The imposition of COVID-19 on societies across the globe may have lead investors to doubt the future prospects of commercial property, while the opposite has occurred in many nation’s residential property markets, as the rise of working-from-home arrangements has re-emphasised more than ever the importance of private dwelling ownership.

This is also supported by the lowest interest rates (borrowing rates) in history, for most of the globe.

The increased attractiveness of residential property is most noticeable in New Zealand, which has had a frothing residential property market for some years, despite macro-prudential tools (leverage ratios and foreign buyer restrictions) employed to reduce demand for NZ domiciles.

This year, certain parts of NZ have seen large increases in property prices, despite the nation experiencing the sharpest economic contraction since the Great Depression.

This saw NZ Finance Minister Grant Robertson draft a controversial public letter, requesting the Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ) to change their operational objectives to include house prices – breaching the traditional line of demarcation between government and central bank independence.

By drawing a direct comparison between the RBNZ’s asset purchase program (“quantitative easing”) and housing price inflation, MP Robertson was getting ahead of one of the most promising asset classes of 2021 – residential property.

Specifically, urbanised areas and inner-city domiciles.

I interpreted this as Robertson trying to get ahead of potential NZ house price appreciation, to address affordability before it becomes a future election issue.

However, this was an elected government official seeking the “independent” central bank to change their policies.

Central bank independence

I’ve written about the importance of central bank independence, most recently in August (has it been four months already?), where I cited several economist’s views as to why central banks have been set up as independent from federal governments.

To reiterate our former RBA Governor, Bernie Fraser, in 1994:

“…the tendency for policy makers and politicians to push the economy to run faster and further than its capacity limits allow, and the temptation that governments have to incur budget deficits and fund these by borrowings from the central bank.”

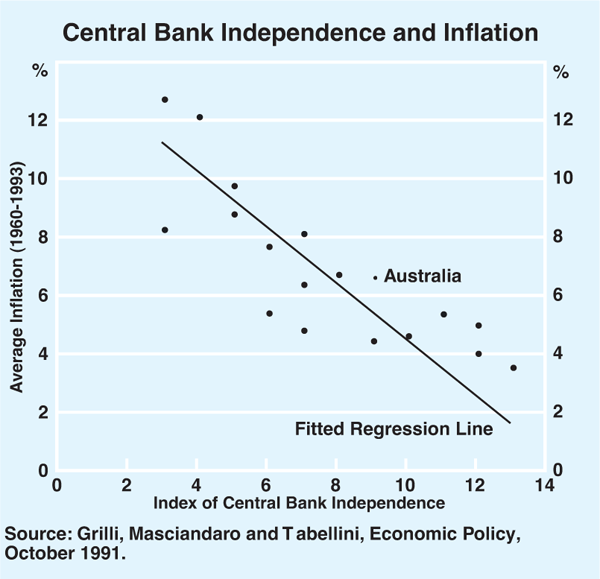

Mr. Fraser also cited the relevant academic literature at the time, that showed central banks that were independent from government influence were better at achieving inflation policy objectives.

Autonomous, not independent

The emerging trend is that central banks are no longer independent, though have different degrees of autonomy.

We can see this in the influence of Robertson in censuring the RBNZ, in US Treasury Secretary Mnuchin forcing the US Federal Reserve to return unspent reserves allocated during March 2020, and even in the annual reaffirmation of the RBA’s inflation target by our Commonwealth Treasury and RBA governor.

This serves as a reminder that for all central bank claims of independence, central banks are better viewed as autonomous.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) draws the distinction as follows:

“Autonomy is sometimes preferred to the frequently used term independence, as autonomy entails operational freedom, while independence indicates a lack of institutional constraints.”

Central bank increasing involvement in economies

This is all increasingly important because central banks are playing an increasingly larger part in the global economy.

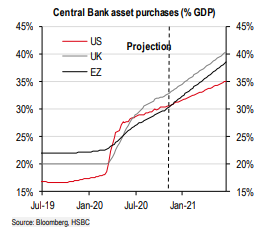

Take for example 3 of the 5 largest central banks in the world, US, UK and European Union – all three have purchased government debt equivalent to over 30% of annual economic output (GDP).

Couple this with government expenditure accounting for 40% or more of total annual economic output in most major economies, the combined total of economic support and influence from governments and their agencies (including central banks) is immense.

