The collapse of the Terra/Luna ecosystem has been a stain on the cryptocurrency industry for the past few weeks – supporting the arguments of many sceptics who talk of tulips, bubbles and the need for harsh and sweeping regulation.

For many, this collapse came as no surprise, where industry participants had continually pointed out the vulnerabilities within Terra’s self-perpetuating ecosystem.

Its tribalistic and fanatical investor base was ultimately a core component of its demise – where rapid growth in the ecosystem ultimately forced it into a “death spiral”, erasing approximately $60 billion USD of value in a matter of days from the savings of vulnerable retail investors, and causing the downfall of many related funds and products.

Whilst the true value lost from this failed experiment will likely exceed far more than $60 billion through its implications for related protocols and the inevitable imposition of more prescriptive regulatory action, its longer-term implications will likely be minimal – where harsh losses and steep learning curves are merely a product of an industry innovating at warp speed.

Stablecoins have played and will continue to play a vital role in the development of our digital economies – where their form and structure should evolve to provide more economically efficient structures over time.

What this calamity did manage to promote is a deeper discussion on stablecoins, where we’ve been able to better define their purpose, and what models will likely succeed in the future.

So, as the topic of today’s note, we will discuss stablecoins – how they can operate and what promise they possess.

There’s More Than One Way to Skin a Cat

Stablecoins have played a key role in the meteoric rise of the cryptocurrency industry, bringing together the stability of fiat currencies, and the efficiency and composability of blockchains.

They have acted as a gateway into the cryptocurrency world, enabling investors to seek the safety of fiat currencies, whilst still remaining able to invest and send funds around the world, at the click of a finger, 24/7, 365 days of the year.

Contrary to what the uninitiated may believe, there are multiple different ways in which stablecoins can operate, with each structure having its advantages and disadvantages.

Fiat Pegged Stablecoins

Fiat pegged stablecoins are the most utilised structure, pegging themselves to a fiat currency (usually USD) through being backed 1:1 by fiat assets held by a financial institution.

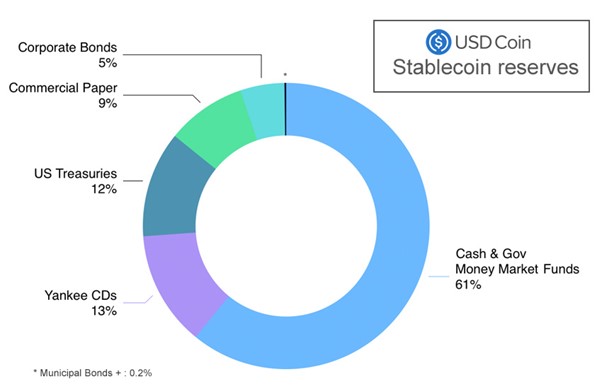

These fiat assets are usually made up of a carefully constructed mix of cash, commercial papers, treasury notes, certificates of deposit and corporate bonds.

The assets selected are those which are as close to “risk-free” as possible, given a purely cash-based reserve would be unable to generate the yield required to maintain the operations of a stablecoin – much like how it would be unprofitable for banks to operate without utilising the fractional reserve system.

Source: Circle

The 3 most prominent fiat stablecoins, Tether (UST), USD Coin (USDC) and Binance USD (BUSD) have an approximate valuation of $145 billion USD as of the writing of this note and play a key role in forming the foundations of the cryptocurrency industry.

Whilst Tether has had it fair share of controversies, given its lack of disclosure into the composition of its reserves – where some feared it held Evergrande commercial papers – USDC serves as a leading example of what fiat-backed stablecoins should look like, with regular attestations from Grant Thornton, and transparency into the composition of its reserves.

Though this model may seem sustainable now, there are two constraints which will force the industry to move in a different direction over the long term.

