In the background behind any cyclical, short-medium term investment analysis are structural factors influencing a myriad of macro-economic variables, which affect portfolio returns.

One such structural force that I tend to focus on is demographics, writing notes such as “Demographics are Destiny” on 10th of Feb.

I’m writing about it again as data points from the end of December are now available, which show how global nation states have reacted to COVID-19 and how the pandemic has affected geopolitics.

A country’s demographics dictate its socio-economic model, and through that affect its relationship to other countries in the global economy.

A country with an older population translates into more retirees and fewer workers, a relationship labelled “dependency ratio”.

For example, in this relationship the dependency ratio would increase, as there’s more retirees dependent on the now diminished pool of workers.

Retiree Spending Habits

When people retire, they typically consume less.

As a larger share of the population transitions from work to retirement, the burden on society grows, as there are relatively fewer workers contributing to the welfare systems of the nation (unemployment benefits, pension systems etc.). This not only exacerbates the labour force further, but also diverts resources from other industries into occupations to care for the elderly – generally not high on productivity rankings relative to science, technology, engineering or mathematic (STEM) jobs.

On a national scale, this shift in favour of retirees over workers means:

- private consumption-led economic growth must give way to investment-led or export-led models of growth

- participation in equity and growth asset markets drops relative to fixed income and cash (defensive) assets

- increases in private investment translate to higher economic output (GDP) but if consumption is declining, then the added output must be exported to nations with insufficient domestic resources

- this also requires the nation to have cordial relationships with trading partners to allow this flow of capital from the domestic economy to the international economy

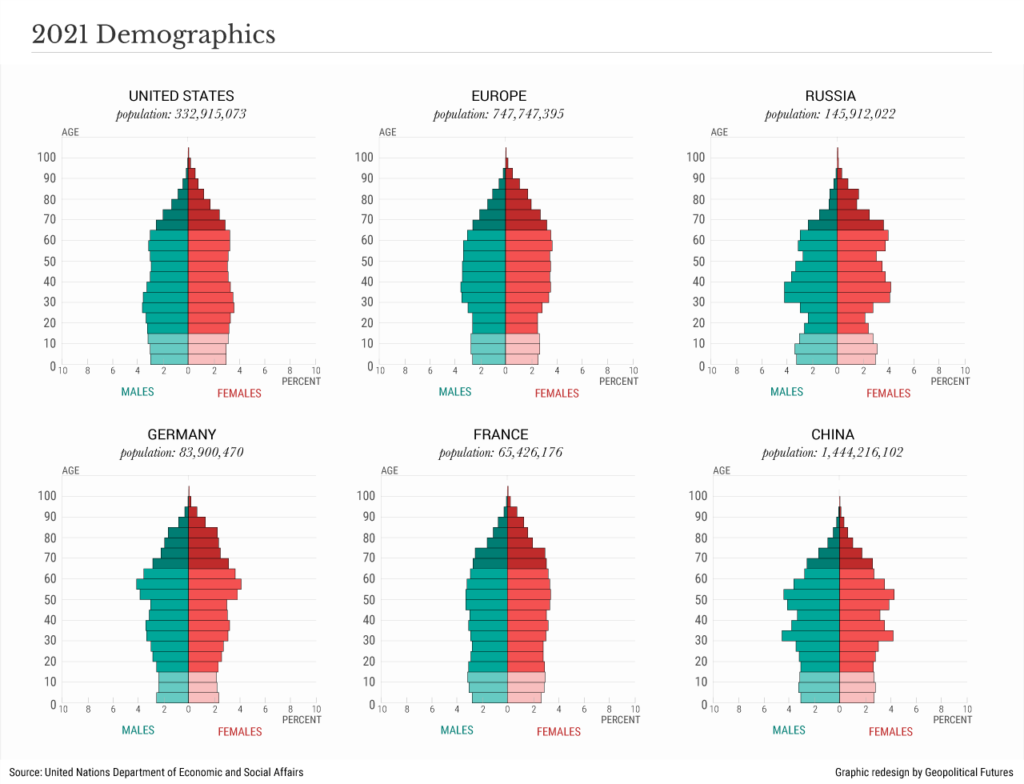

2021 Demographic Examples

Take Germany for example, where 28.6% of the German population is over the age of 60.

The less Germans consume, the more they must export as a share of the economic output (already high).

At the same time, the shrinking labour supply compels Germany to invest in European supply chains to support its export industries.

This works as long as there’s no economic crisis – or pandemic – and as long as demographics remain stable (i.e. balanced).

This balance has been closely and periodically reviewed in German parliament since 2008, as nationalists ferociously defend their export market and production network, under the European Union. To an extent, European Central Bank (ECB) policy has supported this through continued dovish monetary policies such as their cash rate at -0.60% and high levels of quantitative easing (asset purchases). This has synthetically caused EUR to remain low against CHF, USD, GBP etc, i.e. its close trading partners.

Germany has sought alternative export markets to Asia, because US demand was increasing at diminished rates, and also amid improved relations with China.

They also amended their immigration policy to be more friendly to workers with expertise and willingness to work in their manufacturing sector, thereby supporting their export power.

When the refugee crisis hit in 2014-2016, Germany took the stance that refugees could stay as long as they integrated into their societal model, installing education programs to see these people assimilated into the model and thus solve its demographic problem.

Lessons for Other Nations

This German story is relevant to other nations such as Australia, China and Russia, whom face similar challenges of aging demographics, reduced consumption and further dependence on exports.

