There are only two ways to size an investment.

The investment makes money and you invested too little, or the investment loses money and you invested too much.

My flippant oversimplification aside, sizing investments appropriately does have a fair amount of science to it, as it should, as investors buy and sell with expected returns and risks in mind.

The reason I’m writing about this today is that in recent reviews of platform client portfolios (mostly models managed on the platform), there was a trend towards manager’s holding smaller, often legacy positions within portfolios that were unaligned with their overarching strategies.

The underlying philosophy should be simple:

- Do you want XYZ position to have impact or not?

If you’re investing in a company or fund manager you expect to do tremendously well, then should it be input in a size that will allow it to add material value?

Conversely, if you’re not convicted in the outlook for a specific security, industry, market, asset class or fund manager, should the size of the position be diluted to have less relative impact, spreading risk and return across more sources.

Diversification vs Unification

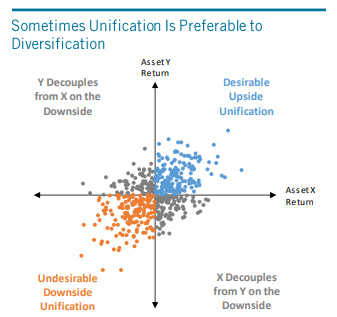

Diversification versus unification is a topic we haven’t written about since March 2021, where the crux is that return expectations tend to be elliptical, and the holy grail of portfolio construction is to achieve UPSIDE unification and DOWNSIDE diversification.

I.e. our portfolio’s assets all rally at the same time but become sparsely correlated in negative periods

Chart 1: Diversification Versus Unification in an Elliptical Return Distribution

Source: Kinlaw, Kritzman, Turkington, Page (2021)

What Does Impact Look Like?

Impact will mean something different to each investment portfolio or model portfolio, as it’s a relative term.

For example, a portfolio of 10 stocks alone is on average likely to be more closely correlated than a portfolio of 10 different securities or positions in 10 different asset classes.

That isn’t to say that more positions means more diversification, that’s erroneous logic.

More positions of similar or closely correlated assets are an example of unification, where the reasons for positive or negative performance are not dispersed.

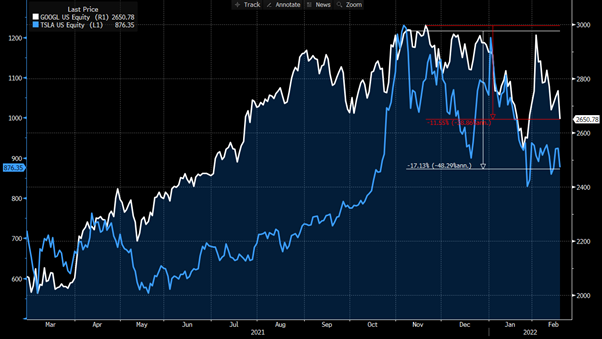

This again is complex, dynamic, and relative, as two stocks – for example Tesla and Google – may both rally in equity bull markets like they did in CY2021 and be considered correlated, but they did so for vastly different reasons, which is why they performed quite differently in the past 4 months.

Chart 2: Price Chart of Tesla (TSLA:NASDAQ) and Google (GOOGL:NASDAQ)

Source: Bloomberg, as at 18/Feb/2022

Impact is a portfolio manager’s assessment of the relative risk/reward for including each additional instrument in the portfolio, it’s likely reward and that impact on total performance.

Simply:

A 10% position within a portfolio that then rallies 10% provides a 1% total gain to the portfolio’s value.

It’s for this reason that including 2% or 3% positions in portfolios may be suitable, but if they’re your best ideas, a 10% or 20% rally in that security really doesn’t move the needle – returning 2.2 to 3.3% or 4.4 to 6.6% respectively.

On the flip side, a 6.6% total portfolio return may be exactly the impact you want, hence, it’s relative.

I saw this recently in a model manager’s portfolio where a high-conviction hedge fund was included in a portfolio at a ~2.5% position. Even if the hedge fund shot the lights out and returned 100% this year, this would only add 2.5% to total portfolio returns, whereas a 10% allocation was more plausible (for this portfolio).

Position Creep and Endowment Effect

This type of portfolio construction most often comes from two sources:

- Endowment Effect

- Position Creep

Endowment Effect is also being known as “married to your positions”, where the longer you hold a position the more you become psychologically attached to it and less likely to sell it, partially or totally.

