On 1 July 2020, Indonesia’s central bank closed an agreement with the government to fund $40bln USD at zero% interest rate, to fight the coronavirus pandemic.

This is the largest debt monetisation program among emerging market nations so far.

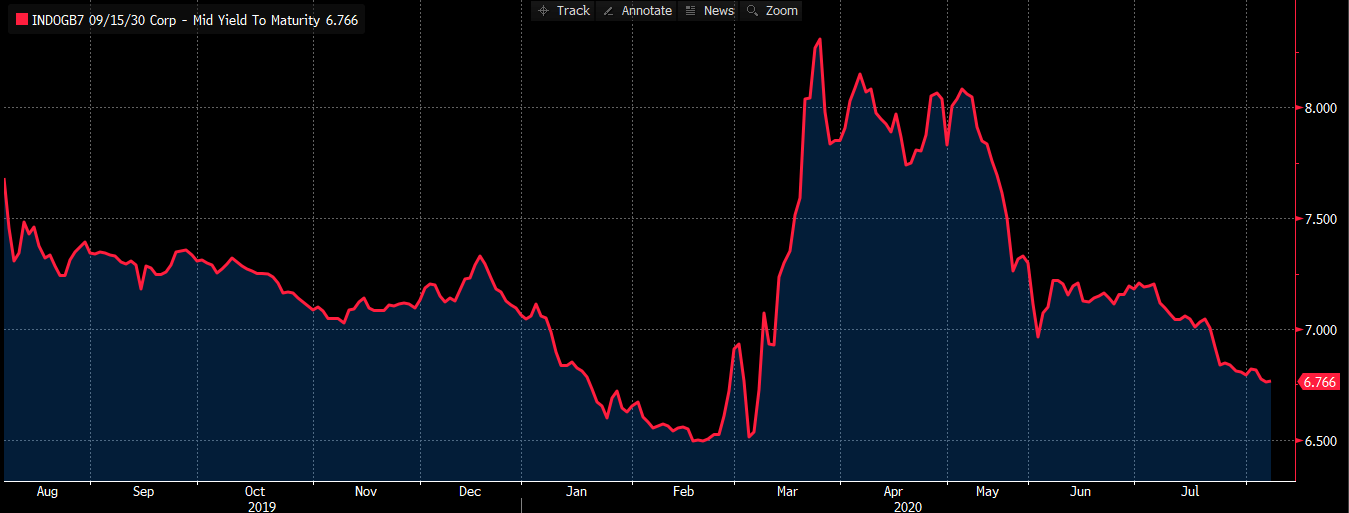

While Bank Indonesia (BI) had been already buying government bonds at primary bond auctions and in secondary markets to help constrain bond yields to assist the government in financing its budget spending, this latest agreement is one-step further into the realms of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT).

The reason that this agreement is distinct from what other nations are doing is that the agreed rate was not a market interest rate (zero% versus Indonesian bond yields of 6-7%), and the intent was clearly outlined.

Directly monetising budget deficits has long been a taboo topic, especially for emerging markets, and raises the potential risks around inflation and the central bank’s independence.

Potential risks of inflation – such as has been experienced in Turkey, Venezuela and Argentina through their previous MMT experiments – and central bank independence which is vital in ensuring a stable and independent monetary policy that doesn’t support egregious economic behaviours.

If you’re after a primer for MMT – we’ve written one available here.

Why is Bank Indonesia doing this?

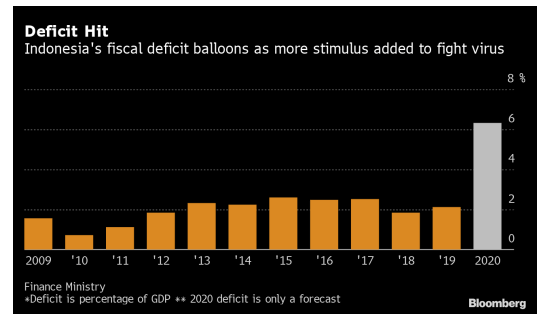

The Indonesian government was facing the daunting task of borrowing 1.65 quadrillion rupiah (112.4bln USD) in 2020 to fund a budget deficit 6.34% of their 2019 GDP.

