For my Christmas present last year, my mother-in-law bought me a book written by Professor Stephanie Kelton, titled “The Deficit Myth”.

Due to COVID-19 related postage delays between the USA where my MIL lives and Sydney, Australia, I sadly didn’t receive the book until April this year, and now that I’m reading through it, I realise that a lot of the economic theories within are what underpin the current Biden Administration fiscal deficit spending.

For context, Prof. Kelton, a long time academic, is a senior advisor to the US Democrat Party, having previously served as a senior advisor to the 2016 Bernie Sanders presidential campaign.

Kelton has in the past also been named by Politico as among American’s top 50 “thinkers, doers, and visionaries transforming American politics”, also receiving a similar eminence from The New Yorker.

And if Kelton is an advisor to Bernie Sanders, whom is currently the chair of the US Senate Budget Committee, then knowing the policies she and other post-Keynesian economists are proposing is quite valuable.

With this background knowledge in hand, I had the opportunity to listen to Kelton present at State Street’s annual Research Retreat last week, speaking on the topic “Do Massive Fiscal Deficits Matter?”

Certainly, a big topic and of paramount importance this year – and potentially for the years to come as well.

The below are my transposed notes of the session – hope you enjoy.

Do Fiscal Deficits Matter?

The answer was a resounding yes, but they matter in a different way to which we’ve been taught historically.

If studying economics in high school, university or TAFE, we’re taught that governments face similar budget constraints to households, where they can only spend as much income as they take in.

Under this model, the only way to exceed spending more than your income is to borrow, where borrowing will be limited by your capacity to repay.

This model held true while countries maintained their currencies were redeemable into physical assets such as gold (“gold standard”) – but since the 1970s where the world entered a fiat currency regime – where currencies are not backed by anything other than the credit worthiness of the government issuing it – the model has decreased in relevance.

The change is that government’s control their nation’s printing presses, where they now have the ability to inflate the monetary supply and run fiscal deficits, without the requirement of borrowing from the private sector or taxation.

Which if you think about it, are nearly the same thing, a concept known as Ricardian Equivalence.

This, therefore, paves the way for a new economic concept, where a government spending more than their income is not fiscally irresponsible and only done for short or emergency periods.

In fact, that deficit spending could be sustainable.

Source: StephanieKelton.com

The US Fiscal Budget

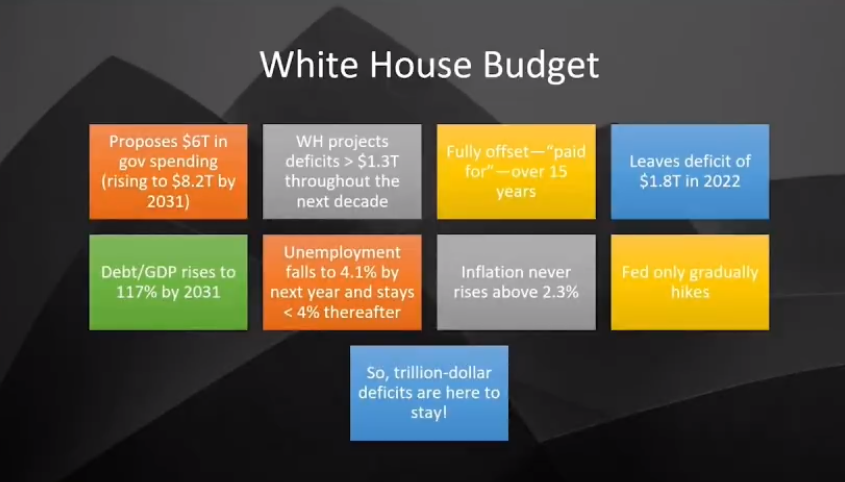

The White House has recently issued their federal budget, where there’s over 6 trillion USD of proposed spending.

Within the budget proposal – noting it is only a proposal until its legislated – the fiscal deficits are estimated to be 1.3 trillion USD on average for the next decade, with no surpluses.

If you’re aghast, please note that we’re in the same situation in Australia, with no budget surplus factored in until 2031/2032 fiscal year.

The plus side to the US Budget?

This level of spending is projected to see the US unemployment rate decline to 4.1% next year, and stay below 4% there afterward, at a level considered “full employment”, otherwise known as the natural rate of unemployment.

Also, under this scenario analysis, inflation never rises above 2.3% for a full calendar year, where the US Federal Reserve only gradually hikes interest rates, if required.

Source: StephanieKelton.com

Rejecting Existing Deficit Myths

If we’re evaluating whether fiscal deficit spending is “overspending”, then under this framework the answer is no, that it may actually be required if tax receipts are too low and higher levels of spending may be required to support the economy.

