The price of goods, services and financial assets determine our ability to consume or invest in them.

If prices increase and our income does not, then we need to reduce our ability to consume or invest.

In terms of goods and services, an increase in prices without a corresponding increase in income or wages is considered a deterioration in our standard of living.

This is why I was incredulous in late August when the US Federal Reserve changed their inflation targeting regime to an “average” inflation target.

When a central banker says they want to see higher inflation, they are generally saying they want to see higher costs of living.

Of course, a central banker will say they also want to see an offsetting increase in wages and income, however, that is often not the case nor is it a part of major central bank policy objectives.

Falling Short of Target

The Fed changed their goalposts because they were continually underperforming their objectives.

They were underperforming because of debt, deflation and demographic factors (the 3 Ds) that are more powerful than the central bank’s ability to create economic incentives to consume and invest through the manipulation of cash rates and bond yields.

In 2020, this manifests in central banks foreseeing a colossal demand gap, otherwise known as a deflationary gap, where demand is at levels below available supply.

In particular, this deflationary gap is the forecast difference between potential economic output and actual output.

This lack of demand is due to a global pandemic that has restricted the supply of goods and services across national and state borders, but also due to the resulting uncertainty of future personal and business activities, and the result is a lack of spending, or saving of income.

In the 1974 recession in the US, the output gap was 4.8%.

In 1982 the output gap was 7.9%.

And in 2009 the output gap was 6.4%.

In the case of the 2007/2008 GFC, it took the period 2009-2018 for the output gap to be closed, where actual GDP finally reached potential output as measured in 2009, nine years later.

And this was before debt/GDP exploded as they have this year.

For this reason, it’s hard to forecast inflation to exceed central bank targets of ~2-3% p.a.

More on inflation

If inflation is the prime ordinance that determines whether we invest or not – i.e. will we receive a real (after inflation) rate of return – then potential or lack of potential inflation should be one of our most important views.

Using the 3 Ds framework of debt, deflation and demographics, we can see that we have deflation ahead of us, not inflation.

It’s unlikely we return to 2019 levels of economic output, for some years, let alone reach what would have been our potential economic output (think 5 to 10 years or more from now).

Reasons for Inflation Deflation

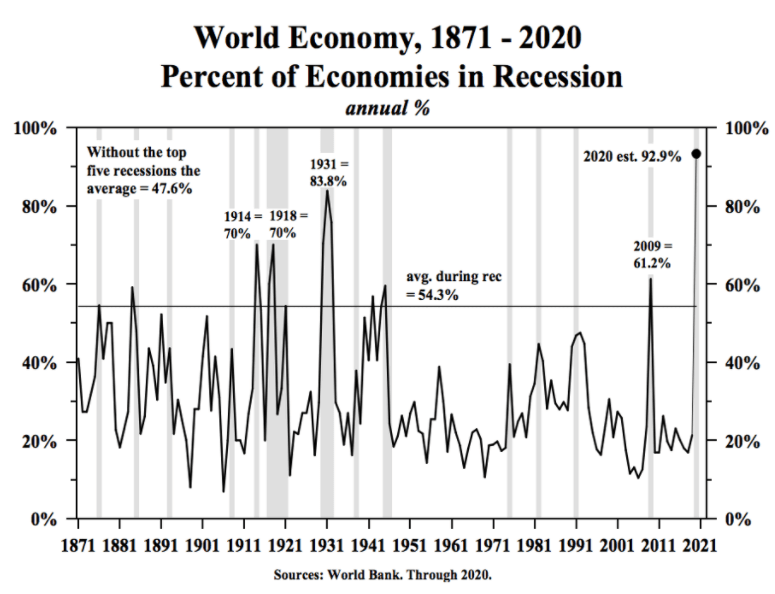

We will continue to have sub-par economic performance because COVID-19 is affecting the world’s economies at the same time, and there has been no precedent for this recession’s synchronicity.

At present over 90% of the world’s economies are contracting, therefore, no region or country is available to support or offset the contracting economies, nor lead a powerful sustained recovery.

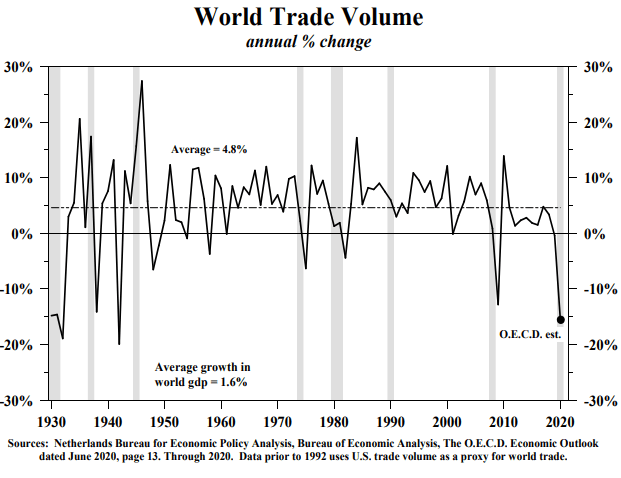

This also coincides with a global slump in trade volumes.

