Governments’ budget proposals are just that – proposals – meaning they are subject to amendments. In implementation, they can differ greatly from their original plan.

They are based upon assumptions such as tax rates, unemployment figures, government revenue (tax receipts), economic output to name but a few and are predicated by various outcomes from several factors: COVID, household consumption, market interest rates, etc.

There are so many variables and assumptions, that Paper 1 of the Budget, when published in early October, came in at 370 pages.

The expenditure proposals certainly were not that exhaustive to warrant 370 pages. They made up less than one third of the briefing documents (about 95 pages), and costings aren’t published until Paper 2!

The Budget papers are so long because there are many changing variables involved. In many circumstances, the Budget numbers are obsolete less than a week after they are publicised.

This year is no different.

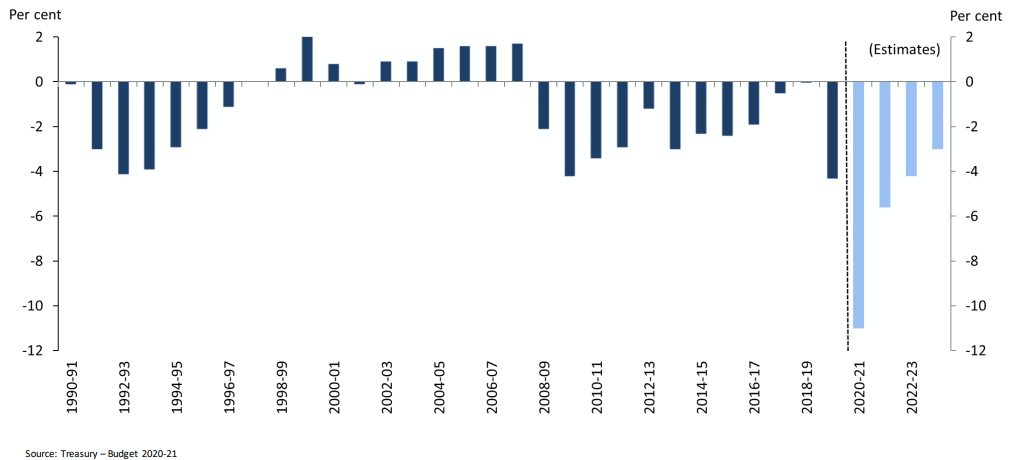

The Commonwealth’s proposed 2020/21 budget deficit was 213.6bln AUD, or 11% of Q2 2020 GDP.

This number is already looking too small.

Government debt issuance – more “stimulus” than forecast

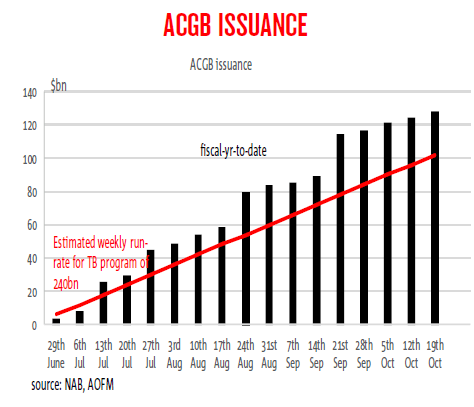

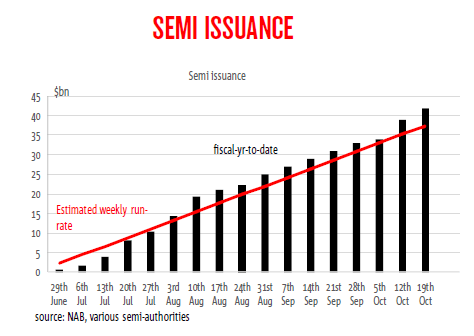

The current run-rate of debt issuance out of both AOFM and State borrowing authorities is greater than the required run-rates.

From Treasury and AOFM, they have issued more than 20bln AUD of Australian Commonwealth Government Bonds (ACGBs) ahead of schedule, to meet their funding target of 240bln for this financial year.