Likewise, if inflation is considered to be evidence of overspending, we’re miscategorising the causality of the rising prices of goods or services where they may be due to disequilibrium between demand and supply.

What this new theory proposes is that deficits are perfectly normal and nearly always necessary for a healthy economy.

Put otherwise, if someone has to spend more than their income to grow the economy, the question is who?

Most Important Chart in the World

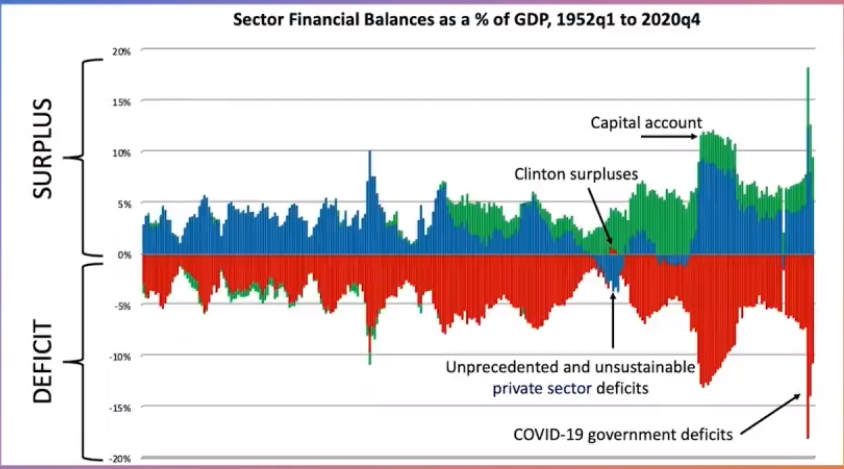

The following chart is a model used by Goldman Sachs former chief economist, and at the time Goldies considered this the “most important chart in the world”, which Prof. Kelton has updated to include 2021 data.

What we are seeing is that government deficits mirror private sector savings, where the private sector saves more, the government needs to spend more.

Therefore, investment allocations are more about figuring out who is increasing or decreasing their spending, to identify the areas of growth.

Source: StephanieKelton.com

While the above chart is from the US perspective, it also works in 20+ countries, such as Canada, Australia, UK, Germany, France, Spain etc.

[Note: I haven’t had the chance to examine the veracity of the above analysis from Prof. Kelton, and how pervasive the relationship is across multiple countries]

Government Debt Burden

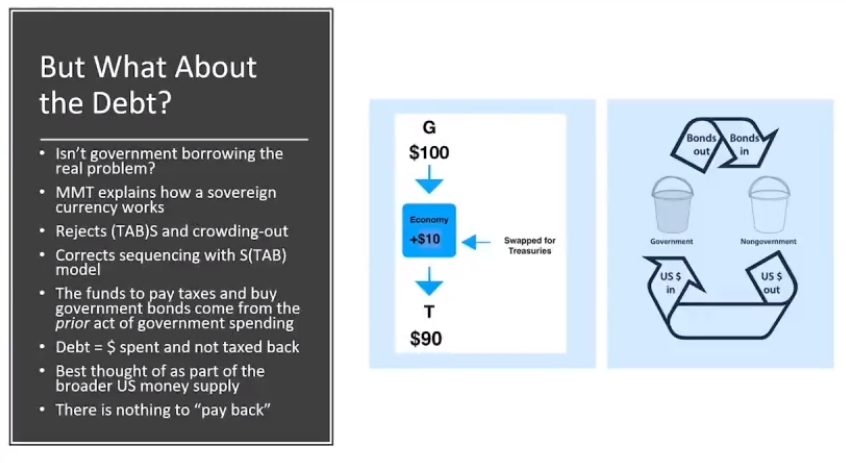

If government deficits aren’t a worry, then the next foreseeable issue will be about the amount of government debt outstanding, and the ability for the treasury to finance it.

What happens under the Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) model is that the central bank purchases a portion (or all) of the debt issuance from the Treasury department, where the money is created within the central bank ledgers and then transferred to the appropriate Treasury accounts.

This system therefore rejects the “crowding out” theory of debt markets, where otherwise, the government may issue too much debt and move bond yields higher to attract additional marginal buyers at a “market clearing” price level.

This isn’t the case as the central bank is buying the debt, so there’s no flood of debt issuance into the bond market.

