Australia’s economy has fared relatively better than most other Western economies throughout the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

This is due to many factors: our isolation being an island nation that is far from many other global trading hubs; fiscal and monetary policy support; and our established industrial and mining sector, where minerals and resources trade was able to continue while exporting of labour capital (education, tourism, services) was restricted.

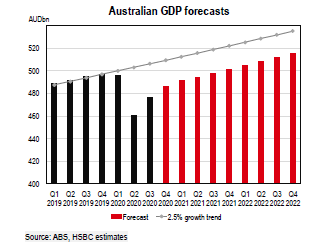

Because of this relative outperformance, Australian GDP likely contracted less than other nations in 2020, with the figure to be published on March 3rd. The IMF expects an average contraction of 5.2% across developed nations and likely Australia’s economy only contracts 2-3%.

As we move into calendar year 2021, we expect that our extended economic outperformance will be predicated by COVID-19 vaccine rollouts and low community transmissions, state and regional lockdowns (hopefully none), and the return of the Australian consumer and our domestic labour market.

The Next Phase

Our economic recovery is already underway as – at time of writing – our economic data is improving and local transmission of COVID are receding.

COVID-19 delivered our largest economic contraction since the Great Depression, ending our 114-consecutive quarterly (28.5 years) run without a technical recession.

However, while our economic activity is lifting from a low base, our growth is forecast to remain below trend at a lower trajectory for the coming years.

The RBA certainly looks at this, as there is now a larger differential between our potential economic output and our realised economic output – known as an output gap.

The size of this output gap is critical in assessing whether our economy will overheat, as until the gap closes, we’re unlikely to see sustained higher consumer prices (inflation).

The Australian Consumer and Mobility Data

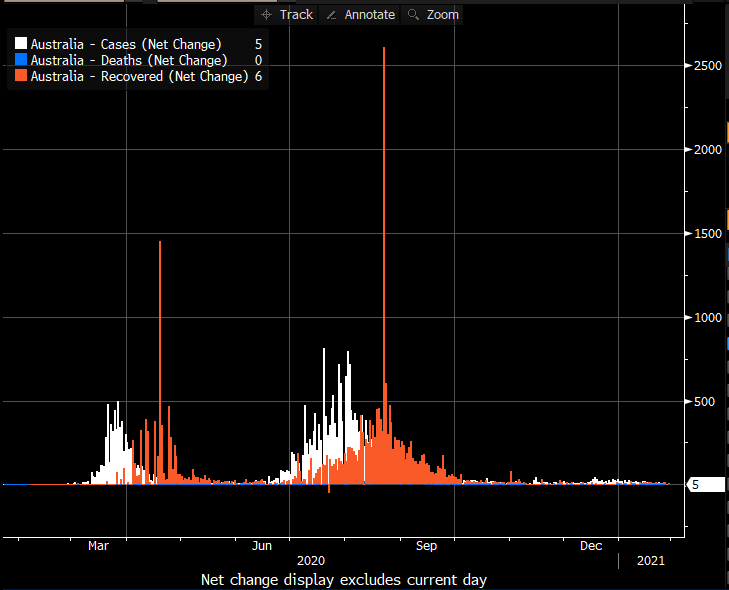

The net change in domestic COVID-19 cases is now small, though our Commonwealth and State governments are worried about a sudden rise of cases if/when the latest COVID-19 strain identified in the UK in December emerges locally.

Source: Bloomberg

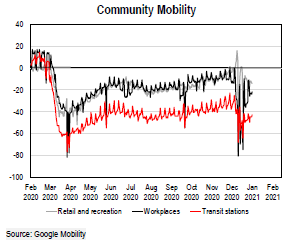

While new cases have subsided, mobility data does not yet show that life has returned to normal, as evidenced in government health restrictions on community gatherings.

Community mobility will likely pick-up as vaccines are rolled out to the Australia population, starting this week.

