The COVID-19 pandemic has caused an enormous amount of disruption across the globe, re-directing spending, disrupting business models and supply chains, impeding personal mobility and shifting horizon preferences.

One very real disturbance, though a trend that is still in its infancy, has been the record number of employees that are quitting their jobs, or thinking of doing so.

According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), more than 15 million US workers have quit their jobs in the past 6 months, creating supply shortages all over the nation, something we’re also experiencing in Australia (though to a lesser degree).

This trend isn’t a short-term aberration either, it’s a more formal rebellion against establishment business models, where workers are voting with their feet, leaving expensive property markets where costs of living have outpaced wages, and seeking remote work opportunities.

In a recently published McKinsey Quarterly article titled “Great Attrition or Great Attraction? The Choice is Yours”, McKinsey surveyed 5,774 workers across Australia, Canada, Singapore, the UK and US along with another 250 managers and recruiters, to try and get a sense of the breadth of the shift in employment and sentiment, to provide actionable outcomes for both employers and employees.

Decision-Making Processes

What McKinsey highlight in their abstract is that employers don’t understand what’s going on and are reacting based on faulty assumptions.

This is nothing new under the Sun, humans tend to create “a priori” models that are subject to input biases, where faulty assumptions skew the theoretical from the practical.

This is opposed to posteriori models, which have no inputs and are based upon output results.

The answer is quite obvious: to better model worker behaviour or build corporate policy, employers and employees must engage in meaningful ways to create jointly agreed outcomes, lest the attrition continue.

The Great Attrition

As mentioned above, over 15 million Americans have left their jobs in the past six months and quite a large portion have not come back to the labour force.

Part of that is lockdown related, part of this due to different lifestyle preferences, where employers who believe the increased employee turnover is abating are misguided.

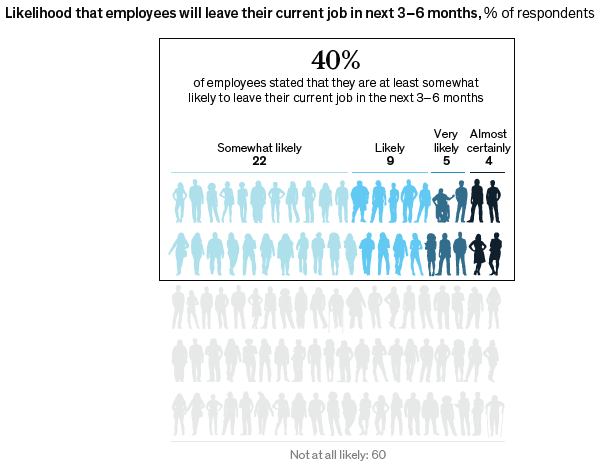

40% of the employees surveyed said they are at least somewhat likely to quit their current jobs in the next 3 to 6 months, where 18% say this is almost certain.

Chart 1:

Source: McKinsey Quarterly

You may look at the above graphic and think it’s great that at least 60% of employees are unlikely to leave, but that would be too optimistic an outlook, where if 22-40% of your workforce left, companies would be unable to operate certain aspects of their business or would be at risk of problems occurring.

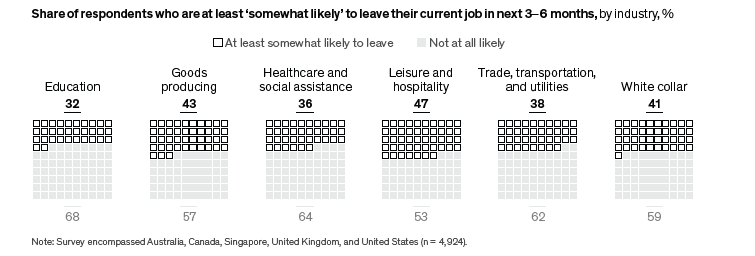

This circumstance is not concentrated on any one industry either, no, this was broadly consistent across the five nations surveyed and across multiple industries as well.

The fact that this average was in line with the white-collar industry average – the majority of this note’s audience – should be deeply concerning.

Chart 2:

Source: McKinsey Quarterly

Attrition Getting Worse

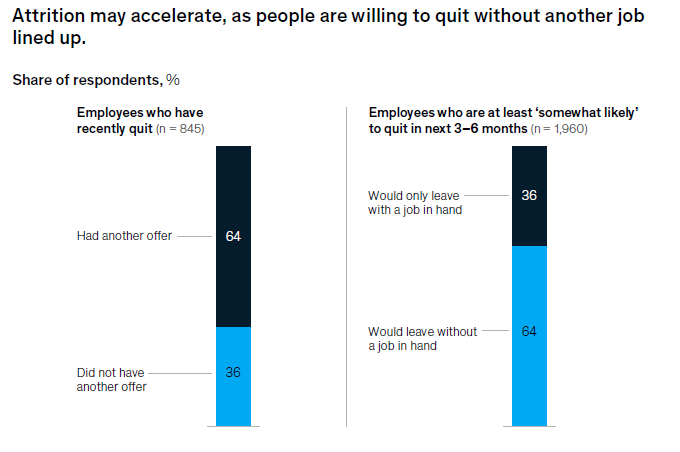

One section of the report that drew my eye was that for employees who had quit their jobs in the past six months, did so without having a new job lined up.

36% of those quitters reported leaving in that manner, highlighting another way the “Great Attrition” differs in structure from other post-recession recovery cycles.

