Over the weekend, numerous Western nations combined efforts to step-up the economic retaliation against Russia for invading Ukraine, a dynamic environment where more is happening and more detail forthcoming each day since.

The sanctions began on 24/Feb, when the USA, UK, Canada and EU imposed restrictions against President Putin, Foreign Minister Lavrov, Defence Minister Shoigu, military chief Gerasimov, as well as hundreds of members of the Russian parliament and Security Council, as well as various businessmen and oligarchs, freezing assets and banning them from international travel.

The most important measure was announced over the weekend, a decision to cut-off select Russian institutions from the global electronic payment-messaging system known as SWIFT.

This move has barely ever been used before, though not without some precedent, used against Iran in 2012 as they pursued nuclear ambitions and were blacklisted by the European Union and faced sanctions from the USA.

The precedent isn’t too applicable, though, as Iran was fairly insulated from the global financial system and a relatively small economy, whereas Russia is far larger and far more connected to global financial markets and trade.

The news to cut-off Russia produced a swift market reaction (sorry, pun had to be used) over the weekend and Monday morning, and was touted as the “nuclear” option ahead of time.

But this all begs the questions, what is SWIFT and what are the implications for financial market fallout and any contagion?

What is SWIFT?

SWIFT stands for Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication.

If the acronymic title didn’t give it away, it’s an old school messaging system founded in 1973, created to replace the telex network (fax-like teleprinters), and is used to reconcile payments between global banks and other corporates.

According to SWIFT, over 10,000 banking institutions and over 200 countries use SWIFT messaging as the plumbing for their payments systems.

Example of a SWIFT Message

Global payments systems are still relatively unsophisticated, where the SWIFT system really hasn’t improved in the past 40+ years.

As an example, if you want to send money back to your family in Ireland in EUR, to their local bank account, your payment will be using the SWIFT system.

Your bank will convert your AUD into EUR by selling the AUD/EUR cross-rate, for the appropriate amount you wish to transfer.

Then your bank will transfer the EUR they now hold on your behalf to the foreign bank’s EUR clearing account, likely with the European Central Bank.

If your relative’s bank doesn’t have an account with the ECB, then likely the money transfers to a 3rd party (agent) bank, who then sends the money on to your relative’s bank.

In order to reconcile the transfers from your account at XYZ Australian Bank, to foreign EUR bank, to your relative’s account, SWIFT messaging is used.

For reference, the above hypothetical is called a MT103, or a “single customer credit transfer”, with tens of thousands of MT103 processed daily across the globe, let alone the other hundreds of different message types (MT).

Why SWIFT Matters

SWIFT is making the news because it can be used as a powerful financial weapon against any nation or actors that break global codes of conduct.

SWIFT is owned by over 2000 banking institutions, overseen by the National Bank of Belgium, in partnership with major central banks such as the US Federal Reserve and the Bank of England.

By removing SWIFT access for Iran, or more recently, from Russian banks is an impediment to access global money flows, making it harder for Russian banks and corporates to export or import, or to source non-domestic forms of finance.

In the near-term, the Russian economy now faces significant disruption, as it now needs to adjust to new payment platforms and messaging reconciliation.

More Difficult, Not Impossible

This development makes economic activity more difficult, not impossible.

Back in 2014, when Russia annexed Ukraine’s Crimea Peninsula, there were similar calls to cut Russia off from SWIFT then-and-there, which didn’t happen.

The Kremlin took the threat seriously, however, and subsidised the development of a domestic financial communications platform to protect itself.

The infrastructure is called System for Transfer of Financial Messages (SPFS), and has over 400 member banks, including banks from over 24 former Soviet Union states, and handled more than 20% of all Russian payments volume and messaging in CY2020.

Hence, Russia has some ability to navigate around the SWIFT restrictions, though transaction costs will increase dramatically, and processing delays are sure to occur.

Getting Around the Sanctions

While we’ve already mentioned the use of SPFS to bypass needing to rely on SWIFT, it’s also worth noting that China has already been developing their own payments messaging system called Cross-border Interbank Payment System (CIPS), in case China was ever to be cut-off from SWIFT as well.

Though news has been less forthcoming these past three years, there was talk in 2018 and 2019 as the US/China trade war and deglobalisation tensions were building, that Russia and China would create a bridge between SPFS and CIPS so that the two nations could continue to trade and disintermediate both Europe and North America.

Both nations also diversified their national reserves away from USD holdings, adding more gold, EUR, GBP, CNH, JPY exposure, so as to lessen their reliance on the USD market and their need to transact in US dollars as a universal currency.