Australian authorities have purchased:

- 10mio doses of the Pfizer vaccine

- 53.8mio doses of AstraZeneca (will be manufactured onshore)

- 51mio doses of Novavax

- Lastly, we’re also a member of the COVAX facility which allows access to nine different vaccines if the clinical trials are successful

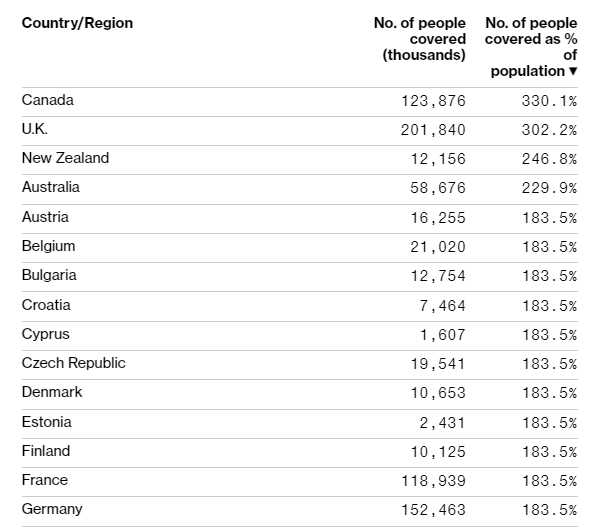

In terms of overall coverage, we have 58.676mio doses of the vaccine available to us this year (assumes no manufacturing issues), covering 229.9% of our population, top five in the world for coverage.

It should be noted that each person needs to take TWO doses of the vaccines, roughly a month apart, which effectively halves the total doses to approximately ~115% of population coverage.

If you’re after daily updates, I recommend Bloomberg’s page available here.

Source: Bloomberg

As of 25 January, our Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) has granted provisional approval for the Pfizer vaccine. If you’re interested in more details regarding the vaccine, the above TGA hyperlink provides access to a range of source documents that are well worth reading.

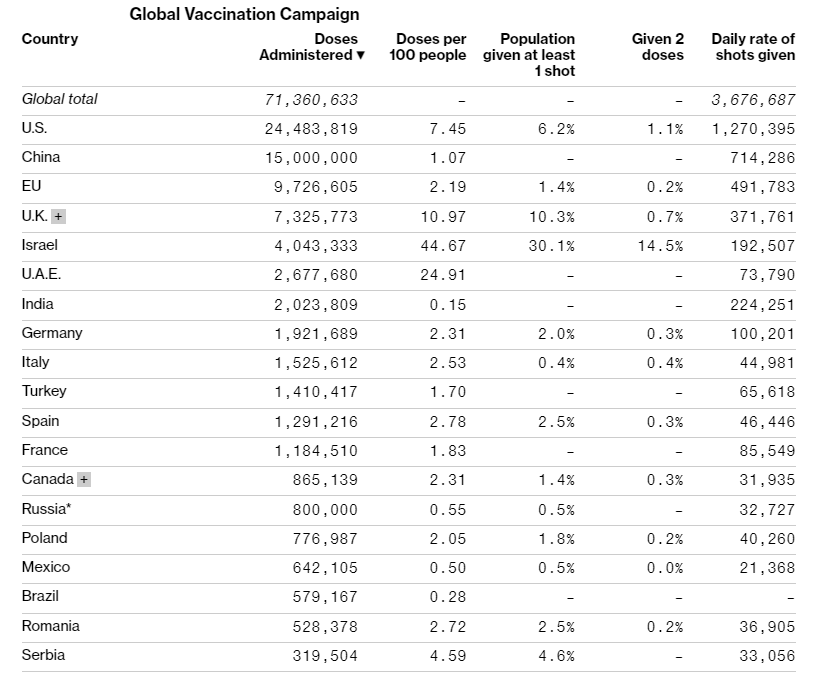

If you are also worried about the haste in which stage 1-3 clinical trials took place, we note there has been over 72mio vaccine doses administered across 57 countries at this point, roughly 3.5mio doses a day on average.

