When we wrote about the Communist Party of China’s (CCP) 14th Five Year Plan in March this year we identified eight key areas worthy of note, and areas to which were likely to be more impacted from an investment standpoint.

These impacted investment areas were Chinese technology, healthcare, and education – where we warned of exposure to political risk as China commemorates the 100th anniversary of the CCP and a re-linking process of Chinese corporates to CCP ideology.

Fast forward to the last three months and we’ve seen Chinese tech companies and Chinese healthcare companies come under fire, as the CCP has undergone a realignment process in keeping with their Made in China 2025 strategy.

Historically, Chinese policy has consistently undergone these stop-start transition periods, often during times of decreased economic growth, income equality or political instability.

This time the government regulatory impulse has been driven by the goal of “common prosperity”, seeking to address wealth inequity within the nation and sooth domestic angst in regard to the inequal prosperity of Chinese nationals.

Facing Reality

The reality is that until the 20th century, more than one third of China’s current landmass was not under control of the Chinese government.

In detail, these are the regions known as Tibet (India), Xinjiang (Turkey, Inner Mongolia (Russia) and Manchuria (Russia or Japan depending on the decade).

In geopolitical parlance these are known as “buffer zones”, used to create a relative defence against land invasion from other nations, where buffer zones aren’t usually homogenous populations to the “core” regions, but they are maintained as a military imperative.

Source: Geopolitical Futures

History buffs amongst us will remember the Soviet Union used a buffer zone of their own known as the Iron Curtain, where signatories to the Warsaw Pact such as Bulgaria, Albania, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Poland, Romania and East Germany formed a collective defence coalition which the USSR used for their own defence.

Han China, the China we think of as core China, maintains these regions for their own defence as buffer zones, but also to extend their own land mass and potential economic output.

Chinese Geopolitics

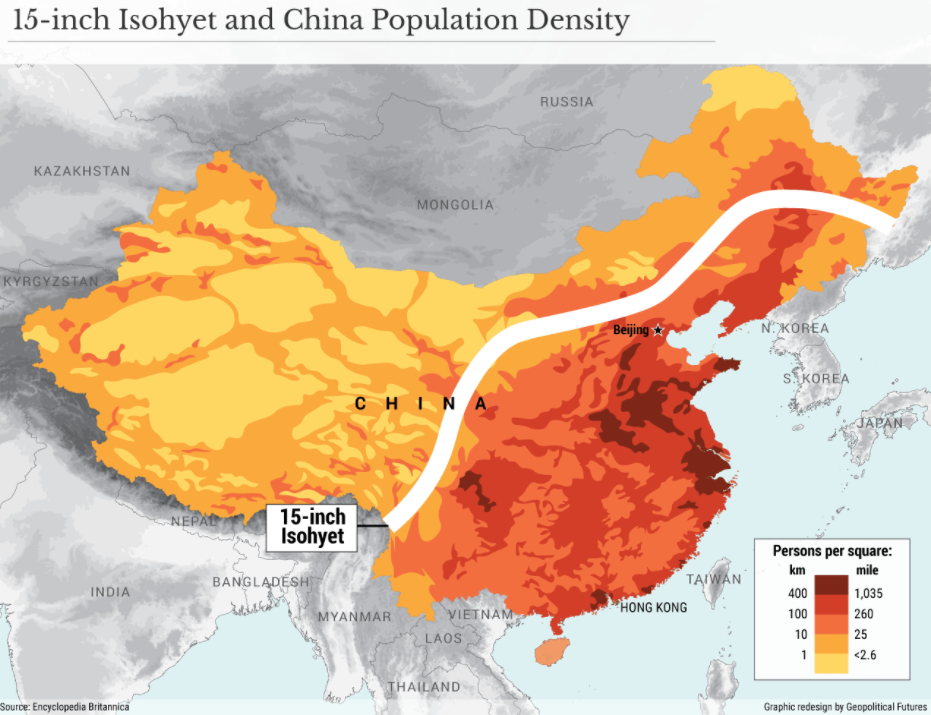

According to Geopolitical Futures, rainfall is perhaps the most important geopolitical factor for China, where to maintain agricultural production, they require a minimum of 15 inches of annual rainfall.

This creates an arbitrary line of demarcation on a map, called the “15-inch isohyet”, which roughly cuts China in half.

Source: Geopolitical Futures, Encyclopedia Britannica

On the eastern side of the Isohyet (right side) lives 94% of the Chinese population, around 1.3 billion people, creating an obvious divide where these eastern provinces must produce all of China’s domestically grown food.

On the western side of the Isohyet (left side) lives the remaining 6% of the population, mostly Tibetans, Uyghurs, Inner Mongolians – who are typically the first to experience famine when Chinese crop yields are lower, and do not have the same access to export markets the coastal provinces enjoy.

Hence, the ethnically and religiously diverse non-Han buffer regions of China tend to be the poorer regions as well, creating a military and political vulnerability within China, and an obvious reason for the recent “common prosperity” push.

In the 100th year of the CCP, they’re keenly aware and reminded of Mao’s “Long March” to Yenan, raising a peasant army and over 20 years, overthrowing the government and installing communism across the nation.

