The Reserve Bank (RBA) met yesterday and while the market predicted most of the resulting change in monetary policy setting, the Bank did provide some unexpected surprises.

The point of policy

In our missive on 26 October, we sought to explain that monetary policy has become less clear because of the multiple policy initiatives being employed to affect economic responses.

In summary, the RBA is enacting policy changes in order to fulfil their mandated goals, and to provide the liquidity and transparency to markets during a period of heightened uncertainty and volatility.

Why make changes?

We must remind ourselves that the RBA always has their three federally mandated objectives in their crosshairs:

- Currency stability

- Full employment

- Welfare and prosperity of Australians

The RBA and Commonwealth government agree that the best way to achieve these objectives is through inflation targeting, and are manipulating their monetary policy mechanisms in an attempt to achieve their mandate.

Inflation has consistently averaged below the target of 2-3% p.a., and the RBA is taking steps to see inflation rise.

Furthermore, the market’s forecast for 10-year inflation is 1.4-1.6%, which shows that average inflation expectations are below the RBA’s target band as well.

Policy initiatives

- Reducing the Overnight Cash Rate (OCR) target from 0.25% to 0.1%

- Maintaining the OCR at the current low level for at least three years

- Reducing the Term Funding Facility (TFF) rate from 0.25% to 0.1%

- Reducing the 3-year government bond target yield from 0.25% to 0.1%

- Reducing the Exchange Settlement Account (ESA) rate from 0.1% to 0.0%

- Expanding their asset purchase program (quantitative easing) to 100bln AUD of Commonwealth and State/Territory issued bonds, of 5-10 year maturities, over the next 6 months

My summary of these changes

#1 Reducing the OCR and maintain it for 3 years

The reduction of the OCR to 0.1% was expected by the market and will have little overall impact on the economy. The Overnight Cash Rate is an inter-bank lending rate that has played less and less a role in the aggregate funding composition of domestic banks, so the reduction will have small impact compared to other policy tools.

The act of “forward guidance” for the cash rate is in keeping with the other policy measure of managing 3-year government bond yields to 0.10% (#4), as this effectively rules out all uncertainty of the cash rate from an overnight maturity, to a November 2023 maturity.

If everyone knows the policy will be in place for 3 years (or more), it provides the stability and confidence the market is seeking during this uncertain time.

#2 Reducing the rate on the Term Funding Facility (TFF)

The TFF is a relatively unknown policy initiative as it was established in March 2020 by the RBA to assist banking institutions with their ability to fund themselves at low rates – during a period where wholesale funding was harder to obtain.

The TFF has a current capacity of $197.1bln AUD and has seen 82.9bln AUD of drawdowns since March, a 42% utilisation rate.

In other words, this is a potential $83bln AUD that Australian based banking institutions have utilised this year where they haven’t needed to draw upon capital markets – something they would’ve been eager to do given the much lower cost of funds in the RBA facility compared to the market.

This policy response limits forthcoming supply of senior unsecured bank debt and has buttressed the rally in Australian domestic credit bonds this year.

#3 Reducing the Exchange Settlement Account (ESA) rate

ESAs are bank treasuries clearing accounts with the RBA.

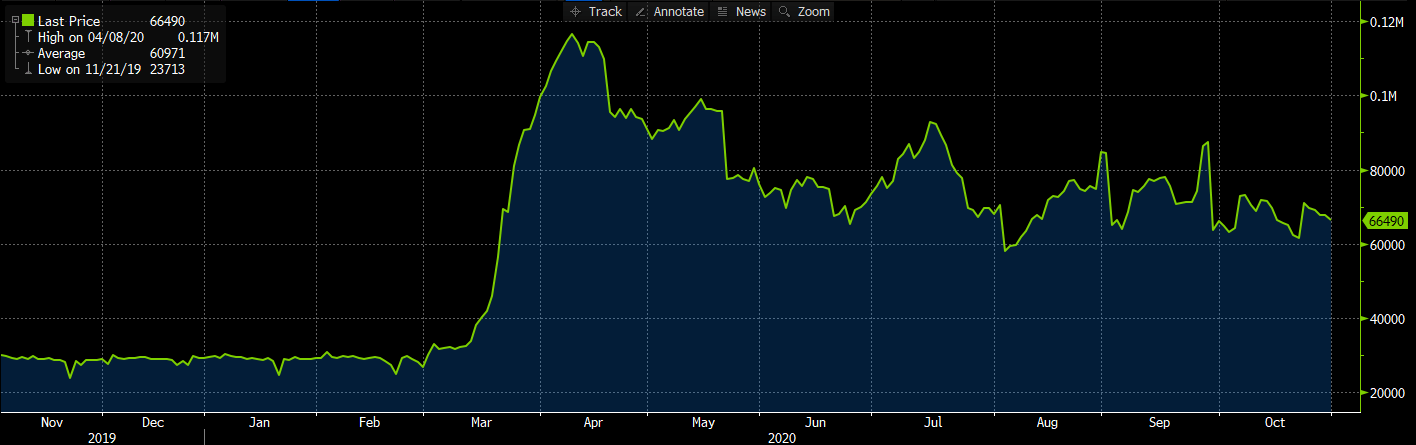

Traditionally, the balances have been kept minimal to a float that covers daily payment volumes. However, this year, the deposits have soared from $25 to $120 billion and then back to $66bln at present, as the RBA was seen as a safe haven for cash for those existing “risk” asset markets.