The COVID-19 pandemic has decimated their fiscal budget, with government revenue plummeting whilst borrowing has increased.

As a response, President Widodo scrapped a fiscal deficit cap of 3% of GDP – set back in the Asian Financial Crisis (1997-1999) – in order to allow the government to spend more to finance public welfare spending.

Source: Bloomberg

Concurrently, a severe sell-off in emerging market bonds and currencies in Q1 2020 meant the Indonesian Treasury had little to no access to global capital markets to raise external financing and turned to the central bank for support.

Though I note, this effective shut-out from bond markets was primarily March and April, and this MMT/financing deal has come about in July.

Risks of Debt Monetisation

Deficit financing, especially the printing of money to fund government spending, is associated with inflation and undermines independence of a central bank.

While inflation remains low and under control in Indonesia for now, the country has been prone to spikes in prices in the past.

Also, the country faces risk of a credit-rating downgrade if their debt metrics deteriorate further. This lower rating can reduce their ability to borrow in global capital markets further, reducing the likelihood that MMT is curtailed.

One Month Later

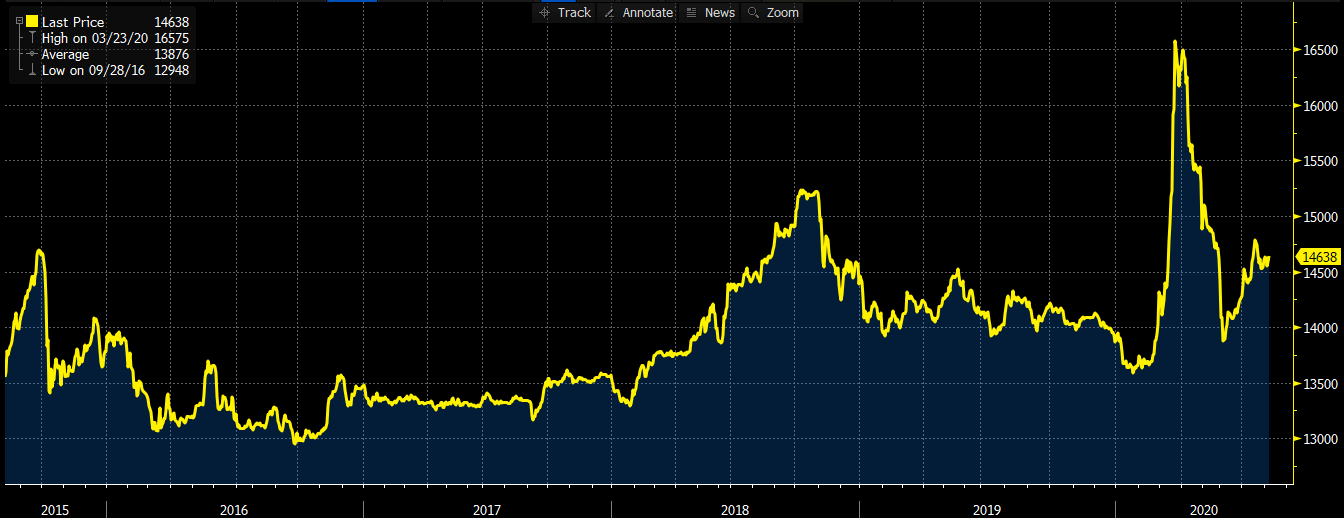

The two key barometers for Indonesia financial markets are their 10-year government bonds and the other is the USD versus Indonesia Rupiah (IDR) exchange rate – quoted as USD/IDR.

Post announcement, the 10-year government benchmark bond has rallied from 7.2% yield to 6.85% and while the price is not yet back to the all-time-high seen in Feb, it’s nearly there.

Source: Bloomberg

As for the Indonesian exchange rate, a single USD buys approximately 14.6k IDR, while this isn’t the all-time low for Indonesian rupiah which was experienced in March 2020, it’s very close to it.

Source: Bloomberg

So Far So Good?

Indonesia differs quite starkly to our domestic monetary policy.

