Today I would like to take the opportunity to talk about Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), which is a recent socio-economic view stemming from the 1990s.

It may be surprising to know that MMT as a standalone concept was developed originally by Australian economist, Professor Bill Mitchell, as a development or extension of John Maynard Keynes work regarding monetarism.

Today, I am taking you on this journey into the world of arcane wizardry that is macro-economics because we are starting to practice MMT across the globe, whether knowingly or not.

With this practice comes consequences which we are better off being informed about – the positives, the negatives, the economic trade-offs etc so that we citizens and investors can better assess the outcomes.

What is MMT?

Modern Monetary Theory describes the use of government issued currency (fiat money), and the governments monopoly to issue this currency through a central banking institution. One of the core tenets is that employment is rarely at maximum levels, due to restricting the supply of financial assets (money) needed to pay taxes and satisfy savings desires.

i.e. By setting the cash rate too high through money supply manipulation, there is not enough money in private sector hands, to allow for maximisation of employment which is assumed to be the number one economic goal of society.

MMT espouses that a government could achieve full employment through creating new money to fund government purchases – i.e. creating money to fund budget deficits.

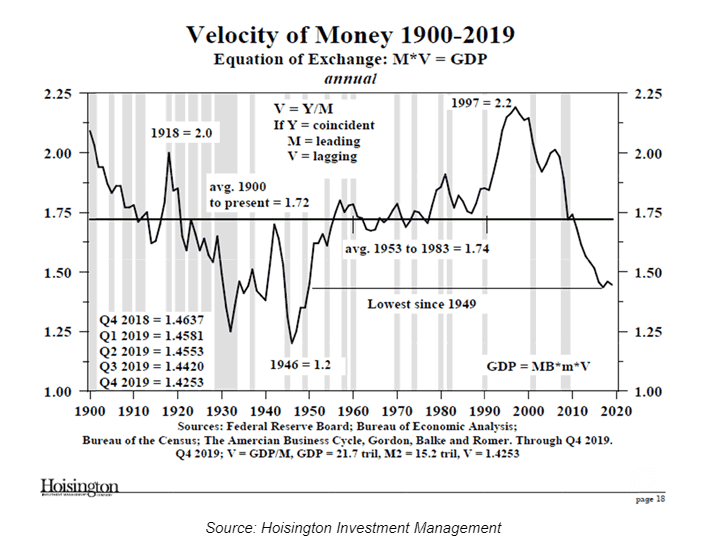

The primary risk of this is that once full employment is reached, there should be inflation, but that can be addressed by raising tax levels to flatten the inflation curve and reduce the velocity of money.

The velocity of money is another measure for economic output where

GDP = money supply * velocity of money

As I mentioned on Wednesday last week, the main tenets are:

- Government can pay for goods, services, and asset purchases without a need to collect more money from private citizens in the form of taxes or debt issuance

- Government cannot be forced to default on its own currency

- Government is only limited in how much money it can create by inflation and inflation expectations

- Inflation can be managed via taxation

- Therefore the private sector savings rate will be higher and thus consumption should be higher due to more money being available and create a larger velocity of money.

MMT in the year 2020

Governments around the world are using fiscal budget deficits to fund stimulus packages to support economies whilst COVID-19 disrupts industries and causes massive unemployment.

However, the spending that is being transacted is so large that it is going to be hard to pay for it in the short and long term.

Take the USA case for example, before the crisis their budget deficit was $1.9trn USD or 5% of their economic output (GDP). Since the crisis unfolded, they have approved another 2.2trn of spending with another $2trn proposed for infrastructure and jobs – not to mention that the initial 2.2trn will likely be not enough if lockdowns don’t end by early May. Combined we’re now around 6.trn deficit and that’s not counting what their central banks is spending in their QE program.

Add to the above figures that it’s an election year which usually adds more “promises”, and if the government can spend $2trn USD bailing out the private sector, I can foresee a policy initiative to payoff student loans of roughly another $1.6trn.

To put this in perspective, if you taxed every American worker at 100% of their income, this would not pay off the additional spending ~6trn USD of spending, let alone the existing budgetary gap.

I am also interested to see how the US treasury is going to sell $6trn of treasury bonds in a short period of time and how the market is going to digest this deluge of supply.

If the bond market reacts poorly, it is likely the Fed will use a technique known as “capping yields”, which they last did under President Roosevelt when the US government ran large deficits to rebuild and re-employ large masses of Americans.