Position creep occurs over time when existing positions are not sold as new ideas become acceptable and investible and may be diluted down to make way for new positions.

For example, you may construct your portfolio originally with 10 positions of 10% each.

Over time you like new ideas and rather than selling any of your first 10 positions – they may still be worthwhile in your view – you dilute some of the positions to add new positions.

You may end up with 20 positions of 5% allocation, where now the prospective risk-reward setup is completely different than compared to the 10% allocation, depending on your views of diversification vs unification, and your need for impact.

1/N

1/N is a portfolio construction theory that seeks to implement equally weighted portfolio positions consisting of N-number of positions.

e.g. 20 positions is 1/20 = 5% positions

It’s a concept that gained popularity in the past 30 years proposing that concentrated portfolios or unequally weighted portfolios were inferior to equally weighted portfolios.

Statistically, equally weighted portfolios should always outperform the worst-performing asset class/security/fund, and always allows some allocation for the best performing asset class/security/fund.

While I could spend 1000 words trying to refute 1/N being better than optimised portfolios – if you’re interested there’s lots of critiques of the most influential 1/N study by DeMiguel, Garlappi and Uppal (2009) – I’d rather summarise by saying many of us can do better than this in security specific portfolios, using SAA, TAA, DAA and also building direct-security portfolios.

Total Portfolio Analysis

In recent years, we’ve seen a ground swell of buy-side fund managers seeking total transparency into their portfolio allocations.

Until recently, you could invest in a (randomly chosen) PIMCO, Vanguard, or Platinum fund but had opaque transparency into the underlying components.

Sure, their monthly report may say their interest rate duration, top 10 holdings, number of holdings, weighted average credit rating etc, but that is quickly becoming not good enough, and we can definitely do better.

For example, we’re working with FactSet to get fund managers on our APL to share/upload their holdings each month, so that for a multi-asset portfolio, we can review every single position and know in much more granular detail our total portfolio positioning.

This approach will only become more and more popular to allow portfolio managers to accurately position portfolios for unification/diversification and to create impact.

In this case, we also use “impact” as word of multiple meanings, where this amount of transparency will be key for ESG integration, rather than fund managers or ETFs claiming ESG, now model managers will be able to craft portfolios that align with their own idiosyncratic needs.

On the topic, we ran this level of analysis for another model manager a year ago and in their case they owned 14 different managed funds and ETFs in this specific model, 4 of which were international equity funds.

What we found when running TPA was that this model manager had close to 1300 positions across the entire portfolio (a large majority of this was from fixed income securities where FI managers tend to hold more underlying positions), but of the ~250 international equity positions, each of their 4 international equity managers were most materially exposed to FAANG stocks plus Tencent and Alibaba.

In reality, they were paying management fees >1% p.a. and performance fees on top again, to own stocks they could easily purchase themselves in their model portfolios, where these managed funds had similar correlation coefficients and similar strategies.

Bingo, value added.

Closing Remarks

It’s important to review portfolios periodically and consistently to assess not just the risk/reward of your portfolio’s positions, but to assess the likely impact this risk/reward will have on purpose and if it suits your target return and other objectives.

You could have the best idea in the world that does 100%+ but might make no impact if the position is not sized appropriately to have impact.

Likewise, you may oversize a position and it has detrimental effect on total performance.

Bibliography:

DeMiguel V, Garlappi L, Uppal R (2009), “Optimal Versus Naive Diversification: How Inefficient is the 1/N Portfolio Strategy?”, The Society for Financial Studies, Oxford University

Turkington D, Kinlaw W, Kritzman M (2017), “A Practioners Guide to Asset Allocation”, Wiley, Boston, MA

Turkington D, Kinlaw W, Kritzman M, Page S (2021), “The Myth of Diversification Reconsidered”, MIT Sloan Research Paper No. 6257-21

The views expressed in this article are the views of the stated author as at the date published and are subject to change based on markets and other conditions. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Mason Stevens is only providing general advice in providing this information. You should consider this information, along with all your other investments and strategies when assessing the appropriateness of the information to your individual circumstances. Mason Stevens and its associates and their respective directors and other staff each declare that they may hold interests in securities and/or earn fees or other benefits from transactions arising as a result of information contained in this article.