As primarily a fixed income investor, I spend an inordinate amount of time managing foreign currency fluctuations, as currency exchange rates tend to gyrate more than the underlying bond prices.

As an example, it doesn’t make sense to buy a USD bond with a 3% capital upside if I think the USD will fall 3% or more against our AUD.

Likewise, foreign bonds with lower yields can be suitable investments for their capital stability if their respective currency is expected to outperform.

I.e. buying Japanese bonds if we forecast JPY will outperform AUD over our outlook.

Today I’ll share our macro-economic outlook and views for key currencies.

Currencies in 2021

Foreign currency exchange rates are likely to continue to be determined by global factors in 2021 and the recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic.

The US election is still a focus as the Senate race hasn’t been determined yet, which will set expectations for the US dollar (USD) that will affect most other major currencies under our purview.

Let’s start there to set the backdrop for all currency forecasts.

Spotlight on the US Dollar (USD)

There are mixed fortunes for the USD in 2021.

The USD acted as both a safe haven during 2020, rallying on back of the COVID outbreak, but also sold-off on higher relative levels of fiscal and monetary stimulus causing fears of a USD devaluation through the increased supply.

The price action was also mixed as the demand for safe-havens waned as risk-on and “reflation” optimism prevailed, which saw the USD sell-off in H2 2020.

Because the US election result is finalised in Presidency and House, and soon the Senate (4 Jan), the market is able to forecast a stronger USD than previously anticipated, due to the expected split House vs Senate result. This means there will be no ‘Blue Wave’ resulting in mass amounts of spending i.e. there is less chance of fiscal stimulus devaluing the USD.

This has already seen the USD sell-off come to a halt in the last month against the Euro (EUR), British pound (GBP), Japanese yen (JPY), Australian dollar (AUD), Norwegian krona (NOK) and Canadian dollar (CAD).

As the US election comes to a close, other FX drivers will likely supersede US politics as the dominate drivers of the USD next year.

The outlook for economic growth will be key, which at a global level will be the differentiator between COVID19’s effect on economic output and how quickly countries find and distribute a viable vaccine.

Hence, 2021 will be a complex year and not a simple case for broad currency strength or weakness.

Macro-Economic Factors

Before I dive into other currencies, now is a good time to discuss those other macro-economic factors, other than the USD, affecting currency trajectories and outlooks.

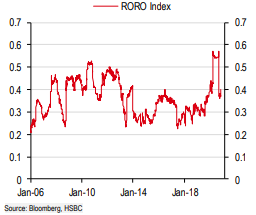

- Risk On / Risk Off (RORO): RORO was the market’s fixation on risk sentiment as the sole driver of asset price performance. This saw money flow into growth (equities) or defensives (government bonds, gold, USD, JPY) depending on the risk appetite of the day or week.

- Short term interest rates: Short term interest rates and the interest rate differentials between various countries were the drivers of FX performance and “carry” trades, but this has eroded over time as a large amount of nations have interest rates near zero% at present. The search for yield becomes more difficult.

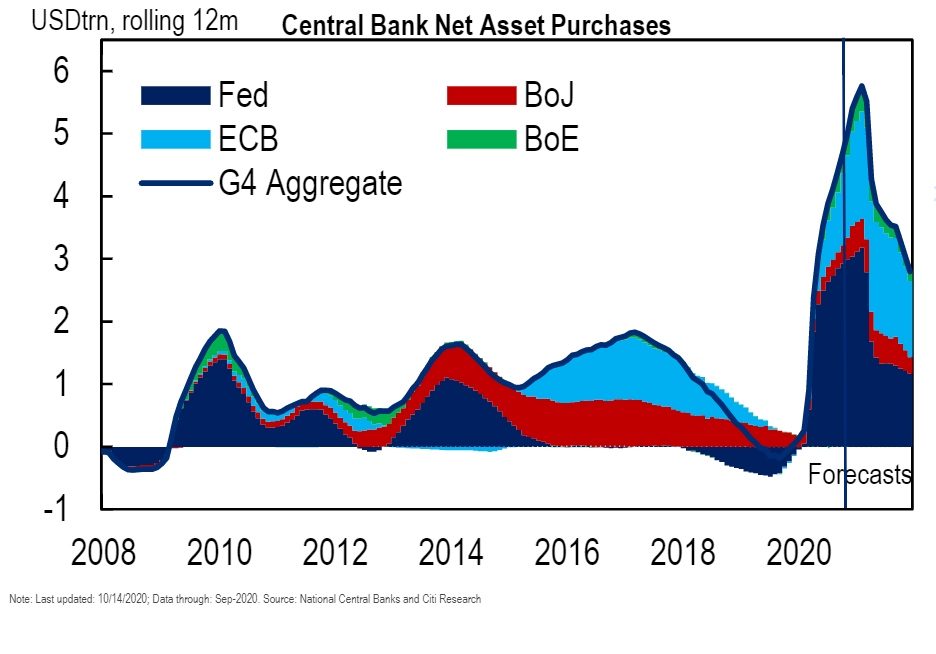

- Monetary policy: While short-term interest rates are not providing the fundamental differentiator for currencies anymore, the quantum of quantitative easing (secondary market bond purchases) is a key point of difference. The European Central Bank (ECB), Bank of Japan (BOJ), Bank of Canada (BOC) have much larger relative QE programs than the likes of the US Federal Reserve or the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA). Latest research out of the ECB shows their recognition of the size of their QE on the EUR-USD exchange rate, and why the rapid expansion associated with their QE is more associated with depreciating the EUR rather than targeting bond yields. This QE floods the market with EUR currency and with the large increase in supply, the currency devalues/depreciates.