Source: StephanieKelton.com

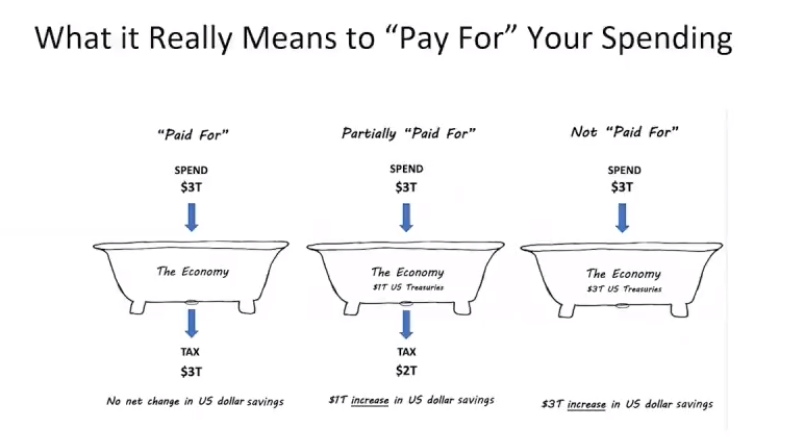

Paying For Your Spending

In the USA or if you listen to any form of US news media, you can’t escape the “who pays for it” narrative.

Professor Kelton used to work as an economic advisor to the Democrat Party on Capitol Hill and they usually focused on getting the highest proposed budget through the Congressional Budget Committee (CBO) with the lowest cost scoring.

What happened time and time again was that you got an endless situation of inadequate infrastructure spending and productivity initiatives because the short-term costs were the key focus of the CBO scorecard.

But that’s now changing.

Since COVID-19 struck into the US last year, call it the last 15-16 months, through the CARES Act as well as the 1.9 trillion USD spending in March this year, the US has been spending where the “who pays for it” was not as big a factor, nor has the “overspending” seen any sustained level of inflation across goods and services – though we did see it in specific industries, but again, mostly due to supply chain disruptions.

In picture form, the US has been working under the 3rd bathtub model in the below

Source: StephanieKelton.com

Limitations of MMT

The natural progression of the proposition is determining what are the limits – where the USA in particular has the exorbitant priviledge of being the world’s reserve currency.

For example, countries such as Ecuador could not run such high fiscal deficits as the USA, nor can state governments or local councils that don’t control their own printing press.

For this same reason, most European Union member nations are unable to as well, due to the lack of a fiscal union to accompany their monetary union.

The relevant constraint to the process is therefore inflation.

MMT is about replacing a “fake” budget constraint (“who pays for it”) and replacing it with the inflation risk of the Federal budgeting process (“overspending”).

Therefore, the correct way to evaluate Federal spending is to keep spending inflation neutral, rather than deficit neutral.

Taxes

Therefore, taxes are a way to dampen inflationary pressures, where they can be moved to subtract spending capacity within the private sector.

Question section:

- Why doesn’t Biden or Yellen use these terms in public forums if this is the economic lens they’re using for the Biden stimulus proposals?

- Words like debt and deficits have been weaponised by both political parties to beat up on each other, blaming circumstance on either party based on entitlement programs or against tax cuts which has created this inability to move past the “pay-for” argument, where we should by now

- Can infrastructre spending be done without limit?

- The infrastructure spending can be inflation mitigating, rather than aggravating

- i.e. we need to spend a lot of money to AVOID supply constraints, which avoids some inflation pressures and supply bottlenecks

- If there’s shortages in labour markets due to COVID, a lot of this due to women staying at home, then providing affordable childcare can help with this

- Same with R&D spending

- When economists like Larry Summers talk about the US overheating due to “too much water in the bathtub” he’s forgetting that by building infrastructure or increasing the labour force, they’re increasing the size of the bathtub.

- The infrastructure spending can be inflation mitigating, rather than aggravating

- If US inflation is not transitory, does this mean the deficit was too big?

- No

- Inflation can happen for reasons completely unrelated to aggregate expenditure such as supply bottlenecks, but likewise inflation can be too low because of labour market slack and underemployment

- Where these kinds of inflation aren’t about deficits

- Debt servicing ability of the US?

- This is to do with the subsidy provided through bond coupons to bond holders, where the MMT proposal doesn’t see higher interest rates if inflation is managed and the transfer payments are kept within the Treasury-Fed loop.

Closing Remarks

While I’m still unconvinced on the topic, I find reading theories that I disagree with (partially or wholly) truly interesting, as they challenge my view of the world and the prevailing economic orthodoxy.

And while I may disagree in some regards – as did RBA Governor Lowe via a speech in July last year – if this is the policy pathway the US is moving down under the current Biden Administration, then I need to be well aware if I’m going to try and profit from it within investment portfolios.

The views expressed in this article are the views of the stated author as at the date published and are subject to change based on markets and other conditions. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Mason Stevens is only providing general advice in providing this information. You should consider this information, along with all your other investments and strategies when assessing the appropriateness of the information to your individual circumstances. Mason Stevens and its associates and their respective directors and other staff each declare that they may hold interests in securities and/or earn fees or other benefits from transactions arising as a result of information contained in this article.