Sometimes I come across insights that shape my view of the world, and sometimes shock me profoundly and make me reconsider some of the concepts or structures that we take for granted.

One that I’ve come across in the last month and spent more and more time reading into has been the impact of criminal records on labour force participation rates.

This might sound like a small facet of life, but in fact, it is deeply impactful to our current monetary and fiscal policy setting, and view of inflation and financial markets.

A little background to start.

Worker Availability

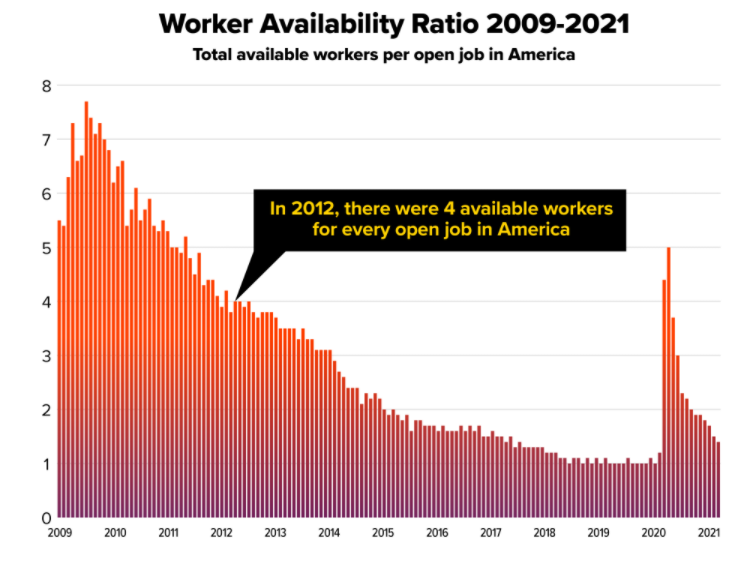

The US Chamber of Commerce (CoC) produces a different calculation of employment to the US government Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS).

The CoC divide the number of job openings by the number of unemployed yet available workers to derive a “Worker Availability Ratio”.

Source: US Chamber of Commerce

As the CoC represents US businesses, from their perspective a higher ratio is better, as it means there’ll be more applicants available to apply for any new job businesses are hiring for.

However, considering this alone would be flawed thinking as if there’s not enough jobs to go around, there’s obviously unemployment and less people to buy your businesses’ products.

What we can see is that worker availability has fallen since the 2007/2008 GFC when unemployment was at its peak of the last 15 years.

This trend continued until 2018/2019 (pre-COVID) when US consumer confidence and business expectations surveys such as NFIB highlighted that the US economy was at risk of overheating, because businesses were desperate for qualified workers but couldn’t find them to fill jobs.

Back in 2018, this was attributed to the Trump tax package passed earlier in his term, where maybe that attribution was erroneous – that inflation wasn’t likely to spike because the economy was reaching full capacity, there were signs of inflation due to labour shortages.

The labour market shortage had been brewing for the previous decade already, and COVID has since made it worse.