The first is capacity constraints – current models operate around the custodianship provided by financial institutions, who take no fee for holding billions of dollars in liquid assets. Such a model works when the quantum is in the realm of a few hundred billion dollars, but when reserves reach the trillions, our view is that it is unlikely that the banks will continue on with this arrangement. Moreover, should the value of the cryptocurrency ecosystem surpass that of the traditional financial world, there won’t be a sufficient amount of liquid assets on hand to maintain these pegs – though such an occurrence is far down the road and only a concern in the bull case for cryptocurrencies.

The second is regulatory barriers – when Facebook’s Diem stablecoin came to market, the Federal Reserve prohibited SIlvergate bank from being the warehouse, given the launch would’ve likely made Diem one of the largest circulating currencies. This would’ve placed Facebook in direct competition with various bank rail-enabled fiat currencies who are incentivised to lobby against such a move.

Therefore, we can see that whilst fiat pegged stablecoins are currently a prudent and efficient means of transferring capital via blockchains, it’s impossible for them to act as the primary form of stablecoin over longer-term horizons, and in an absolute bull case.

Over-Collateralised Stablecoins

Over-collateralised stablecoins enable cryptocurrency users to mint fiat pegged tokens, in exchange for crypto collateral. Given its separation from traditional financial markets and its support of the decentralisation ethos, our view is that such a model could be more sustainable over the longer term.

The most successful over-collateralised stablecoin is MakerDAO, which enables the creation of DAI (where 1 DAI=1 USD), through the pledging of crypto collateral on the Ethereum network.

This collateral ratio is set at 150%, so if I had $1 worth of ETH, I’d be able to lock up this amount, and mint 0.66 worth of DAI.

Should the value of the underlying collateral decline below this 150% collateralisation ratio, Maker will programmatically liquidate said collateral through the Ethereum blockchain to maintain the value of the “loaned” DAI.

The one pitfall of such a system is the removal of liquidity from the cryptocurrency ecosystem upon the process of minting the DAI.

When taken to its limits, it could completely drain liquidity and collateral from the entire ecosystem, making such a model unsustainable to act as the only form of stablecoin.

This differs from what you would see in a fractional banking system, which enables the exponential growth of capital without a material draining of liquidity.

Algorithmic Stablecoins

Algorithmic stablecoins attempt to remove any link to “hard collateral”, overcoming the capacity constraints of fiat pegged stablecoins, and the liquidity draining properties of over-collateralised stablecoins.

They have long been touted as the ‘end state’ of stablecoins, though none have yet built a model which has stood the test of time.

They operate through creating a self-equilibrating ecosystem, where Terra has stood as the most infamous example.

In Terra’s case, UST served as the stablecoin, whilst LUNA, the governance token, acted as the balancing weight which maintained a peg to USD.

The peg was intended to be maintained through the ability of investors to burn (exchange) 1 USD worth of LUNA for 1 UST.

