RBA Governor Philip Lowe attended the Committee for Economic Development of Australia (CEDA)’s annual dinner on Tuesday evening. The topics he spoke about are not only important to us for their investment implications, but also to understand what policies one of our nation’s largest and most influential institutions are enacting in response to COVID and the economic trends affecting Australia.

Listening in, I thought Lowe presented a pragmatic view of the economy, though noticeably more negative when compared to Treasurer Frydenberg’s comments in his Budget address.

For those interested in Lowe’s direct remarks, you can view them here, otherwise please enjoy my summary and observations.

Our labour market, employment and spare capacity

It is paramount to remember that the RBA views our economic potential versus the current or realised growth.

The difference between potential and actual economic output is called an “output gap” or “slack”, both referencing a sub-optimal economy where there’s room for improvement.

Right now, there’s plenty of labour slack and a historically high economic output gap largely due to COVID, although it was present before COVID to a lesser extent.

The RBA has been seeking to address this gap for many years by maintaining relatively accommodative monetary policy, where they push the Australian domestic economy to “full employment”.

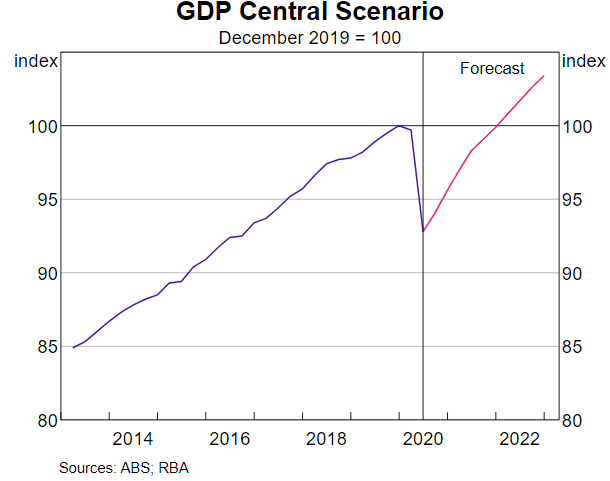

Lowe commented that this will be a slow and long recovery and that GDP will not reach pre-pandemic levels until at least the end of 2021, and that our actual GDP may not hit 2019 potential GDP for years (and probably a decade).

For reference, it took 11 years post 2007/2008 GFC for US GDP to reach 2007’s potential GDP.

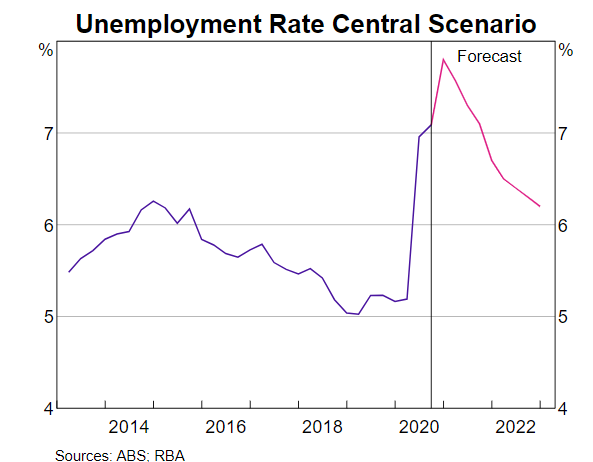

By the end of 2022, the RBA forecasts that the unemployment rate will remain above 6%, let alone near the 5% unemployment rate we had in Q4 2019.

Until the unemployment rate nears full employment, the RBA does not foresee broad based inflation, and will likely be not hiking interest rates.

Population growth

Due to closed borders this year, population growth is expected to be just 0.2% y/y, the lowest since 1916 when soldiers were leaving our shores to fight in WW1.

Population growth has averaged 1.5% per annum and has added 0.5 to 1% to economic growth each year or approximately 20-30% of overall economic growth.

Without population growth, our economy has barely been growing.

If we were to ignore debt as well in order to gauge productivity enhancements, our economic growth has been negative.

Therefore, productivity growth has been minimal and part of the reason why we were critical of the latest Commonwealth Budget.

Property

Across the commercial property space, conditions vary hugely from rising vacancy rates in CBD office space, difficult conditions in retail space and high demand for warehouses and logistics facilities supporting industrial property.

These were broad comments but help separate the property winners and losers during 2020.