Export/Import trade volumes are one of the largest historical contributors to advancing global economic growth and are in the highly atypical position of detracting from growth as countries disagree over trade.

This is short to medium term deflationary, though can become inflationary when supply chains need to reconfigure, and a reduction in available supply causes prices to rise. However, in the short term, COVID has seen a reduction in aggregate demand.

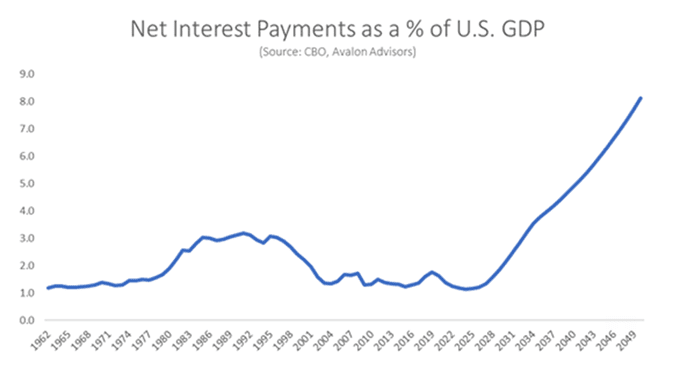

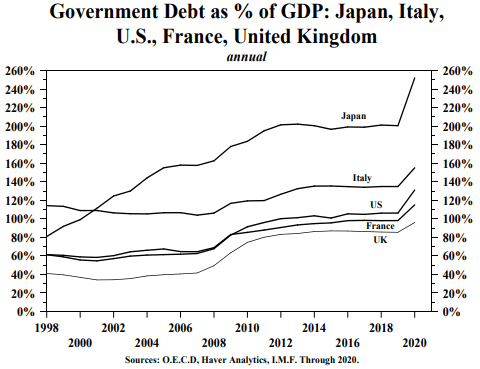

Furthermore, the debt incurred by most countries and many private entities, raised to mitigate the worst consequences of the pandemic have moved debt/GDP ratios into higher, uncharted territory. While this accumulation of debt has been for humanitarian purposes and in the case of sovereign debt, politically popular, this continues the persistent misallocation of capital to be reinforced, as productive resources needed for sustained growth will be unavailable, as they are allocated to unproductive debt.

Source: Mauldin Economics

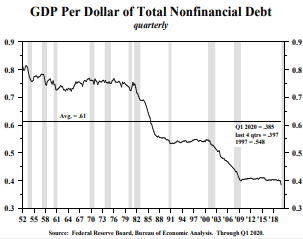

At this point I wish to mention that debt isn’t itself a problem if it’s sustainable.

Debt can be used for productivity enhancements, where for each dollar of debt, the liability creates a positive multiplier effect.

The problem is that each new incremental dollar of debt is not creating at least $1 or more of return, it’s taking $2-3 of debt to create $1 of value.

Key takeaways

As the pandemic eventually subsides, economies will register a noticeable rebound as growth rates bounce off a low base.

This is not to be confused with a return to pre-COVID levels of output and employment – something that will take many years to happen.

The consequences of the current debt binge will remain for years as there already is a “debt overhang” from previous years of borrowing, which will stymie potential growth.

As such, our global deflationary gap will remain for even longer – think 5 to 15 years – where actual output continually lags potential output.

Economists such as Irving Fisher, Charles Kindleberger and Hyman Minsky (Minsky is a favourite of mine) have long encapsulated the doubled-edged nature of debt; increasing spending now in exchange for a decline in future spending unless the debt generates income streams to repay principal and interest.

As the current debt incursion does not generate income streams that cover the P+I, the aggregate amount of debt becomes less and less manageable.

There is a significant body of research, particularly from the IMF and World Bank, that highlights the deleterious effects of high debt levels on economic growth, which starts from levels as low as 67% gross debt to GDP.

At current reading, the US has surpassed 120% and Australia is around 40%, though projected by Treasury to surpass 67% in financial year 2023/24.

All-in-all, the combination and synchronicity of all these factors can easily cause aggregate price levels to drop, thus putting downward pressure on inflation (short and long term), and likely weighing on bond yields further (yields down, prices up).

Final Remarks

The volume of debt has grown so large that only a sustained period of productivity led growth will allow for the debt burden to become less, as a portion of income or economic output. Productivity is required to grow at a pace that allows nations to escape the debt trap that will be with us for years and decades into the future.

Finally, this is why last week’s Federal Budget was disappointing as it was absent of major productivity reforms or funding that will enable Australia to grow and innovate, and meaningfully paydown debt through growth, rather than future cost reductions.

The views expressed in this article are the views of the stated author as at the date published and are subject to change based on markets and other conditions. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Mason Stevens is only providing general advice in providing this information. You should consider this information, along with all your other investments and strategies when assessing the appropriateness of the information to your individual circumstances. Mason Stevens and its associates and their respective directors and other staff each declare that they may hold interests in securities and/or earn fees or other benefits from transactions arising as a result of information contained in this article.