On 21 July RBA Governor Philip Lowe was quite specific in why MMT would not be suitable in Australia.

Governor Lowe set out the three conditions that would need to be present for Australia to consider MMT:

- conventional monetary policy options have been exhausted

- the central bank is falling short of its goals

- public debt is high, and the government cannot borrow in financial markets on reasonable terms

In Indonesia’s case:

- is far from exhausted with quite a high cash rate by world standards,

- inflation has averaged 3% over the medium term, and Bank Indonesia’s target for inflation is 3% +/- 1% – so they’re achieving target

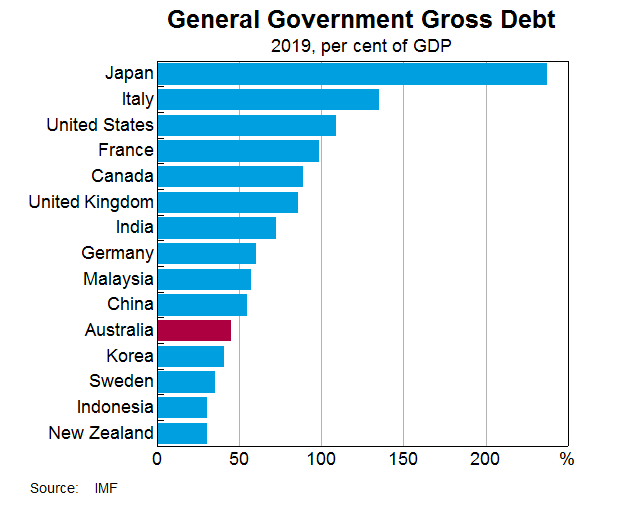

- Indonesia has quite low government debt levels are they are not shut-out from global markets.

Post-mortem

Indonesia was able to successfully conduct a form of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) because they’re in relatively fine budget health, and the increase in gross government debt would’ve been manageable without MMT.

This begs the question why the government has gone through with MMT, which in my view, comes across as politically motivated to manage cost of debt servicing, though comes at the cost of the central bank no longer remaining independent.

In terms of people politically motivated; the originally agreed rate of interest was zero% for the 40bln USD of loans, completely untethered from the market interest rate of Indonesia’s government debt yielding 6-7%.

Central Bank Independence

The hallmarks of independence – namely, autonomy from government and non-financing of budgets – were identified by classical economist David Ricardo in a paper on the establishment of a national bank in 1824 (page 420).

“It is said the Government could not be safely entrusted with the power of issuing paper money; that it would most certainly abuse it…”

“If Government wanted money, it should be obliged to raise it in the legitimate way; by taxing the people; by the issue and sale of exchequer bills; by funded loans; or by borrowing from any of the numerous banks which might exist in the country; but in no case should it be allowed to borrow from those who have the power of creating money.”

Furthermore, I’ll refer to our RBA, as ex-RBA Governor Bernie Fraser once stated in 1994 in favour of central bank independence:

“…the tendency for policy makers and politicians to push the economy to run faster and further than its capacity limits allow, and the temptation that governments have to incur budget deficits and fund these by borrowings from the central bank.”

At the time, empirical evidence also substantiated that central bank independence leads to better fulfilment of price stability (inflation) policy mandates.

Future of MMT

I believe we’ll keep hearing more and more about MMT and possible uses across the globe.

That the RBA Governor sought to address questions of MMT in his July address at the Anika Foundation lunch was evidence that there have been internal and external questions to the RBA regarding the topic.

The fact that the Bank of Indonesia gave in to political pressure to fund the government is also evidence that central banks are being sought to address record COVID-19 debt issuance and subsequent debt servicing costs and repayments.

The views expressed in this article are the views of the stated author as at the date published and are subject to change based on markets and other conditions. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Mason Stevens is only providing general advice in providing this information. You should consider this information, along with all your other investments and strategies when assessing the appropriateness of the information to your individual circumstances. Mason Stevens and its associates and their respective directors and other staff each declare that they may hold interests in securities and/or earn fees or other benefits from transactions arising as a result of information contained in this article.