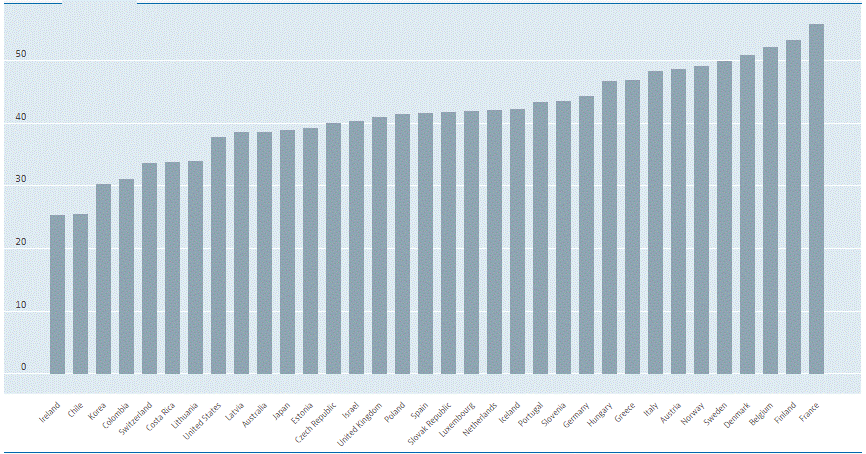

The below graph shows government fiscal expenditure as a percentage of economic output, as at 30 June 2020:

Source: OECD

Because of this increased reliance on government and central bank support, the global economy is heavily indebted, where central banks are unable to materially increase interest rates in the future, lest they cause large increases in economic output as financing costs increase.

As per the above chart, government expenditure is 40-50% of national economies, and they require their central bank agencies to support them – eroding the independence, though trying to remain autonomous.

Property markets

Circling back to residential property markets, the RBNZ should be aware that its response to Finance Minister Robertson’s missive is going to be closely scrutinised around the world.

In Australia, RBA Governor Lowe spoke in the House of Representatives on 2 December and stated (emphasis mine):

“The [RBA] recognises that its decisions have an uneven effect across the community.”

“At previous hearings we have discussed the effect of low interest rates on housing prices, the incentive to borrow, and medium-term economic and financial stability. These remain issues that we are continuing to monitor.

But in the current environment, the bigger stability risk is a protracted period of high unemployment, rather than excess borrowing.”

I interpret this as a free kick for residential property investors in 2021 and 2022, where property markets’ structure will be supported by monetary policy accommodation that won’t be reduced for several years – until unemployment drops back to pre-COVID levels – by increased demand through working-from-home arrangements, by the changes to stamp duty reform from the NSW government, and by the on-going government subsidy for property investment (negative gearing).

Let us not forget the Commonwealth government’s efforts to overhaul the National Consumer Credit Act (i.e. the responsible lending laws), which will be important if not materially altered as the legislation passes through the Senate.

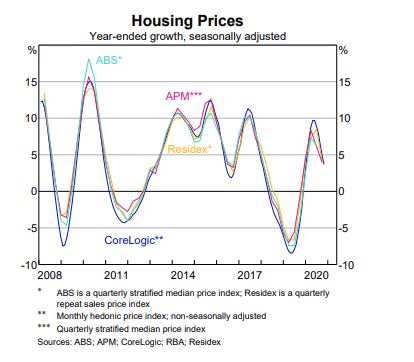

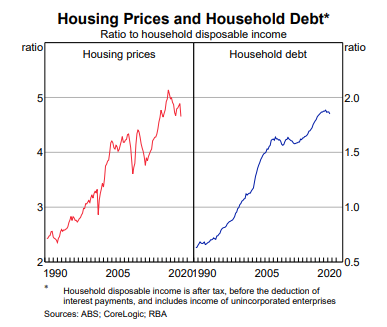

This may again allow banking institutions to lend more freely, allowing more buyers/entrants to the property market and overall aggregate demand – and possibly extend the below chart’s lines higher and higher.

Closing remarks

Conducting my due diligence and then writing this note made me far more bullish on Australian residential property than when I began.

The evidence is mounting up that easy monetary policy through cheap loans and broader availability of credit provide the structural demand for Australian residential property – along with increased importance from work-at-home arrangements providing more marginal buyers of residential property as opposed to commercial property or commercial leases.

Hence, while our national property market’s value has fallen slightly in 2020, we may see it return to 5-10% annualised growth – which is only our average growth rate over the last 20 years.