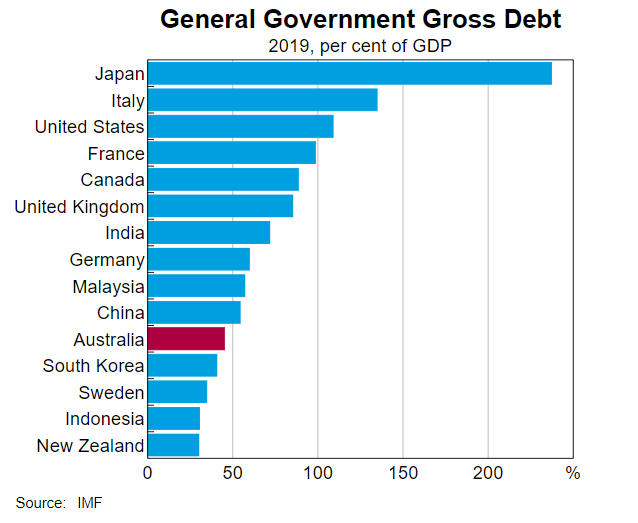

- Fiscal policy: Fiscal policy is likely to be the greatest of the differentiating factors as fiscal policy will underpin growth, especially if there’s another COVID outbreak or economic output shock in the near to medium term. This favours AUD, NZD, NOK and Swedish Krona (SEK) on this basis for 2021, given their relatively low debt-to-GDP levels. In contrast, we would therefore be more cautious on GBP and EUR. In emerging markets, this sees favour for Russian roubles (RUB), South Korean won (KRW) and Chinese Yuan (CNY) compared to Brazilian real (BRL), South African rand (ZAR) or Sri Lankan rupee (LKR).

Ready, Steady, GROW!

As fixed income interest rate differentials no longer offer the same signal they used to, we need to look directly at economic growth itself.

This may sound easy, but GDP is a lagging indicator, as is much of the input data that is slowly released.

For example, our Q3 GDP data was released on 2 December, more than two months after the end of the period.

Hence, we need to look at leading indicators and relative data to gauge the impact on currencies.

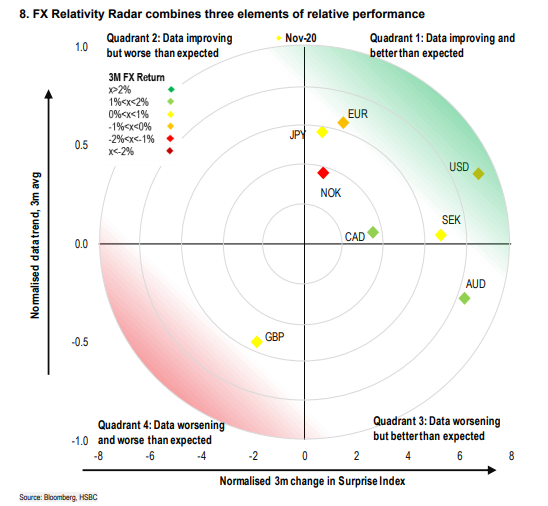

One way to do this is a “surprise” index, which many investment banks publish, such as Citi and HSBC, which conflates the economic data trend (improving/worsening) with the economic data itself (good/bad).

HSBC’s version is excellent (below) and can provide a high-level summary over rolling 3-month periods. Currencies in the top right quadrant are best placed under this metric.

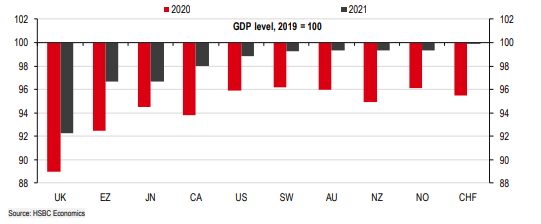

The other contemporary measure is to quantity the economic “scarring” associated with COVID-19 in economic growth projections.

This process assesses relative economic activity in various economies and whether the activity is reflected in currency valuations.

As a high-level summary, these cyclical growth factors favour smaller, open economies such as Sweden, Australia, New Zealand, Norway and Switzerland.

These factors are negative for the economies of UK, European Union, Japan, Canada and the US.

2021 Price Targets

Calendar year 2020 proved to be a trying time for FX forecasters as the currency cross-rates oscillated far more than historical averages.

This means that 2020’s forecasts, which were based on many of the macro-economic factors I’ve mentioned above, were rendered useless by March when COVID-19 became the primary driver of exchange rates and the resulting RORO trading regime.