By reducing the ESA rate from 0.1% to 0%, the RBA is incentivising banks to deploy their cash into non-cash assets (money markets and fixed income mainly), to seek a higher return.

If not, the banks will see a resulting drop in earnings.

Source: RBA

#4 Expanded Quantitative Easing (QE)

The RBA has stated they will be purchasing up to $100bln AUD of Commonwealth and State/Territory (“semi”) issued bonds over the next 6 months, with a yield target of 3-year Commonwealth and semis at 0.1%.

This will split 80% govies, 20% semis.

This was partially expected by the market with government bonds trading on the secondary market at yields of 0.11 to 0.12% prior to the RBA announcement.

However, the size of the QE programme increase was definitely a more aggressive move, as fund managers were expecting a “flexible” target based on market conditions, rather than a specific number.

Implications for the yield curve

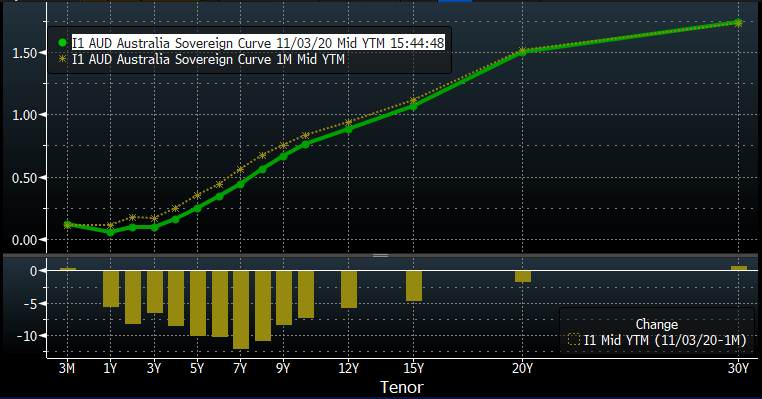

Immediately after the RBA published its policy update, the market reacted to the news and re-aligned with the current monetary policy setting.

The short end of the yield curve (overnight to 3 years) re-priced yields from 0.04% at the shortest part to 0.10% 3 years.

The longer end (10 years to 30 years) has barely moved.

In the below chart, I graph this by comparing the government yield curve today (green line) versus the yield curve one-month ago (yellow line).

Source: Bloomberg

This result is what’s known as a “bull steepener”, i.e. bonds have rallied (bullish) and the overall yield curve from start (overnight) to finish (30 years) is steeper.

Generally, steeper yield curves are supportive for bank earnings, as they tend to borrow short-dated funds (overnight deposits) and lend for longer periods (30-year mortgages) which is known as an asset-liability mismatch.

This isn’t exactly the case, but should highlight why Policy #3, a reduction in yields on Exchange Settlement Accounts (ESAs), will be partially offset by the steeper yield curve and mute the overall impact to bank earnings.

Implications for credit markets

Broadly speaking, the RBA’s change of monetary policy accommodation is positive for credit spreads and credit bonds.

New bank issued senior unsecured debt will be less forthcoming as the TFF can be further utilised to fund upcoming maturities, or to fund balance sheet expansions.

Also, the reduction in risk-free rates will flow into a reduction in overall market yields, all else remaining equal, which reduces funding costs of corporate issued debt.

Final remarks

The RBA has continually underachieved their targeted outcome of average CPI of 2-3% per annum over the last decade.

Furthermore, COVID-19 has exacerbated this underperformance by creating a demand gap, where aggregate demand is far lower than aggregate supply.

The result is lower inflation (disinflation) and an unsatisfactory outcome for the RBA.

Hence, they are doing their best to stoke the “animal spirits” of the economy, and see demand return through disincentivising various forms of savings (household and corporate), so that investment and consumption pickup over the short to medium term.

Last week, former head of the New York Federal Reserve Bank Bill Dudley was quoted saying:

“No central bank wants to admit that it’s out of firepower. Unfortunately, the U.S. Federal Reserve is very near that point. This means America’s future prosperity depends more than ever on the government’s spending plans – something the president and Congress must recognise.”

What Mr. Dudley was saying is that while the central banks around the world ease policy, the heavy lifting needs to come from government and corporate balance sheets – something the RBA has been saying for the last 1 to 2 years already.

Therefore, I find it hard to see the RBA being successful in achieving their goal of higher and sustained inflation in Australia, and understand they have to be visible in the market in trying to be seen doing something.

However, until the private sector rebounds post-COVID and drives economic growth, inflation is likely to remain lower for longer, just like monetary policy and interest rates.

The views expressed in this article are the views of the stated author as at the date published and are subject to change based on markets and other conditions. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Mason Stevens is only providing general advice in providing this information. You should consider this information, along with all your other investments and strategies when assessing the appropriateness of the information to your individual circumstances. Mason Stevens and its associates and their respective directors and other staff each declare that they may hold interests in securities and/or earn fees or other benefits from transactions arising as a result of information contained in this article.