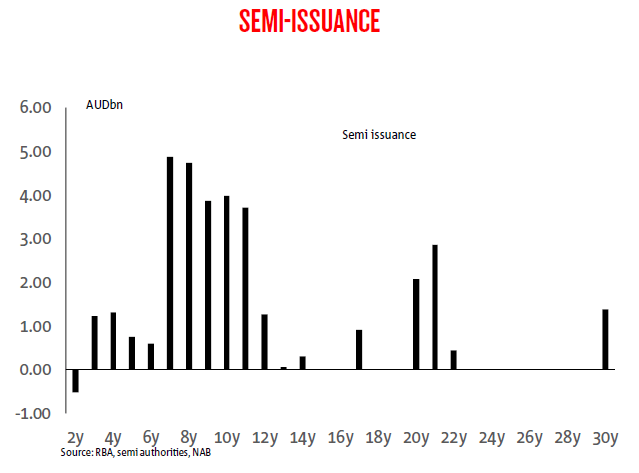

And in the State government borrowing authorities’ case (“semis”), the States are also ahead of required run-rates by ~5bln AUD.

This can reflect different realities.

#1 Government debt issuers may be running ahead of schedule to take advantage of advantageous yields

This is unlikely, as Australian interest rates and bond yields are forecast to be lower for longer, and more advantageous issuing conditions can be foreseen in the future.

This is also unlikely because the debt issuers would need to pay the costs of the debt (coupons) when the funds are not required for differing periods of time. More likely, they would issue short-term debt, such as treasury notes, with shorter maturities to smooth out their longer-maturity bond issuance.

Lastly, the larger-than-usual issuance pipeline has caused longer-tenor bonds to sell-off slightly, as the increase in supply is digested by the market.

If anything, Treasury departments would have sought to avoid this if possible, resulting in slightly lower costs of funds.

#2 Higher funding anticipated than Budgets project

The more obvious answer is that government debt issuing agencies are forecasting higher funding requirements than stated Budget figures and are running above Budgetary run-rates to hit their new and increased issuance targets.

This is my base case and that governments are giving themselves wiggle-room in case COVID-19’s impact is more prolonged and pronounced than expected, and they need to support the private economy with further “stimulus”.

However, this is counter-factual to recent comments from AOFM, with their CEO Rob Nicholl speaking last week and providing the market with their latest chart pack.

In his remarks, Nicholl mentioned that the Government’s forecasts project an improvement in the Budget position in FY 2021/22 and by definition, a reduction in their future funding task.

Below are Commonwealth Treasury’s forecast for yearly budget deficits.

This needs to be overlaid with the possibility that their forecasts change and that more debt is issued now and less in later years.

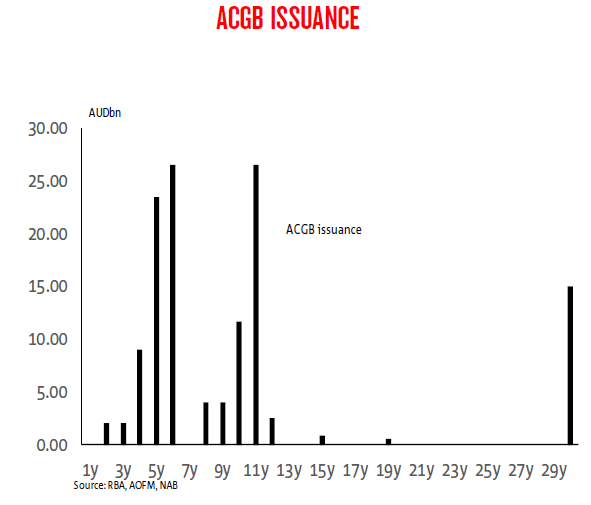

Tenors of issuance

One of our criticisms, though this quickly became a consensus view, was that the Budget as detailed by the Commonwealth Government and Treasurer Frydenberg was short-term and lacking long-term productivity reform that allows Australia to grow out of the recession, but also meaningfully reduce the extra debt load undertaken during 2020.

Without substantial and sustained economic growth, debt reductions will need to be undertaken through cost reductions, which are harder to implement than growth increases and policy initiatives.