In this regard, we’re off to a slow start compared to many other nations (we haven’t even started), not even making the top 20 list:

Source: Bloomberg

Labour Markets

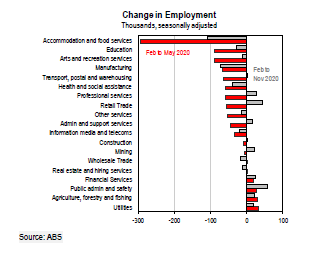

What this translates into is industry sectors that are more sensitive to mobility data and their ability to conduct and transact business.

While employment has bounced back sharply, services sectors have lagged.

In particular, tourism, food and beverage, education, manufacturing, transport and social assistance sectors.

However, while in absolute job numbers we’re close to ~100k extra persons unemployed compared to pre-pandemic levels, the proof is in the pudding where full-time workers have been reemployed as part-time or contract workers, with less pay and benefits.

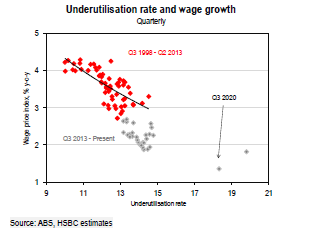

Hence, wage growth is expected to remain stagnant for 2021 with more than half the labour force experiencing wage freezes, and labour underutilisation will be historically high.

For example, we’re currently in the bottom right hand corner of the below chart – we want to be in the top left (red) quarter.

Consumption and Savings

Our economic recovery will also rely on household spending and a reduction in the increased savings of institutions and households.

Interestingly we have spent a larger portion of our net disposable income on household goods and food, and less on clothes, restaurants and cafes – which makes intuitive sense really.

Cross-border Challenges

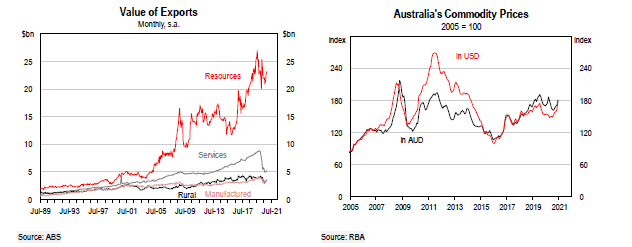

Over the last thirty years, Australia has derived a large portion of its growth and prosperity on the back of migration, tourism and exporting of resources and education.

While resource export volumes have been strong and commodity prices high, closed international borders have weighed on our other cross-border industries.

Even with COVID-19 vaccines rolling out across the globe and “herd immunity” on the horizon over the next 12-18 months, we will need international borders to reopen which isn’t expected for at least 6-12 months and even then, gradually.

Closed borders mean more reliance on resource and materials exports, compared to more consumer-led sectors such as education and tourism.

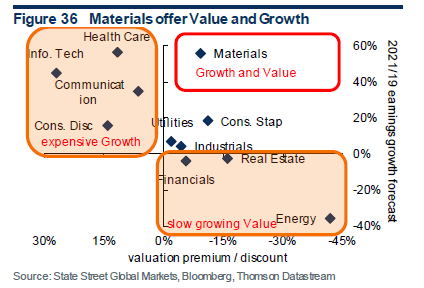

This may also be seen in relative out-performance of relevant industry stock categories relative to the lock-down sensitive sectors/industries.

I.e. miners could outperform tourism stocks during this period, all else remaining equal.

In particular, I wish to share the below chart from State Street, highlighting that USA materials sector exhibiting growth and value – similar to Australian domestic market – and ticks the box on not being affected as much by mobility restrictions compared to consumer discretionary, tourism, healthcare etc.