What I’ve found is that FX strategists and economists are producing fewer forecasts and for shorter periods.

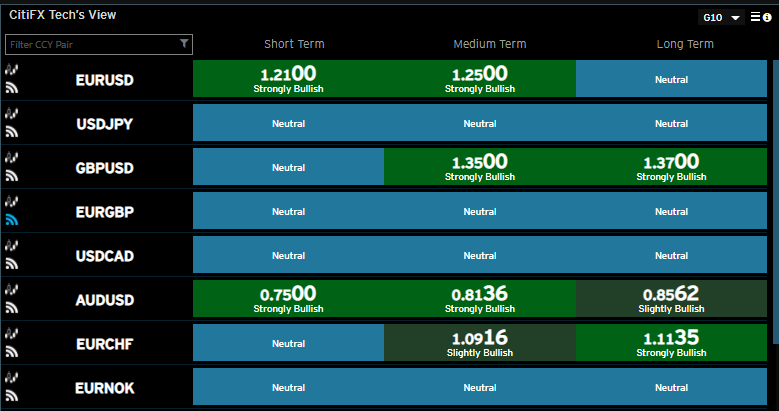

For example, Citi provide the following selection of forecasts, where there are only a handful of price targets and the majority of G10 currency pairs are “neutral.” They show each country’s economic backdrops are similar and responding to the same risks (COVID), so the currency will oscillate but with largely no differentiation or long-term trend.

Interestingly, I note their AUD/USD forecast is strongly bullish over the short to medium term, with a target of .85c over the longer term.

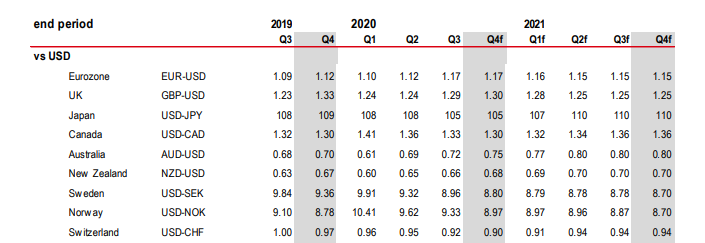

These targets are many orders of magnitude different to HSBC’s outlook for exchange rates, where they provide guidance for a larger range of currencies (30-40) but only for the next 12 months.

AUD/USD as forecast in contrast to Citi, has a target level of 80c by the end of 2021.

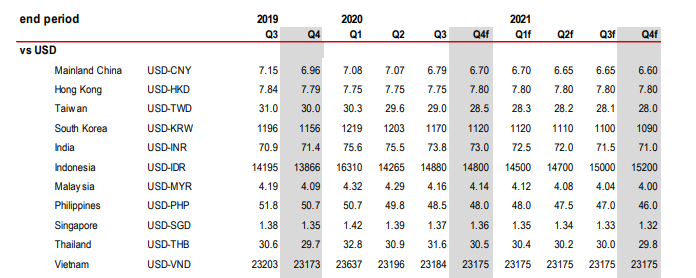

For those with interests in APAC currencies, the following show cross rates between USD and most major Asian currencies.

Forging an investment thesis

I can agree with Citi’s prognosis that relative currency valuations are not as differentiated by macro-economic factors at present, while RORO regime partially prevails, and while interest rate differentials are lower than average.

Hence, I can agree that many currency pairs will likely experience lower than average volatility in 2021, without any further catalyst to change this trading regime.

In fact, I argue that this is exactly the kind of volatility suppression that central banks are trying to elicit with their forward guidance, yield-curve controls and commentary such as (former ECB Governor) Draghi’s “do whatever it takes” monetary policy accommodation.

However, the relative drivers of exchange rates will emerge as small, open economies react quicker and more nimbly then larger nations with more bureaucracy and state/federal government controls.

Couple this with the industrial sector being the quickest to bounce back already from COVID-19 as fiscal stimulus is developing into infrastructure spending, demand for raw goods and minerals will continue to soar.

This sees smaller, open economies reliant on exports – such as Australia, New Zealand, Norway, Canada and Chile likely to outperform in 2021; though I note Canada may be an exception because of their transition away from oil exports.

Therefore, I see capital upside for taking currency risk based on my trade thesis, where these nations (AU, NZ, Chile, Norway) all have slightly higher interest rates too, which leads to carry trades.

As an investor with organic AUD based deposits, this currency outlook makes me less likely to take foreign currency risks, without access to hedging.

Of course, there may be foreign investments that are worthwhile in any currency based on their capital upside potential, but this is more the realm of an equity opportunity than a fixed income one.

The views expressed in this article are the views of the stated author as at the date published and are subject to change based on markets and other conditions. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Mason Stevens is only providing general advice in providing this information. You should consider this information, along with all your other investments and strategies when assessing the appropriateness of the information to your individual circumstances. Mason Stevens and its associates and their respective directors and other staff each declare that they may hold interests in securities and/or earn fees or other benefits from transactions arising as a result of information contained in this article.