There is a negative connotation associated with cost reductions which can take the form of increasing taxes (increases government revenue), or reducing social welfare, unemployment benefits, military spending or pension rates.

As such, the debt burden is here to stay and to epitomise this, the debt issued at the Commonwealth government level has been largely short-term (3 to 11 years), which will need to be re-financed yet again when maturing.

Our State governments, however, are more pragmatic and have issued debt in an array of tenors, recognising the need to diversify funding costs over a longer period.

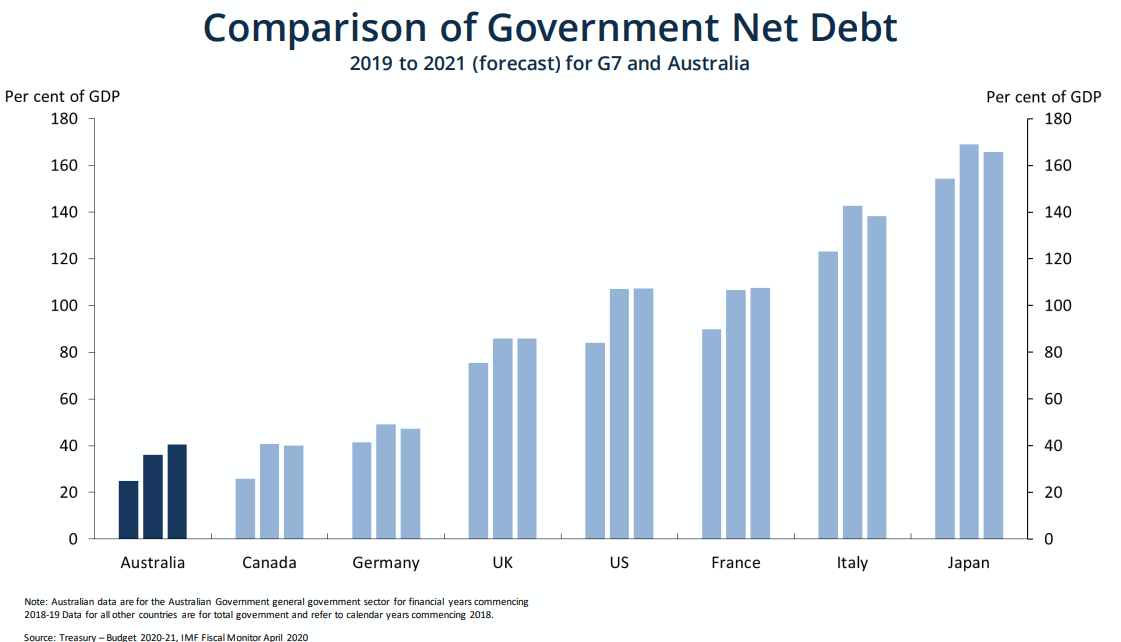

Relative terms

It should be remembered that in contrast to other major nations, Australia’s budgetary position is in better shape, with Commonwealth and State balance sheets in relative better position than G7 equivalents.

Because of this, the higher debt issuance run rate should be put in context that we’ve come from a better starting position than other nations. Moreover, we cannot ignore that COVID has affected Australia to a lesser extent.

As such, government balance sheets maintain capacity to further stimulate the economy if needed, and the extra debt burden should be manageable from a servicing perspective.

It should be also remembered that without sustained growth coming out of the crisis, the extra debt burden is increasingly hard to pay down and reinforces the current low interest rate environment, as debt servicing costs and re-financing operations constrain economic growth for years.

In the meantime, our nation’s debt remains attractive – as we’ve mentioned in other morning missives here, here and here – and any sell-offs from increased debt issuance as the market digest the extra supply are met with more buying from foreign sources, as well as the RBA’s quantitative easing program.

The views expressed in this article are the views of the stated author as at the date published and are subject to change based on markets and other conditions. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Mason Stevens is only providing general advice in providing this information. You should consider this information, along with all your other investments and strategies when assessing the appropriateness of the information to your individual circumstances. Mason Stevens and its associates and their respective directors and other staff each declare that they may hold interests in securities and/or earn fees or other benefits from transactions arising as a result of information contained in this article.