Diversification is an investment process that seeks to lower portfolio risk in order to achieve a lower variability in returns.

The importance of diversification only started to be a mainstream economics concept in the 1950s, when Harry Markowitz wrote his PhD thesis on “Modern Portfolio Theory”, which was a concept so novel that his doctoral advisor and renowned economist, Milton Friedman, argued was so foreign as to be “not economics”.

Markowitz’s work extended the existing body of academic literature in optimal mean-variance portfolio construction, where practitioners seek to create the best risk-adjusted investment portfolios.

Fast forward to modern day and there have been contemporary adaptations to Modern Portfolio Theory and portfolio optimisation techniques.

In particular, the publication of “A Practioners Guide to Asset Allocation” in 2017 by MIT doctoral fellows David Turkington, Mark Kritzman and William Kinlaw caught my attention, a book that has become a bible of sorts for me, in investment management.

This brings us to 2021, where these three academics, along with co-author Sebastien Page from T.Rowe Price, have published a new body of academic literature that expunges specific diversification myths, and proposes a new way to optimise portfolios.

In particular, the paper addresses gaps in the academic literature in regard to asset class correlations, optimal portfolio construction and asymmetric return profiles of disparate investments.

You can access the paper here, where the paper was published under the Massachusetts Institute of Tech (MIT) Sloan School, known for their innovative financial services industry research.

Diversification Theory

We measure diversification through correlation coefficients: the degree to which two financial asset prices will deviate from one another. Basically, we measure the deviation in return profiles from Asset A to Asset B.

This is what Markowitz’ original work promoted to new significance in 1952 in construction of optimal portfolios given expected returns, risks and correlations.

Out of interest, these three factors became known as “Capital Market Assumptions” and are derived by institutional asset managers (including Mason Stevens) to construct bespoke portfolios for clients.

For example, the Portfolio Projections feature of our investment platform utilises these assumptions.

This means that 70 years after introduction, Markowitz’ work is robust and as relevant today as it was back then.

Upside Unification, Downside Diversification

The obvious issue with designing a portfolio that is truly diversified in returns is that you’ll have components that rally during bull market periods, that are offset by the diversified assets that sell-off at the same time.

This might stabilise returns, but is this optimal?

I’ve seen this strategy previously compared to trying to drive your car with the handbrake on.

A truly optimal portfolio seeks upside unification and downside diversification, a Holy Grail of sorts.

After all, the goal of investing is to retain and grow wealth, not to avoid correlation for the sake of it.

Designing Multi-Asset Portfolios

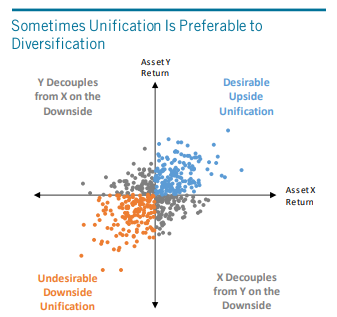

In the below simulation, the MIT academic team use Monte Carlo simulations to generate 500 returns for assets X and Y where asset X is the main growth driver and asset Y is the source of diversification.

When asset X performs well, we would want asset Y to also perform well.

However, when asset X performs poorly, we would want asset Y to perform well.

Basically, we would want the assets within our portfolio to be within the top right quadrant of this graphic and do not want assets in the bottom left quadrant.

Avoiding Unfavourable Downside

In normal market environments, fundamentals drive diversification of risk assets, but during pandemics and crises, investors “sell risk” irrespective of the fundamentals because of sentiment, a common factor in credit bond and equity correlations.

Meaning, markets tend to forget about the differences in default risk (equity more junior to debt), liquidity (debt generally more liquid than equity) and macro-economic variables (credit less sensitive to economic environment than equity), because these are long-form and rational ways to invest, and often foregone in a “sell risk” sentiment-driven market environment.

Related studies in psychology find that people react more strongly to bad news than good news, as fear is more contagious than optimism.

We see this every day in news headlines, where fear, greed and anger garner more attention than happiness, neutrality and stability.

Implications for Portfolio Construction

The team analyses several major asset classes:

- US equities

- Non-US equities

- Emerging Market equities

- US Treasury bonds

- US corporate bonds

- Commodities

They found that across these asset classes, at different points in time, they experience increasing co-variance.

Statistically, greater dispersion among correlations were found between the co-dependent asset classes.

Basically, the correlations changed dynamically over time, in reaction to market environments (fundamentalist vs sentiment-driven).

What you can do about this

The first method is to dynamically reallocate portfolios in anticipation of regime shifts, increasing exposure to safe-haven assets that offer downside protection and diversification, especially when expecting conditions to deteriorate.

This doesn’t sound difficult but the timing of dynamic asset allocation (DAA) is everything, as going underweight/overweight indices or benchmarks is a form of “variable beta”, a hedge fund strategy mostly utilised in equity markets to out-perform large benchmarks such as the NASDAQ or MSCI World Index.

As I mentioned, timing is everything and that potential source of out-performance can be a true source of under-performance if the dynamic allocation is early or incorrect.…which if you think about it are one and the same.

The second method is to place greater emphasis on downside correlations and capital preservation across the economic cycle when constructing portfolios, thereby creating a more strategic asset allocation (SAA) that is more resilient to downturns but possibly has less upside potential.

Said otherwise, investors using Method #1 are seeking to predict market conditions while investors using Method #2 are preparing, rather than predicting.

If you’re wondering which approach to use, you need to assess your optimal balance between your return objectives, your risk aversion and your investment time horizon.

I.e. your resilience to financial market storms and the utility you require during fair weather.

To close, this academic literature asserts that when predicting bullish market conditions and seeking upside unification, one should seek higher conviction strategies. When predicting bear markets, disperse and diverse strategies among defensive asset classes and different styles of management (passive/active/hedge fund etc).

The views expressed in this article are the views of the stated author as at the date published and are subject to change based on markets and other conditions. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Mason Stevens is only providing general advice in providing this information. You should consider this information, along with all your other investments and strategies when assessing the appropriateness of the information to your individual circumstances. Mason Stevens and its associates and their respective directors and other staff each declare that they may hold interests in securities and/or earn fees or other benefits from transactions arising as a result of information contained in this article.