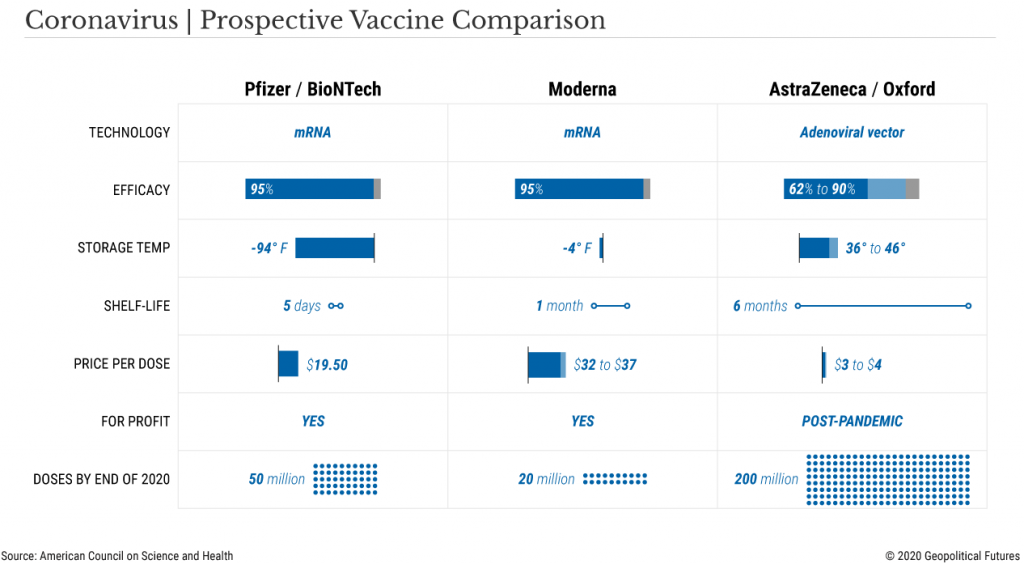

The American pharmaceutical firm Pfizer, in collaboration with German firm BioNTech, surprised the world when it announced their coronavirus vaccine showed 90% efficacy in preventing COVID-19.

Days later, another American firm, Moderna, announced their vaccine has nearly 95% efficacy.

Shortly after this, AstraZeneca announced that its vaccine was 62 to 90% effective, depending on the age of the recipient.

There is no global standard vaccine emergency use authorisation, though in the USA it is 50% efficacy and in Australia approval is subject to the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) assessment.

For those interested in more details, I suggest our Commonwealth Department of Health summary or their in-depth planning document.

In the USA, all three drugs pass the 50% efficacy threshold, a benchmark most observers weren’t expecting the vaccine candidates to outperform.

As such, the results were a pleasant surprise that excited financial markets and saw governments around the globe jumping over themselves to buy allocations for their populations.