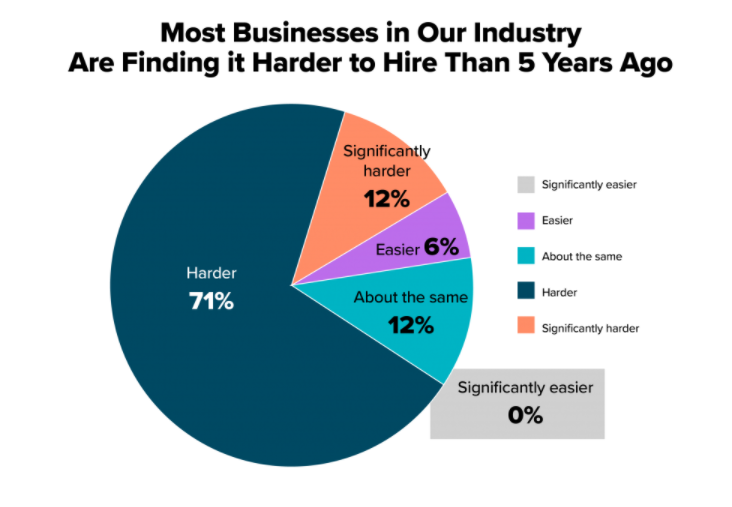

Source: US Chamber of Commerce

Working Age Population

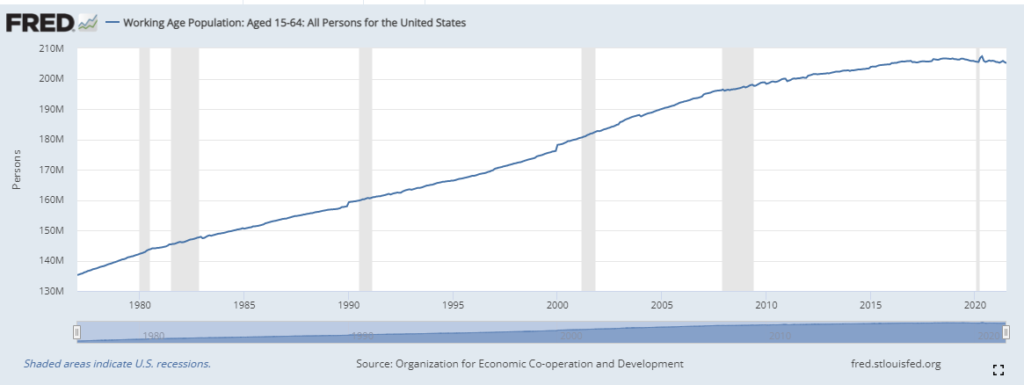

The next item that’s worth considering is that maybe it’s a change in the overall size of the population or maybe an immigration issue in the USA.

That analysis sort of informs us where we can see in 2018 the USA’s working age population began go trend downwards, at a time when a significant amount of Baby Boomers had turned 65 and were retiring.

Source: US Federal Reserve, OECD

This marginally explains why labour may be becoming scarcer but hardly tackles the issue.

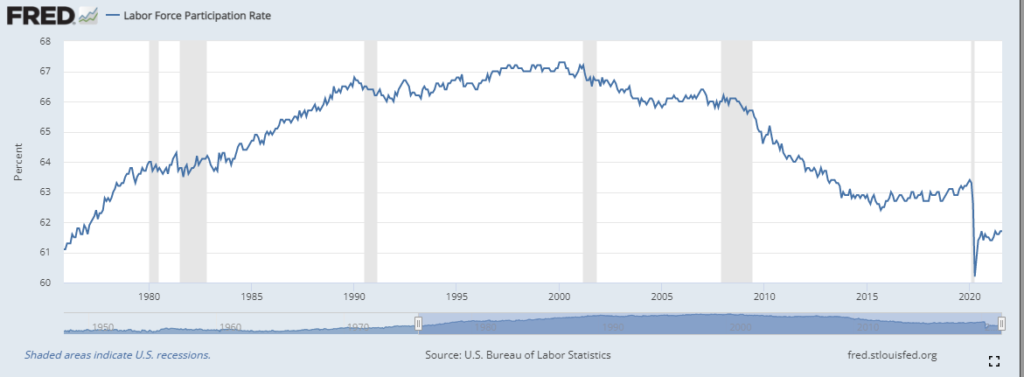

A better way to look at it would be to look at the participation rate of the labour force, analysing how many people are working or if unemployed are looking for jobs within the working age population.

The answer is that over the past 10 years, the US participation rate is dwindling as less, and less people participate in the economy.

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

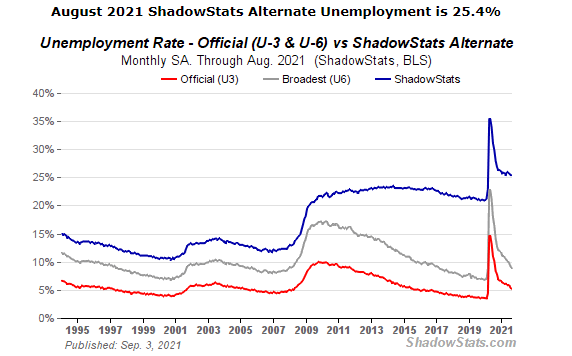

As a sidebar, it’s worth noting that the way we calculate employment has changed over the years, where these changes obfuscate some economic realities that would otherwise be apparent to all of us.