It also shows how employers are unlikely to be aware of employee concerns, and how hard the 18-20 months since the pandemic began, have been.

Chart 3:

Source: McKinsey Quarterly

Changing Attraction

Another trend that’s emerging – one we’re all fairly well aware of – is the growing trend towards flexible work patterns, where someone may not only seek to work 1-4 days a week instead of the more regular 5 days, but they may only wish to work in an office environment for a portion of those days, opting to work from home the other days.

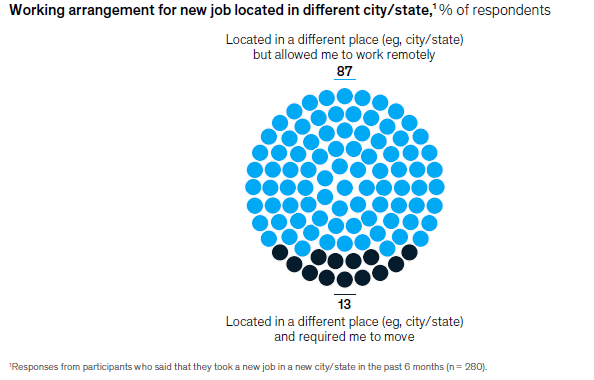

This level of flexibility is enticing even the 60% of people who hadn’t been considering leaving their current employer, where 65% of the survey said they didn’t leave their job because it was in a location that they want to live.

Of note, those who left their jobs and took jobs in new cities, 90% of them didn’t need to relocate as they were allowed to work remotely.

This is the formation of a concept called “location agnostic” employment, which may prompt satisfied workers to start guessing their commitment to companies where they work now, if management mishandle the transition to a hybrid-work environment.

As a simple thought experiment for people that live in expensive cities (relative to median income) such as Sydney or Melbourne:

If you were paid a similar wage to work a similar job, but could work remotely and not need to be located in Sydney/Melbourne/etc, would you live elsewhere?

While the answer will differ person to person, there will be a large portion of people happy to live in cheaper destinations where housing is more affordable, but still within proximity to friends and family and airports.

Chart 4:

Source: McKinsey Quarterly

Employers and Employees Understanding One Another

When employers were asked why their employees quit, they cited:

- Compensation

- Work-life balance

- Poor physical or emotional health

However, when employees were asked why they left, they said:

- Didn’t feel valued by their company

- Didn’t feel valued by their manager

- Didn’t feel a sense of belonging at work (alignment with culture or company’s goals)

While the employers were correct that those reasons were important, they simply weren’t as important as the reasons the employees cited.

Attrition vs. Attraction

In much of Australia, we’re hitting our 70 and 80% 16+ vaccination thresholds and seeing borders open to both domestic and international travel.

With this, comes the ability for more and more white-collar workers to return to office locations.

However, McKinsey warns against “heavy-handed back-to-the-office” policies or mandates, as “no matter how well intentioned – are likely to backfire.”

They encourage managers to think through and consider their next moves, and to include employees in the decision-making process.

Where they plainly state:

“…executives aren’t listening to their people nearly enough. Don’t be one of these executives.”

Questions to Ask Ourselves

- Do we shelter toxic leaders?

Managers that don’t make people feel valued drive them from companies, with or without a job in hand.

- Do we have the right people in the right places?

Employers found that they had the right people, but not necessarily in the right places. This was damaging in hybrid-environments where new types of leadership skills were required.

- How strong was workplace culture before the pandemic?

You may see a return to work as a method to address cultural issues that may have been pre or post-COVID or prefer a return to work as you may have missed it. It’s important to realise that your company’s culture may have changed over the past 20 months, and your employees may not miss it nearly as much as you do.

- Are benefits aligned with employee priorities?

Within the McKinsey survey respondents, 45% cited the need to take care of family as an influential factor, where a similar amount who were thinking of quitting were thinking this for the same reason.

Allowing more flexible work arrangements, WFH arrangements, and understanding the needs for childcare, nursing and other family-focused benefits could help stem the attrition of workers from workplaces.

- Are you providing career paths and development opportunities?

This one speaks for itself. If employees are leaving and thinking of leaving because they don’t feel valued, they’re finding or waiting for other employers to do so instead.

- Are we building a sense of community?

Although McKinsey cite that remote work is not a cure for cultural issues, neither is a full in-office return policy which may ostracise many workers who feel aggrieved by the heavy-handed approach or lack of consultation.

For example, employees with unvaccinated children may feel unsafe returning to workplaces or in-person gatherings.

There are many ways a company can retain (or establish a new) culture, even when not all working in the same office space.

Closing Remarks

I’d fully encourage anyone to read the full McKinsey report that I hyperlinked at the start of the note, as it provides many keen insights into the shifting labour market behaviours evident across Australia, the USA, UK, Singapore and Canada.

While this doesn’t present a specific investment thesis or actionable investment idea, it’s an emerging trend still in its infancy that will ultimately shape company’s growth trajectories.

Companies that get this wrong will experience further or new employee turnover, and likely underperform companies that get this right and retain talent.

The views expressed in this article are the views of the stated author as at the date published and are subject to change based on markets and other conditions. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Mason Stevens is only providing general advice in providing this information. You should consider this information, along with all your other investments and strategies when assessing the appropriateness of the information to your individual circumstances. Mason Stevens and its associates and their respective directors and other staff each declare that they may hold interests in securities and/or earn fees or other benefits from transactions arising as a result of information contained in this article.