Risk aversion

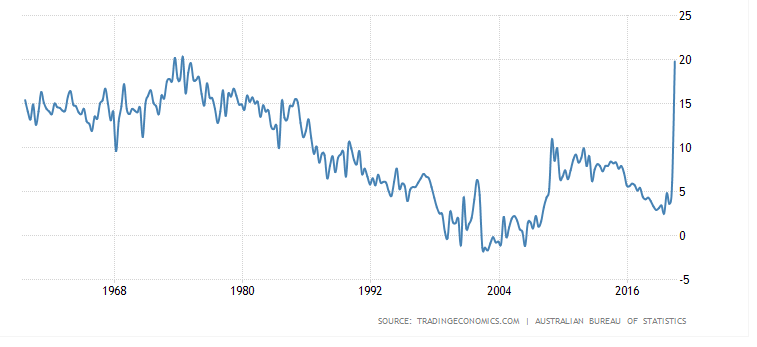

Governor Lowe expects understandable caution for a time, affecting spending and saving decisions.

Lowe says it’s important to not be too risk averse, something you may have seen mentioned more and more lately as “economic scarring”.

This sums up the notion that Australians are experiencing a behavioural change due to the negative psychological effects of COVID, and are changing their spending patterns to be more defensive, with more money allocated to savings.

In passing, Lowe also mentioned that the low returns on cash accounts and term deposits is driving a “search for yield”.

The below chart depicts Australian household savings since 1960.

Source: Trading Economics

Role of fiscal policy

Fiscal policy has taken on a greater role to stabilise the economy as entirely appropriate within the two-part fiscal strategy.

The 1st part is to support the economy through the pandemic and foster a recovery (or rebound).

The 2nd part is to stabilise the economy over the medium to longer term and reduce debt once the unemployment rate is comfortably below 6%.

Tying this back to my earlier commentary on the labour market, this means that the Commonwealth government should not be attempting to meaningfully reduce our nation’s government debt for at least 3-4 years, and until a 6% unemployment rate can be attained.

Any attempt to reduce our debt in the meantime will likely slow the economic recovery.

Monetary policy

The RBA has changed their approach somewhat to inflation targeting, to rely on actual inflation data rather than forecast inflation expectations to guide policy given the large changes in inflation dynamics wrought by globalisation, technological innovation and the current pandemic.

I heard this and had to laugh; this is the RBA all but admitting their forecasting models do not accurately capture inflation expectations and explains why they’re underachieved their 2-3% inflation target over the last ~10 years.

In essence, this means inflation will need to average 2-3% sustainably before they tighten policy (no time soon).

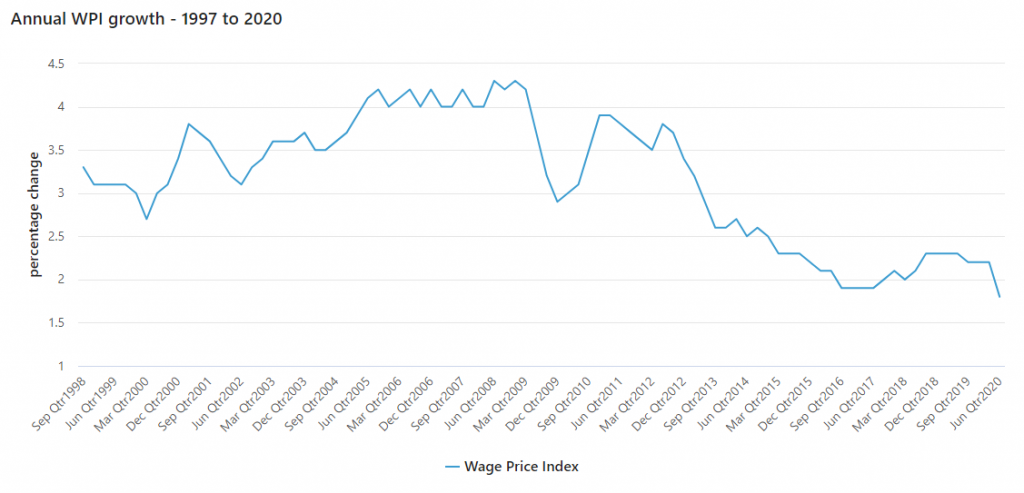

Wages

For inflation to hit the RBA’s target, wage growth will need to increase materially by 3.5% to 4% per annum, which is “incredibly unlikely” (Lowe).

Lowe noted that the Bank will be pleased if wages were growing at 2% per annum, something that hasn’t been sustainably the case for some time….let alone 3.5% to 4%!

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics

Trust

A very qualitative topic, but I appreciated that Lowe mentioned this.

The RBA is pleased by the political class, our institutions, regulators and bank and how they’ve all responded to the crisis.

This has fostered trust between these institutions and agencies and the public.

