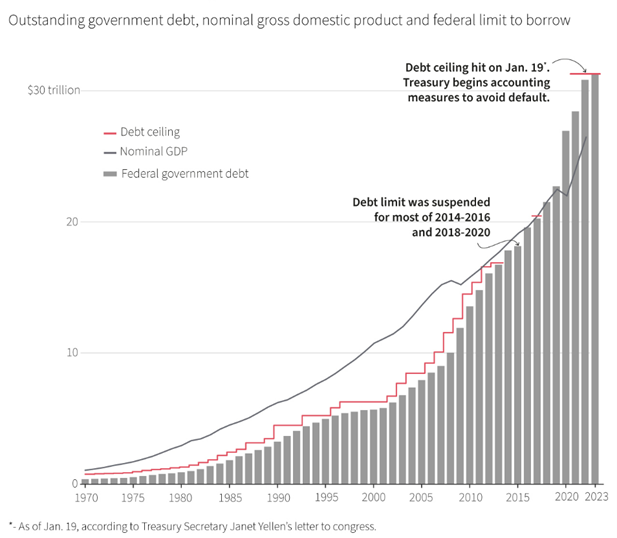

The United States of America running at high levels of debt is nothing new, however COVID related fiscal policy has seen this balloon in the past few years to be at 123.6% of Nominal GDP (Sept 2022).

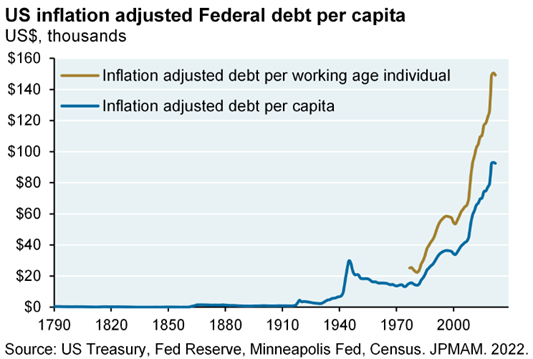

The chart below shows the spike from government spending after WWII and the struggle to reduce the deficit since then. The inflation adjusted debt per capita is now three times that amount.

Interest rates have also increased significantly over 2022, which increased the costs of new issuance to service this debt. Because of these and other contributing factors, the US has now reached their current debt limit and have just announced they need to start using extraordinary measures to avoid breaching the debt limit or risk defaulting on their debt.

What is a debt limit?

The definition of the debt limit from the US Treasury department is “the total amount of money that the United States government is authorized to borrow to meet its existing legal obligations, including Social Security and Medicare benefits, military salaries, interest on the national debt, tax refunds, and other payments.”

Reaching the debt limit and failing to increase it could cause the US government to default on its debt.

Since 1960 this limit has been reached 78 times, requiring action to be taken to avoid this limit from being breached. The current limit sits at $31.4 trillion.

The limit has also been suspended several times since this approach was first taken in 2013, but the Republicans have historically been less inclined to allow this then the Democrats.

Source: Reuters

Janet Yellen announced that the government would start using extraordinary measures from January 19 to avoid reaching the debt limit. These are accounting manoeuvres involving shifting money between government accounts.

This will allow the Treasury to continue the issuance of bonds and repaying bondholders, but it is forecast to run out between June and August.

What happens next?

It is not expected that this issue will be resolved with ease or swiftness, and rather be used as leverage by the Republicans in negotiations between the two political parties.

The Democrats are after a clean debt ceiling increase, but the Republicans want to use this leverage to exact spending concessions.

There is also a possibility for Congress to pass one or multiple short-term extensions which could see this crisis continue over many months this year. This could be used to push the extension to September 30 to coincide with a new fiscal spending year and maximise the pressure for budget cuts.

We could also see a government shutdown this year as a result of an agreement on the debt limit not being reached.

The last time the debt crisis occurred was 2011 and saw the introduction of the Budget Control Act with the Democrats agreeing to budget cuts across the board to get the debt ceiling increased from $14.3 trillion to $16.4 trillion.

This debt crisis however lead the S&P to downgrade the US credit rating from AAA to AA+ as it came so close to defaulting.

It currently sits at this same rating as it has not recovered its AAA rating. This period also saw a significant sell off in US equities as a result. The S&P500 fell 15% in 10 days after the deadline.

What are the risks?

While the risks of a default are low, we will likely see a great period of uncertainty in markets over this period.

Adding volatility to this situation is the fact that the Republicans have only a small majority in the House of Representatives, and the struggles that Kevin McCarthy faced to be voted in as Speaker.

This may make negotiations between the two parties more difficult as individuals take the opportunity to push special interests.

The biggest effect would be felt by stocks closely tied to government spending, notable the defence sector and healthcare.

If a debt limit was breached, this would see a sell off in equity markets and greatly increase the chance of a recession.

A warning sign of an increased threat of default would be if the 6-month Treasuries got cheaper.

Of some relief is that we are coming up to March 15 which is the deadline for US corporate tax returns. This should provide a boost to the Treasury’s cash balances.

What this means for the bond market

The US government is the largest issuer of debt globally with $30.9 Trillion worth of debt and the next closest is Japan at $15.231 Trillion. Because of the size of this debt and range of its holders, there are many investors affected by movements in Treasuries.

There are a number of interesting dynamics we may see here. One of these is that we may actually see a flattening in the US yield curve if there is a decrease in issuance of new debt. There was a rally in Treasuries in 2011 due to a perceived shortage of bonds.

The increased volatility that this crisis is having on the bond market currently is evident through looking at US 5yr CDS. The cost of insuring U.S. debt against default for five years is at the widest spread since 2013, currently at around 33bp.

Source: Bloomberg, Mason Stevens

An increase in default risk could lead investors to look elsewhere when investing as US Treasuries are seen as one of the lowest risk investments and so would be less fit for purpose.

We do not expect a US default and rather expect both the Democrats and Republicans to come to a compromise on either a permanent or temporary increase in the debt limit. The main threat to markets will be the uncertainty of when this will be resolved and will likely be amplified if this drags on for many months.

If somehow we did have a US default it would send shockwaves through the financial system and cause investors to reassess what is often the benchmark “risk-free” rate. The implications of this catastrophic event make its probability very low.

The views expressed in this article are the views of the stated author as at the date published and are subject to change based on markets and other conditions. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Mason Stevens is only providing general advice in providing this information. You should consider this information, along with all your other investments and strategies when assessing the appropriateness of the information to your individual circumstances. Mason Stevens and its associates and their respective directors and other staff each declare that they may hold interests in securities and/or earn fees or other benefits from transactions arising as a result of information contained in this article.