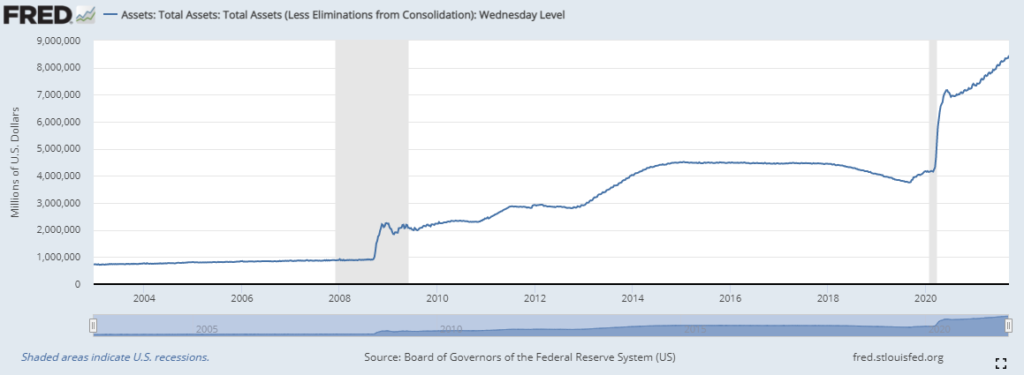

Hence, likely the Fed fully tapers their current QE program by ~July 2022, where their balance sheet will no longer continue to grow faster than the US economy, having grown from 3.76 trillion USD in Q3 2019 to 8.448 trillion USD as at 15-September.

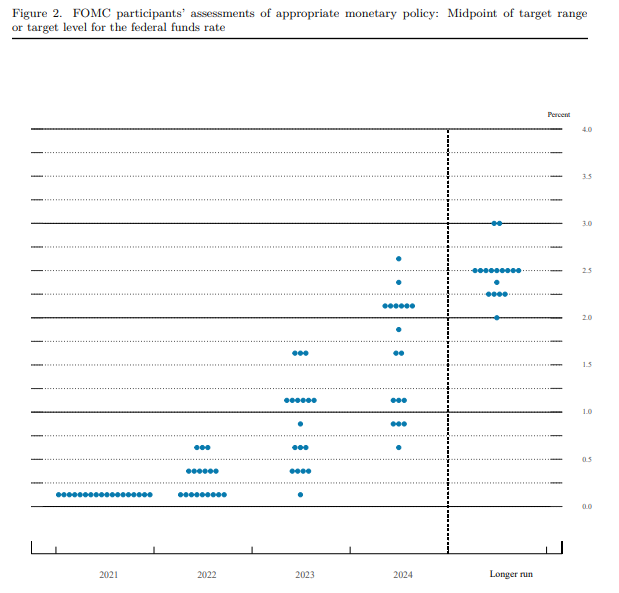

As for the forward guidance, the FOMC produced their quarterly “dot plot” which details the committee’s expectation for the cash rate in the coming 3 years.

2022 dot plot: the plot now sees 9 of the 18 FOMC participants penciling in a rate hike in 2022 where (obviously) the other 9 do not forecast any movement in the US cash rate next year.

2023 dot plot: the median dot is 1.0% in CY2023, which will require at least 3x 0.25% rate hikes during that year to get there, moving up from the current cash rate of 0-0.25%.

2024 dot plot: median dot is 1.75%, where 9 expect a rate of 1.875% or higher and the other 9 forecast 1.625% or below. We can’t help but feel this is them getting too far ahead of their skis, where 2024 is a long way away and a lot can happen between now and then to alter the current US economy’s trajectory.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank – Summary of Economic Projections

Topic #2 – The RBA’s “Other policy matters”

Typically, when the RBA releases their Policy Meeting Minutes, they’re worth a cursory glance at most and usually uneventful.

Their September 7th Minutes released yesterday, however, had a juicy section worthy of note buried towards the bottom under the heading “Other policy matters”, where the RBA Board discussed the Bank’s arrangements for a “Exceptional Liquidity Assistance” (ELA) facility.

An ELA is by no means a revolutionary concept, where the Italian and Greek central banks had adopted such a framework decades ago prior to joining the European Union and forming the European Central Bank.

However, this was one of those policy initiatives that the RBA had flagged in July through publication of an internal research paper on emergency liquidity provisions, supporting the argument that the Bank will continue to provide support to the Australian economy, and need to do so “for some time.”

As for some additional context, this doesn’t come across as a new policy, but it’s a formal adoption and policy framework for how to provide liquidity for any Authorised Deposit taking Institution (ADI), should the need arise, as opposed to the existing system that provides system-wide liquidity support.

Let me explain.

APRA requires that ADIs maintain liquidity buffers to account for planned outflows, called a Liquidity Coverage Ratio, formally part of Australian Prudential Standard 210.

This was part of a global banking resolution called the Basel III accords, where Australian banks will report on the “Three Pillars” requirements each quarter, which also includes their Net Stable Funding Ratio.

However, while ADIs maintain these ratios, it’s plausible that they may still have an idiosyncratic liquidity crisis where other ADIs may be relatively or totally unaffected.

As such, this is why APRA requires these ADIs to maintain strong capital buffers, as if required, they can pledge some or all of this capital to the RBA as collateral, in return for cash (liquidity) to remain solvent.

The system is therefore protecting the general public from backstopping ADIs from costing the taxpayer in needing a bailout.

What this also means is that it’s incredibly unlikely any domestic ADI becomes insolvent, while the RBA’s ELA exists.

They may experience severe losses due to credit impairments and bad lending practices – this is also assessed by APRA – but as long as they hold sufficient capital and collateral, the RBA should be able to provide sufficient assistance to weather any bank-run.

Also, the RBA Minutes detail that although “the focus of liquidity support is generally on ADIs, but in principle, it could also be provided to a domestic clearing and settlement facility, where the facility is unable to obtain liquidity from its collateral holdings for market or operational reasons.”

I would interpret this to be supportive of the ASX and Austraclear (owned by the ASX) too, creating a more robust system infrastructure.

All-in-all, making banking institutions and our financial exchanges more viable entities.

The views expressed in this article are the views of the stated author as at the date published and are subject to change based on markets and other conditions. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Mason Stevens is only providing general advice in providing this information. You should consider this information, along with all your other investments and strategies when assessing the appropriateness of the information to your individual circumstances. Mason Stevens and its associates and their respective directors and other staff each declare that they may hold interests in securities and/or earn fees or other benefits from transactions arising as a result of information contained in this article.