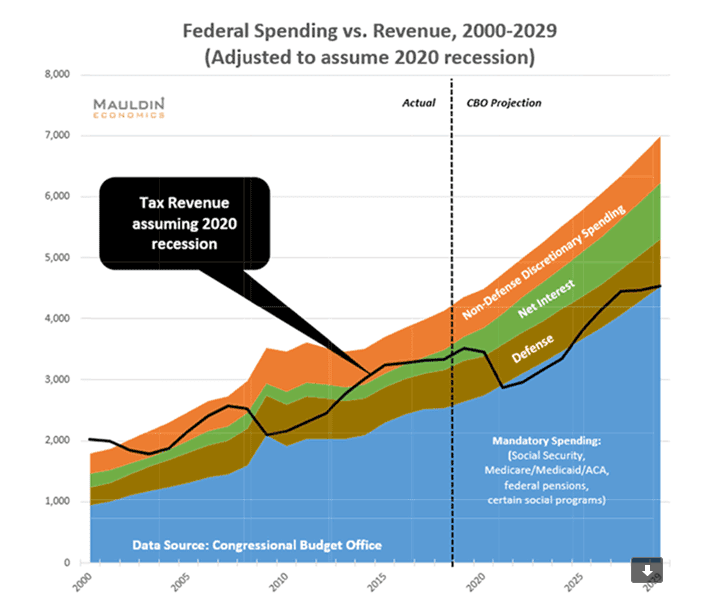

The below was a projection for the next 10 years of US budgets forecasting a 2trn deficit in case of 2020 recession. Well it’s going to be 4-6trn in reality with another 3.3trn of state and municipal budget deficits. This means the total US government debt will be closer to $50trn by 2030.

MMT in practice

What we are running into now is MMT in practice, whether it is intended or not.

If the private market can’t absorb the bond supply from the US – and remember it’s also Japan, Australia, the EU, UK, China etc all at the same time – and the yields skyrocket in order for investors to be compensated for their scarce savings, then this is when central banks will “cap yields”.

We are already doing so in Australia, with the RBA maintaining an unlimited bid for 3y Australian government bonds at 0.25%, effectively capping our yield curve in the short term. They could also attach target yields to cap the 10y or 20y government bonds as well.

This is more or less what is described by MMT.

Each country’s treasury department issues more bonds to fund the government spending, and the central bank buys the bonds by issuing more currency.

Having your cake and eating it too

I am critical of MMT as dismisses basis economic trade-offs.

Under the normal reality you can either have your savings and wages or you could have your Medicare, but you can’t have your Medicare but not fund it.

However, under MMT, you can have your Medicare and the government funds it.

What MMT does not cover for me is the diminished purchasing power of your dollars by increasing the supply of the money so drastically.

What I also worry about are tax rates.

Tax rates are usually set at optimal levels where too low = not enough revenue, and too high = corporations and HNW individuals find ways to avoid paying these taxes.

This is why taxation revenue in Australia has been roughly the same weighting of GDP, over the last 30 years.

Investment outcomes

I wish to note here that the below is moving into forecasting and involves a large array of unknown variables. Investors always need be nimble and able to change their minds at the drop of a hat. As always, I advocate not fighting central banks as their “bazookas” are overwhelming.

This will depend what MMT outcome you see.

If MMT causes inflation or the thought of MMT raises inflation expectations:

We have an anchored price of money, where the central bank is keeping the cash rate low (capping yields) and potential inflation starting to move asset prices higher – remembering that higher inflation compounds longer term interest rates. The likely scenario is that longer term interest rates if free to do so would move higher, causing a steeper yield curve. Assets that appreciate from inflation expectations (commodities, property, REITS etc) also should perform well here – all else remaining equal.

And if MMT does not cause the inflation outcomes above:

Then it will likely be a very flat yield curve where the price of money is depressed, and long-term investment is not compensated too differently from short-term investments.

At which, the discounting rates for equity ownership (private and public) should see higher price multiples applied, due to lower risk-free rates and an even longer “lower for longer” scenario.

Yield producing assets with set running yields will be more in vogue, whether they are credit bonds, loan funds, toll roads and other infrastructure assets.

The views expressed in this article are the views of the stated author as at the date published and are subject to change based on markets and other conditions. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Mason Stevens is only providing general advice in providing this information. You should consider this information, along with all your other investments and strategies when assessing the appropriateness of the information to your individual circumstances. Mason Stevens and its associates and their respective directors and other staff each declare that they may hold interests in securities and/or earn fees or other benefits from transactions arising as a result of information contained in this article.