In Russia’s case, their central bank has built-up its national reserves as well, which as of 31-Dec-2021 exceeded 620 billion USD (equivalent), or the fourth highest amount of reserves in the world, behind China, Japan, Switzerland and roughly equal with India.

Special Drawing Rights

Something I’m yet to see much press, but am waiting for the eventual inclusion, is the restriction of use of International Monetary Fund (IMF) Special Drawing Rights (SDR), as governments can use their SDR assets to convert into hard currency, without ever having to repay them.

Last year, the IMF issued 650billion USD of SDRs, with Russia allocated 17.5 billion USD.

The Russian government could effectively draw upon these SDRs for their full notional value, adding value to their already significant FX reserves, and then never seek to repay the IMF.

Obviously, this skirts the sanctions and would be a policy tool the United Nations could seek to amend so as to not finance Russia or other regimes of similar nature.

Possible Medium-Term Own-Goal

I can’t help but think the weekend’s news of a Russian SWIFT-ban might become a medium-term own-goal, where the new sanctions force Russia and possibly other nations to move away from SWIFT and diversify their use of USD and EUR, insulating them further and limiting the scope of other such sanctions.

Moreover, there’ll likely be a significant amount of R&D to develop decentralised finance (DeFi) and cryptocurrencies (both state sponsored and not) that allows greater and unfettered access to global finance and transactions.

Short-Term Pain

The medium to long term view aside, this news creates significant uncertainty as the extent of the sanctions and SWIFT ban become known.

Last Thursday, the Bank of International Settlement (BIS) reported that the largest national exposures to Russia are in Italy, France and Austria, owed 25, 17.5 and 14.7bln USD respectively.

While this made a dent in those nation’s bank equity prices on Friday, the stock price declines were not all that large, where the common assumption seems to be that loan repayments will be allowed through, rather than letting Russian government agencies, or Russian corporates default on their loan obligations and effectively hurting non-Russian entities.

Case in point for my views has been the price-action of Russian credit default swaps (CDS), a derivative-instrument used as a form of insurance, and in this case, referring to the live default probability of the Russian Federation.

The price of the USD-denominated 5-year contract has moved from 124bp p.a. on 31-Dec to 917bp on 24-Feb, back to 553bp as I write this note.

Source: Bloomberg, as at 28/Feb/2022

This price reaction resembles a knee-jerk reaction function, where the news of the invasion and the possibility of cutting Russia off from SWIFT was perceived to be the precepts of Russia not being able to repay its foreign-denominated debt, only for the news to be less impactful and less severe, and the credit default pricing came back down.

Working against this narrative are Russian government bonds, where Russian 10y treasuries are currently yielding 15.99%, up from 8.7% at the start of the year.

Source: Bloomberg, as at 28/Feb/2022

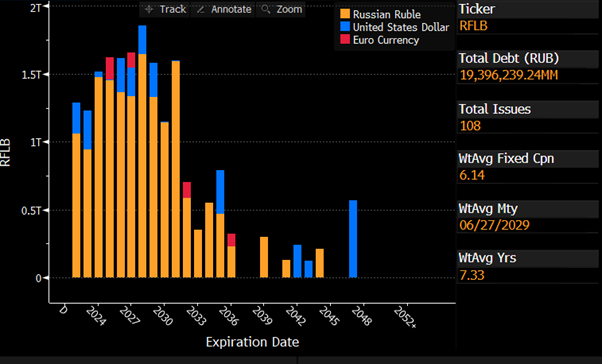

Putting this in perspective, Russia has 239.5bln USD of government debt outstanding, though the vast majority of this is denominated in Russian rubles (200bln), the rest in USD (33.9bln) and EUR (5.94bln).

If Russia were to default on their debt obligations, having already been downgraded from investment grade to “junk” (sub-investment grade), this would have ramifications for other markets, primarily European, as the largest non-Russian holders of Russian debt.

Source: Bloomberg, as at 28/Feb/2022

The inflationary impact of the RUB devaluation cannot be understated as well, where the Russian central bank has on Monday hiked their key rate (they don’t use a cash rate, they have a 1 week rate) from 9.5 to 20% p.a., in an effort to stabilise the currency and avoid hyperinflation.

Closing Remarks

As dynamic and evolving as the situation is, we’ll do our best to summarise the key points as they occur.

The views expressed in this article are the views of the stated author as at the date published and are subject to change based on markets and other conditions. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Mason Stevens is only providing general advice in providing this information. You should consider this information, along with all your other investments and strategies when assessing the appropriateness of the information to your individual circumstances. Mason Stevens and its associates and their respective directors and other staff each declare that they may hold interests in securities and/or earn fees or other benefits from transactions arising as a result of information contained in this article.