Take for example our employment ratios.

Because we only count people working or actively looking for work, our unemployment ratios are much lower than if we calculated them as a percentage of the working age population.

The following graph highlights this, where the blue line uses this original unemployment methodology, and the red line is the current US unemployment rate.

Source: ShadowStats.com

Criminal Records

Coming back to my opening remarks about criminal record, I recently found out that a person in the US that is found or pleads guilty to a crime has that show on their permanent record for life, unless the record is expunged, which is very rare.

Whereas in Australia, according to the Australian Federal Police, a criminal record will stay on your permanent record for 10 years if recorded as an adult, or for 5 years if recorded as a minor.

This nuance makes a world of difference to our two country’s labour markets as it helps to explain why the US has such high levels of people of working age, but not working nor interested in working.

Why?

There are over 24 million felons in the USA according to a 2019 Senate Joint Economic Committee report authored by Dr Nicholas Eberstadt, who is also author of 2016 book “Men Without Work”.

In this report Dr Eberstadt details the puzzling number of prime-aged (mostly men) who have disappeared from the US labour force, due to many problems such as poor education, opioid abuse, job outsourcing overseas, divorce and having a criminal record.

To quote from the report:

“This single variable also helps explain why the collapse has been so much greater for American men than women and why it has been so much more dramatic for African American men and men with low educational attainment than for other prime-age men in the United States.”

Life Issues This Creates

Having a criminal record in the USA creates many impediments to living a normal life, where in many states you can’t even rent an apartment or apply for a loan to buy a property because you’ll need to disclose that you were once a felon, for the rest of your life.

This is the same when applying for most jobs in most states, creating a sub-culture and sub-economy for people working cash-in-hand jobs or simply not working to try and get by.

In some cases, I imagine, it creates a cycle where former felons may reoffend, reverting to former lifecycles to make ends meet…whereas if this situation wasn’t the case and the US had a system akin to Australia’s, they may never regress.

Untapped Talent

This predicament was also detailed in a recent book by US banking strategist Jeff Korzenik “Untapped Talent”, where the bank found their customers had issues hiring people because of drug abuse – not illegal (black market) drugs – but pain medications.

The way that Korzenik explains it:

- The US rebound from the GFC was depressed because of a lack of labour force participation sapping “economic vitality”, making this cycle different from previous cycles

- The GFC created long-term unemployment which gave rise to the opioid crisis, only exacerbated by the incarceration/recidivism cycle

- This reinforces the feedback loop where many of the 24 million plus individuals are trapped and unable to break the cycle and find meaningful employment and increase their wages and purchasing power

Where it becomes almost impossible for the “slack” within the US economy to diminish.

Mental Take-aways

This may be an issue to ponder over the coming months and years, as we recognise that the US economy will grow well below their potential in the coming decade, without an offsetting amount of productivity gains, immigration, technological innovation or borrowing.

An issue, where the obvious answer would be for the USA to adopt a similar legal treatment as Australia and no longer displaying felony status on a permanent record >10 years later.

Sounds simple, but I have my doubts that this will change any time soon.

Hence, we can project that the coming years -> decade will have slow US economic growth unless funded by a corporate debt binge or a new technology that far enhances current productivity.

This will happen whilst US technology companies continue to drive their equity markets and grow in market cap.

Where their labour force participation rates slowly decrease, and the US economy fails to “run hot” and have sustained inflation over the medium-long term, because of the abundance of “Untapped Talent”.

The views expressed in this article are the views of the stated author as at the date published and are subject to change based on markets and other conditions. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Mason Stevens is only providing general advice in providing this information. You should consider this information, along with all your other investments and strategies when assessing the appropriateness of the information to your individual circumstances. Mason Stevens and its associates and their respective directors and other staff each declare that they may hold interests in securities and/or earn fees or other benefits from transactions arising as a result of information contained in this article.