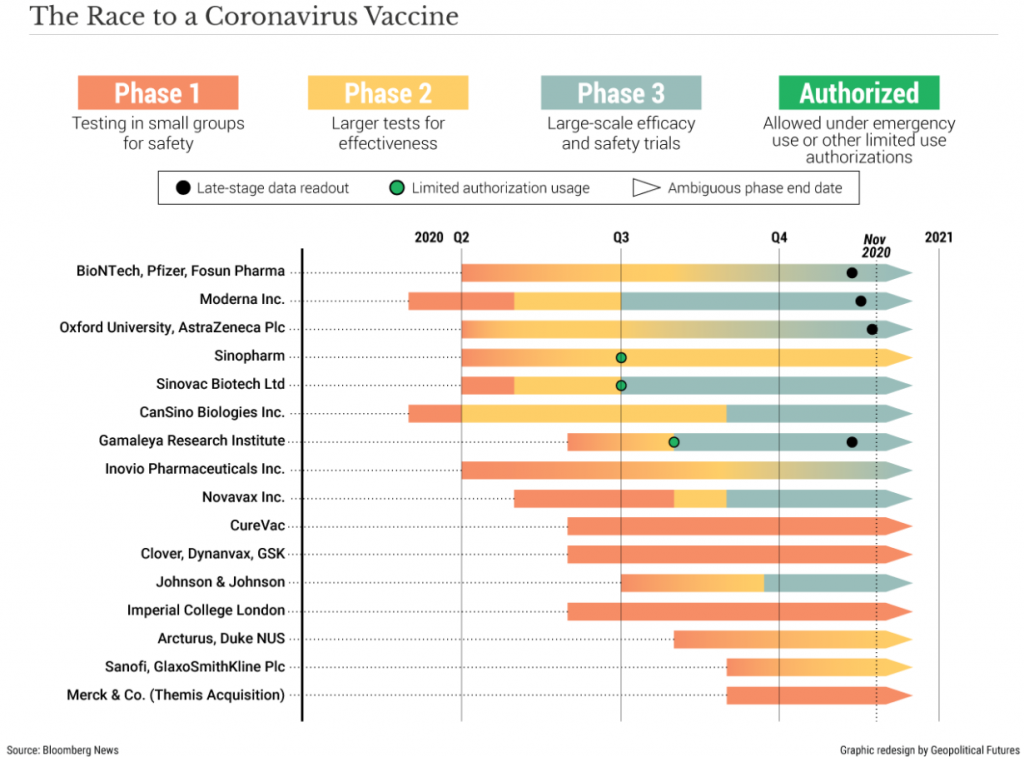

The magnitude of the accomplishment from these pharmaceutical companies cannot be overstated, as typically, the timeline from inception to regulatory approval of a new drug is ~10 years.

And that is just for approval.

After receiving approval, pharmaceutical firms then organise mass manufacturing and distribution, which again can take years.

However, thanks to government programs such as ‘Operation Warp Speed’, expedited regulatory approval and unprecedented global cooperation, the first batches of COVID-19 vaccine from a trustworthy source will be delivered in less than one year – start to finish.

Holding our horses

Even so, we shouldn’t get ahead of ourselves as it will be months before the vast majority of people can receive a dose of the vaccine.

Though approval should take roughly 3-4 weeks as government experts pore over the data, the process could take longer.

According to Doctor Henry Miller of the Pacific Research Institute, government regulators have concerns about consistency in production methods, that ensure batch after batch of vaccines meet quality control measures, such as potency and purity.

A timeline of sorts

By the end of December 2020

- Moderna plans to have 20 million doses available

- Pfizer plans to have 50 million doses available

- AstraZeneca will produce 200 million doses

Under this timeline, some people will be receiving their first vaccine dose by the end of the year.

But please be aware, in all three of these company’s vaccine doses, they require two shots one month apart, which effectively halves the number of people who can receive the 270 million doses to 135 million – unless production ramps up in the short space of time.

By the end of 2021, current forecasts are for one billion doses to be available from all companies combined, allowing 500 million people to receive both their 1st and 2nd instalments.

The distribution dilemma

Manufacturing enough doses is just one of the hurdles, another is distribution which is a two-fold problem.

- Modern’s vaccine must be kept frozen during long-term storage and shipment, Pfizer’s’ vaccine must be kept at -70’ Celsius (-94’ Fahrenheit)

- It’s not ethically or strategically clear whom should receive the vaccines first.

The cold chain

The reason our grocery stores contain relatively fresh food from across the planet is because of a logistic process known as the “cold chain”, a series of refrigerated containers that allow perishable food to be shipped without spoiling.

Many drugs and especially vaccines and antidotes require the same thing.

However, Pfizer’s vaccine which consists of an unstable molecule called RNA, requires storage at -70C, a temperature that generally only research laboratories can attain through deep freezer use, which pharmacies and hospitals do not have.