Trade tensions

China’s growth pick-up post-COVID has influenced commodity prices to the upside and Australia is well-placed even though certain product lines have been affected by trade tension.

Falling income for savers

Lowe noted that he receives letters all the time regarding falling income for savers and this worries both him and the Bank.

I note the RBA often speaks about this in their Statements of Monetary Policy (SoMP) that are released quarterly on their website.

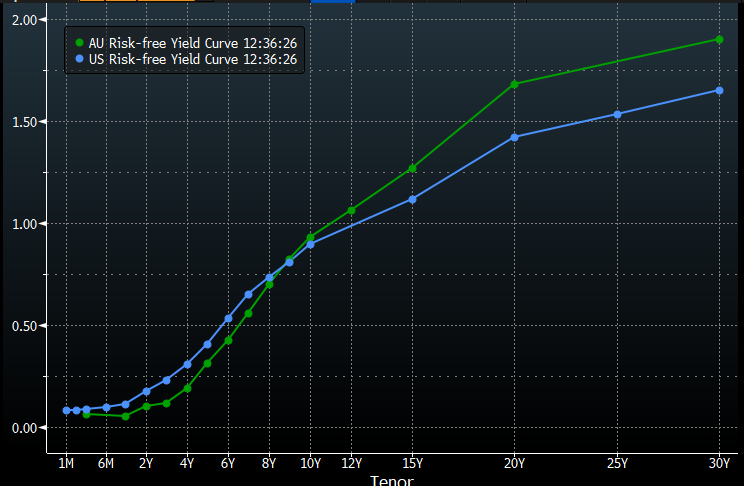

Negative interest rates?

Negative interest rates are still “extraordinarily unlikely” as they adversely affect spending, since savers need to save more in the face of declining rates of return on deposit income, as seen through Japan and Europe.

The RBA would only consider negative interest rates if the US Federal Reserve took their policy from 0% – 0.25% at present to -0.5% or -1%.

At current pricing, the market has a positive yield curves for both the US (blue) and Australian (green) bond market.

Source: Bloomberg

A negative cash rate would mainly be to depreciate our currency, the AUD, relative to other currencies.

Closing comments

This all came across as dourer than what people would like to hear, though realistic.

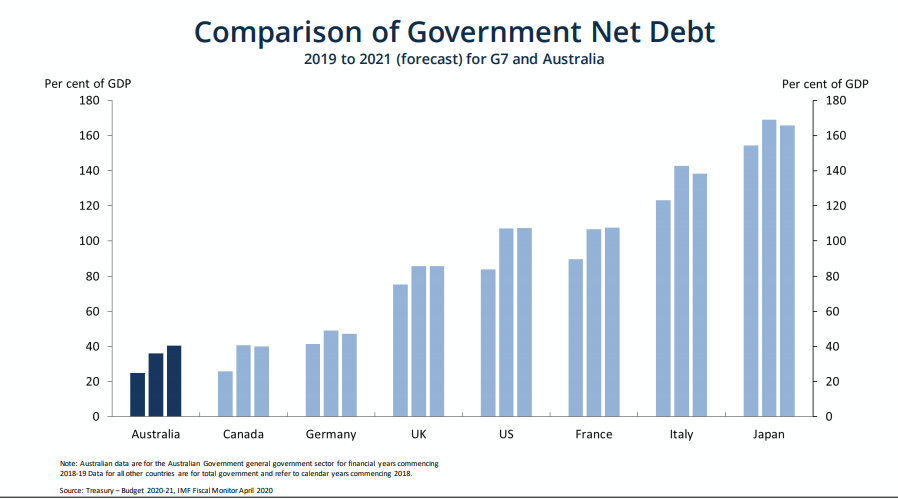

It is worth reminding ourselves that the Commonwealth government will be required to assist the rebound from the pandemic, and they have the relative strong balance sheet that further enables them do to so.

However, also need to be aware that our labour market is the key indicator for both the RBA and for us to track the progress our overall economy makes.

It is likely we will require immigration to lift economic growth, where productivity growth is missing and not adequately addressed in Commonwealth and State budgets.

We should remain steadfast that we are all in this together and that COVID-19’s effects will linger within our economy for some years to come.

The views expressed in this article are the views of the stated author as at the date published and are subject to change based on markets and other conditions. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Mason Stevens is only providing general advice in providing this information. You should consider this information, along with all your other investments and strategies when assessing the appropriateness of the information to your individual circumstances. Mason Stevens and its associates and their respective directors and other staff each declare that they may hold interests in securities and/or earn fees or other benefits from transactions arising as a result of information contained in this article.