[Sidebar: I realise this is a historical and philosophical simplification, but we do the best within our word count limits]

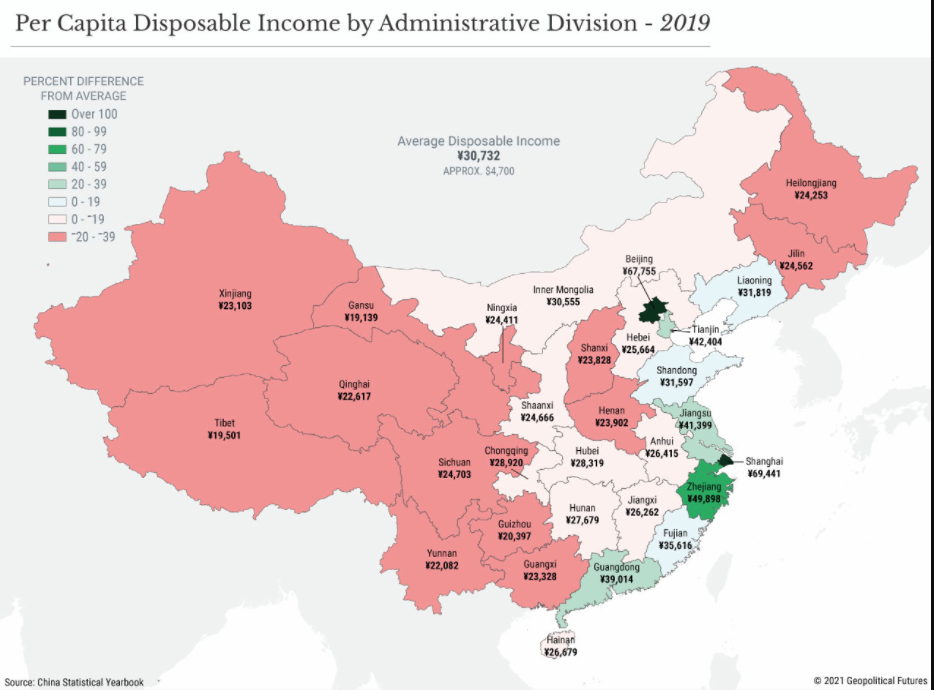

Source: Geopolitical Futures, China Statistical Yearbook

Whilst the Long March was some 86 years ago and China’s economy has become the world second largest behind the USA in this period, it only ranks 75th in the world on a per capita basis, where coastal regions such as Fujian, Guandong, Shandong or Beijing have 2-3x higher per capita GDP than inland provinces like Xinjiang, Tibet, Gansu or Qinghai.

Knowing this, it’s no wonder that the One Belt, One Road initiative was contemplated, developing an internal infrastructure to expand the trading horizons for the buffer zone regions, to create a more “common prosperity” across all of China, not just core (Han) China.

Chinese Geopolitical Imperatives

China’s geopolitical imperatives are therefore as follows:

- Generate sufficient wealth to prevent fragmentation and unrest between regions

- Because it cannot generate sufficient wealth internally for these buffer zones, it must provide greater access to export goods and services

- China must have access to global markets via both land and sea, where denial of that access is an existential threat

- The low wages and manufacturing costs of some of these poorer regions will be seen as anti-competitive by global competitors, which can invite varying forms of retaliation

- Buffer zone areas must be controlled to curtail internal and external unrest, where there’s global outrage regarding the treatment of the Uyghurs in Xinjiang, and how their population is being controlled

Implementation of Imperatives

Recently, Chinese regulations have been driven by the common prosperity goal, targeting income inequality but also labour, health, and education.

This has been deeply imbedded into the newly adopted social credit system, which allows for increased social mobility and alignment to CCP ideology, but also command and control politics.

The dream is to provide poorer people the opportunity to climb the social hierarchy – as long as they’re good CCP supporters – giving enhanced access to finance, education and wealth opportunities.

As well, the implementation of the recent realignment agenda has been somewhat vague, encouraging companies rather than strictly enforcing cooperation.

For example, it was pointed out in recent RWC Emerging Markets Fund (APIR CHN8850AU) commentary that Tencent (HK: 0700) has made investment in social responsibility programs, as a gesture to embrace government policy.

The nuance is that Tencent weren’t transparent in the time frame for the 50 billion RMB (~10.52b AUD equivalent) program, nor whether the investment would be for social enhancement or external donation, where RWC expect similar proactive announcements from other Chinese companies in coming months.

Another trend we expect at Mason Stevens would be for Chinese companies to increasingly IPO within the Chinese equity markets, rather than seeking offshore listing.

This helps create a common prosperity of Chinese investors, and the impetus for foreign investors to access Chinese onshore markets via Chinese brokerages and banks, to gain access to these lucrative listings.

As a by-product, this will slowly establish the utility of the Chinese currency and promote its reserve status and use in portfolio construction, and as an alternative to the USD for both international trade and investment, also enhancing the potential prosperity and international purchasing power of Chinese citizens.

In fact, technology and finance are two of the most important industries for the CCP’s common prosperity goals, as they transcend geography and can be used to bring increased wealth to regions west of the Isohyet.

Outlook

As mentioned in the opening preamble, China has historically shown a stop-start pattern to regulation, where change tends to come in a flood, usually as a result to internal turmoil or slowing economic growth.

As such, China is more a defensive power rather than an offensive one, where its fundamental strategic interest is to preserve the unity of core (Han) China and maintain order in its buffer zone regions.

In keeping with the Made in China 2025 policy, China will maintain their trajectory to be the largest global exporter of goods and services where inasmuch as the USA is the world’s largest importer, there will be continuing tension regarding price competition, living standard of employees within supply chains and access to trade routes.

While we slightly down weighted Chinese exposure in our own ETF models in recent months, underweighting the sectors facing the near-term headwinds (property, healthcare, education), we remain positive on the outlook where we’ll continually reassess when the regulatory impulse recedes, and we can add to long positioning.

The views expressed in this article are the views of the stated author as at the date published and are subject to change based on markets and other conditions. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Mason Stevens is only providing general advice in providing this information. You should consider this information, along with all your other investments and strategies when assessing the appropriateness of the information to your individual circumstances. Mason Stevens and its associates and their respective directors and other staff each declare that they may hold interests in securities and/or earn fees or other benefits from transactions arising as a result of information contained in this article.