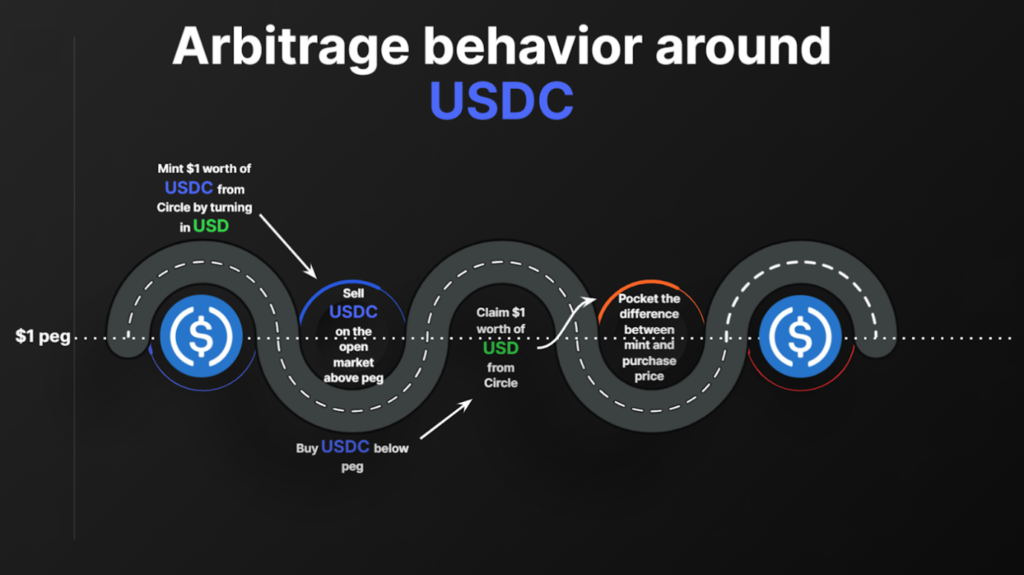

If UST = 1.01 USD, then investors were incentivised to arbitrage this difference, by burning their $1 worth of LUNA, minting 1 UST and selling this for $1.01.

Likewise, should UST = 0.99 USD, then UST holders could burn 1 UST (worth 0.99) and mint 1 USD worth of LUNA, and profit through then selling this LUNA for $1.

Source: TheTie Labs

This system was self-referencing, and highly reflexive – more minting of UST increased LUNA prices (through removing supply of LUNA) – and as the LUNA price got higher, the more UST could be minted.

This peg was maintained for some time, though its downfall (like many before it) was through the demand of the underlying governance token and the level of confidence in the system.

We can see the value of demand and confidence through our own traditional fractional reserve banking systems, where bank runs are rare, despite them only keeping a fraction of our deposited funds on hand.

We choose to hold our money with banks, despite them only keeping a fraction of deposited funds on hand, because of our confidence in the ability of banks to continue to accrue value over long periods of time, and due to any implicit/explicit government guarantees on our savings.

In the LUNA ecosystem, we saw a “death spiral”, where a complete loss in confidence occurred in the ability of UST to regain its peg, given insufficient levels of demand for LUNA (where demand would incentivise investors to backstop the value of UST), and the lack of any reserves or centralised figures able to backstop the collapse. Effectively, this was the digital asset form of a “bank run”.

The same reflexivity which enabled the ecosystem to grow at breakneck speed was the same which drove it to 0 in a matter of days.

Should the LUNA ecosystem had been a strong source of value accretion and had the market capitalisation of UST been smaller, relative to LUNA, we may have seen greater confidence from investors in the restoration of the peg, given participants in the LUNA ecosystem would have been more incentivised to retain the peg.

Given algorithmic stablecoins offer the key to an exponentially growing stablecoin market, it is inevitable that we will continue to see developers building new and improved models – though what a successful model will look like is still unknown.

What Next?

In our view, stablecoins have been the most efficient and effective means of storing value within the cryptocurrency ecosystem, and will likely continue to be the backbone of a growing crypto economy.

Their ability to transfer wealth across ecosystems and geographies in a cost-effective and time-efficient manner will likely be unsurpassed by legacy financial systems for many years, and as a result, will continue to grow as their use cases expand.

Though in order for stablecoins and DeFi to truly become material inclusions within our global economies, regulatory guardrails must be implemented to prevent such events occurring again in the future.

In a best-case scenario, these guardrails would be self-governed to ensure the maintenance of decentralisation within the ecosystem.

Stablecoin issuers could look to the Basel Accords which were established post-GFC, as a framework which they could adopt when determining a set of minimum standards regarding the composition and level of liquidity within their reserves.

In a worst-case scenario, certain geographies will be restricted from using stablecoins – like what has been discussed in the EU.

As with all new technologies, regulators will need to strike a balance between protecting investors, and promoting innovation – as after all, all innovation comes at a cost.

The views expressed in this article are the views of the stated author as at the date published and are subject to change based on markets and other conditions. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Mason Stevens is only providing general advice in providing this information. You should consider this information, along with all your other investments and strategies when assessing the appropriateness of the information to your individual circumstances. Mason Stevens and its associates and their respective directors and other staff each declare that they may hold interests in securities and/or earn fees or other benefits from transactions arising as a result of information contained in this article.