Pfizer’s solution is to provide special containers that can be packed with dry ice to maintain the requisite temperature, but once the vaccine has been removed and placed inside a regular refrigerator, the shelf life is 5 days.

The Moderna vaccine can be stored and shipped at -20C (-4F) and has a shelf-life of 30 days in regular refrigerators, thus posing a smaller logistical challenge.

AstraZeneca’s vaccine is the easiest of the three to distribute, since it can be shipped at regular fridge temps and kept on the shelf for six months (but remember, lower efficacy rate).

Which countries get the vaccine first?

The question plays out at the international level initially, with countries that made the first purchase orders the first to receive them.

For example, the European Union was among the first to secure 200m doses of Pfizer’s vaccine with an option to purchase 100m more.

Japan secured 120m doses, the UK 30m doses and the USA 100m doses with an option for 500m more.

Pfizer simply cannot meet that demand even by the end of 2021, which could mean these countries fight among themselves over who gets what batch and when.

In Australia, we hedged our bets and secured initial doses of four of the most promising vaccine candidates – knowing one or all of them may not prove effective, but ensuring Australia had sufficient vaccine doses secured for our population size.

Four vaccines Australia is getting:

AstraZeneca/Oxford University – 33.8m units during 2021

Novavax – 40m units in the first half of 2021, with one of their clinical trials taking place in Australia

CSL/University of Queensland – 51m units, with hopes for availability in mid-2021. Their Phase 3 trials are under way this month (December 2020) in Brisbane.

Pfizer/BioNTech – 10m units secured, available from March 2021.

It should be noted that companies are under pressure to release vaccines to their “home” country first, though many of these companies are multinationals entities that call several countries home.

We’re lucky we have a local candidate (CSL/Uni of QLD) which calls Australia home.

Which countries get the vaccine second?

The initial vaccine recipients are all rich countries.

While the economic powerhouses duke it out for the first round of COVID19 vaccines, the rest of the world will wait for their jabs.

Many of these poorer countries do not possess the cold chain required to deliver the vaccine at sub-zero temperatures with poor infrastructure and unreliable electricity.

These gaps in the cold chain will destroy the vaccines efficacy and make current vaccines untenable.

But which people get the vaccine first?

This is an ethical dilemma for most countries as there are internal factors that vary vaccine distribution.

In Australia and the USA, its which states will receive the vaccines first, and then which parts of each state. Capital cities? Rural areas with less access to healthcare? The elderly and at-risk population first? Children first?

In Washington state USA, they already have made the strategic decision to rollout the vaccine to #1 frontline health workers, armed forces and at-risk population, #2 general community, #3 filling any gaps that may have been missed.

Using this strategy, I still have an un-answered question, “Who gets the less effective vaccine?”

Statistically speaking, each person would rather take a dose with a higher efficacy and thus the Moderna or Pfizer vaccine, over the AstraZenca or others.

The world’s biggest race

Whilst this paints a dim picture for the poorest of nations, whom are likely to receive the vaccine last, there is room for optimism.

It is likely that other vaccines going through clinical trials, like AstraZeneca’s, will not require the extreme cold chain that other vaccines (such as Pfizer) require.

Likewise, companies such as AstraZeneca have pledged to forgo profiting off their vaccine sales and are working with NGOs and charities around the world to provide vaccines to developing countries.

Also, we should to be optimistic that the questions regarding the vaccine have shifted from if to when.

As such, for most of us in Australia, 2021 seems to be a year for improvement; where our economic and social conditions are partially repaired, with vaccinations are only months away.

The views expressed in this article are the views of the stated author as at the date published and are subject to change based on markets and other conditions. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Mason Stevens is only providing general advice in providing this information. You should consider this information, along with all your other investments and strategies when assessing the appropriateness of the information to your individual circumstances. Mason Stevens and its associates and their respective directors and other staff each declare that they may hold interests in securities and/or earn fees or other benefits from transactions arising as a result of information contained in this article.