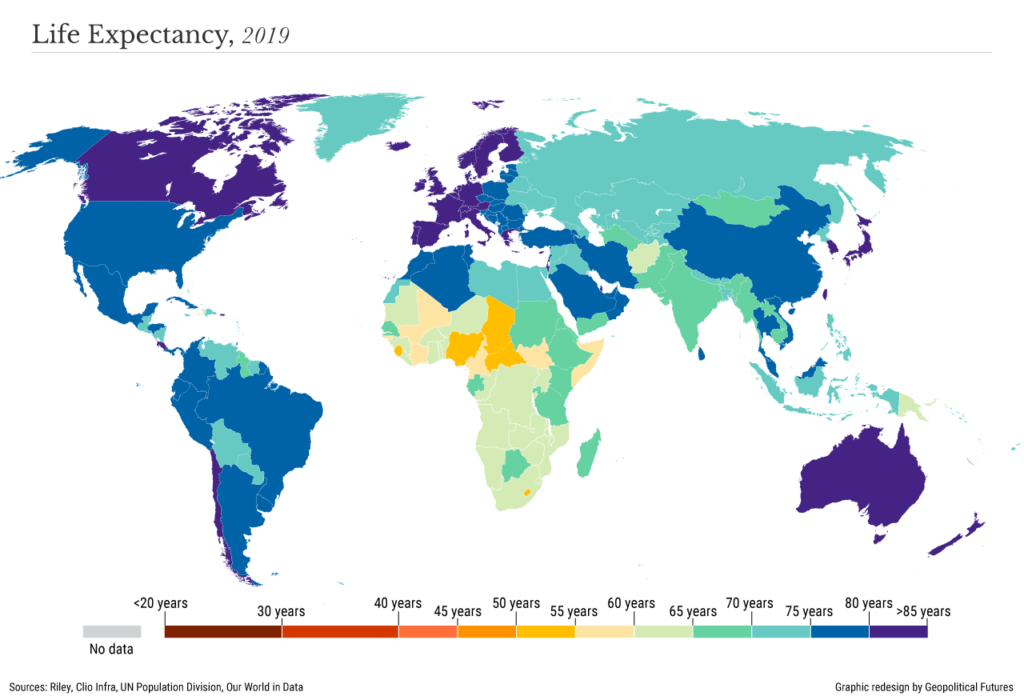

More broadly, life expectancy and birth rates have dropped, increasing the demographic dilemma.

In the USA, life expectancy dropped more than a year in 2020, while in France it fell by 6 months.

Some of this was caused by COVID19 but also by other factors like increased uncertainty, stress and anxiety. It’s unclear how long these factors will persist and how the psychological scarring will affect survivors for the rest of their lives, but it’s safe to say it will, to an unknown extent.

Post COVID-19 Outcomes

For a variety of reasons, domestic protectionist policies have slowly returned in a number of countries, posing another obstacle to export-led growth.

The healthcare crisis has highlighted the imbalance between demand (diminished) and supply (virtually unchanged), which manifested in the US-China trade conflict.

Another manifestation is the social inequality within nations, such as the dispersion of education and income across China’s urban versus regional cities and towns.

This was also seen cross-sectionally across services sectors in USA, Australia, New Zealand, UK etc. where tertiary services had more ability to work-from-home and continue regular business, relative to more “blue collar” workers who were restricted by government and self-imposed mobility restrictions.

In the UK, this extended the established trend epitomized by Brexit, where the British voting public was bifurcated by their urban versus rural realities.

Take-aways for Public Policy

Restructuring of socio-economic models is a slow process, but something governments can do quickly through adjusting educational models to support expertise and workers to new industry imperatives.

For example, Australia has been enacting micro-economic reform over the last ~15-20 years to push more students towards STEM studies, but also nursing and medicine. This push came through the use of subsidies, grants and scholarships where students had cheaper tuition requirements for studying degrees in these fields.

This hasn’t been rolled back per se, but there has been an increased emphasis on trades recently, where the Commonwealth government flagged 2.5bln AUD in last year’s fiscal budget to subsidise “tradie” related jobs.

To further this point, Gallup released a report in February on the learning experiences of high school students in the US New England area. One of the findings was that technological barriers such as internet connectivity and hardware related requirements prevented lower-income students from studying, whereas higher income students had less issues with these requirements – where stable internet and fast computers are more the norm.

Studies in Europe found similar results, where in France and Germany, technological access was dependent on household income.

According to the European Commission, more than 20% of children in Europe lack resources to effectively study at home, such as have their own room, opportunities to read, internet access and parental support for children under 10.

A lot of these issues existed pre-pandemic and will exist after it.

Learning experiences depend on the teacher and school/universities’ engagement and pedagogical method, where traditional teaching methods are being critisised both in the USA, Europe and Australia, before the pandemic.

This in particular is nothing new, as Finland – ranked #1 in the world for education – reformed their education process in the 1970s and 80s, to ensure students have a more common and universal education experience, with highly qualified (and higher paid) teachers, and support for struggling students to address inequality.

I believe former Australian Prime Minister Whitlam said it succinctly in 1974 when speaking of the precepts for what is now the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS):

“We want to reduce hardships imposed by one of the great factor for inequality in our society, inequality of luck.”

Gough Whitlam

Closing Remarks

Changes in society often outpace the changes in government policy, teaching practices and the generational disconnect between young (students) and older (teacher) generations.

Through the lens of the pandemic, the tension is more evident and greater than ever, with a need for expedited reform and change.

We don’t know how our national government – as well as foreign countries such as Germany, USA and China – will shift their socio-economic models. But as always, we need remain nimble to remain relevant.

These demographic changes are happening quickly and mean an increase to inequality, something that might raise the potential for social unrest and financial market volatility in both domestic and international assets.