Fixed Income

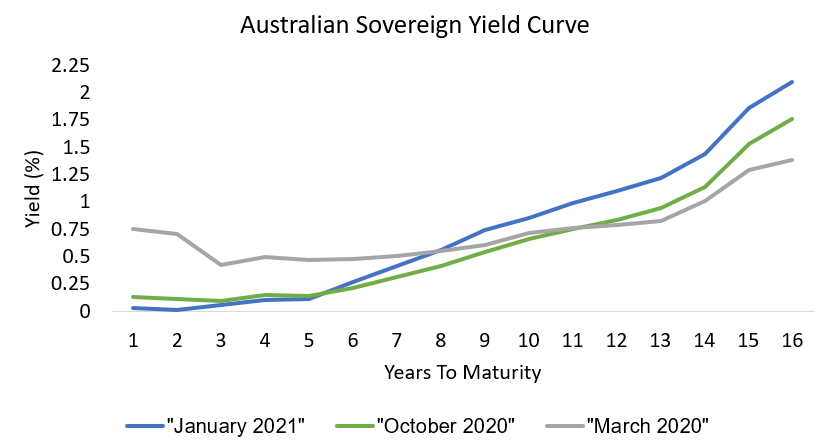

Our domestic market has seen medium to longer term government bond yields rise, pricing in higher inflation expectations.

This has seen the yield curve “steepen” in gradient (blue line) relative to our yield curve in October (green line) or March 2020 (grey line).

Source: Mason Stevens

The short end of the yield curve is anchored by RBA policy of the Overnight Cash Rate (OCR) at 0.1% and their 3-year government bond target yield also at 0.1%.

However, the RBA is likely to underwhelm expectations of higher cash rates and sustainably higher bond yields, as mathematically, the RBA OCR would need to rise to ~1.5% within the next 3-4 years in order for the cash rate to average over 1.0% over the next 10 years – where our current 10year government bond is trading.

Moreover, when we factor in the prolonged nature of the economic output gap and resulting below RBA target inflation (2-3% p.a.), the RBA will be effectively on hold for a sustained period, though they may make tweaks to their asset purchase program.

Hence, we foresee this sell-off to be contained in the medium part of the yield curve, and for government bonds to rally to lower yields than present.

AUD currency

The AUD/USD exchange rate is at 76.5c at time of writing, with the market consensus that it’ll move higher.

For example, HSBC has a target of 81c by year end, Citi 80c, Nomura 80c+ >> all higher price targets.

This is based on our AUD having a high beta (correlation) to global growth and recovery, where the “reflation” will be seen through rising commodity prices as industrial sectors are first to recover.

This is part of the reason why we share a view of persistently low RBA target inflation, because as our AUD rises based on export volumes and trading, this lowers the price of foreign goods that we purchase, that are part of the Consumer Price Index (CPI).

Following RBA Board member comments in recent months (Lowe, Kent, Debelle), we would say it’s unlikely for the RBA to jawbone the AUD lower when its coupled with fundamentals and rebounding export volumes.

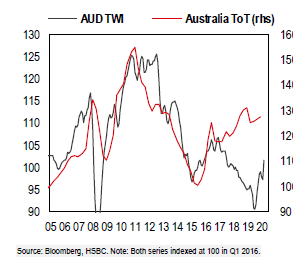

In fact, our Terms of Trade (ToT) (red line) argues that AUD (black line) is undervalued and should be higher.

This is in contrast to Dec 2017-Jan 2018 where AUD rallied from 75 to 80c against the USD, where the rise was not predicated by a corresponding boom in export volumes.

Summary

Australia’s economy has fared better than most Western economies and that’s a trend we believe will continue in 2021.

That may not necessarily translate into out-performance of financial assets relative to other economies; as we established in December, financial markets are more affected by perception than fundamentals at present.

However, Australia will likely be associated as being a source of relative safety compared to global asset markets that have more protracted issues due to COVID. As such, Australia may become a “value” allocation in 2021, as asset allocators rotate away from “growth” assets with higher valuations/multiples, into assets with more realistic valuations/multiples.

The views expressed in this article are the views of the stated author as at the date published and are subject to change based on markets and other conditions. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Mason Stevens is only providing general advice in providing this information. You should consider this information, along with all your other investments and strategies when assessing the appropriateness of the information to your individual circumstances. Mason Stevens and its associates and their respective directors and other staff each declare that they may hold interests in securities and/or earn fees or other benefits from transactions arising as a result of information contained in this article.