Understanding inflation is crucial to investing because inflation can reduce the value of investment returns.

Inflation impacts all aspects of the economy – be it household spending, business spending, employment rates or interest rates.

Inflation is a sustained rise in price levels of goods and services.

Moderate inflation (say 2-3% p.a.) is associated with economic growth and prosperity, while high inflation is seen as an overheated economy and deflation (negative inflation) is seen as a contracting economy that is struggling to perform.

In the growth stage of an economic cycle, demand increases against the existing amount of supply of goods and services and prices rise accordingly to reflect the higher premium associated with the various goods/services.

This can be viewed from the currency sense, that the purchasing power of your dollars is declining, as they can buy less goods and services compared with previous time periods.

Right now, we have negative economic growth due to the health crisis and isolation policies, where demand for goods and services has declined to historically low levels. At this point, the rate of inflation has dropped, and we are experiencing disinflation or deflation around the globe.

Central banks are responding to this drop-in price levels by increasing the money supply, in an attempt to re-kindle inflationary expectations.

It isn’t working

Central banks are famously increasing money supplies, with their record asset purchase programs (quantitative easing).

The expansion of central bank balance sheets increases the money supply when the bank buys bonds (asset) and simultaneously increases reserves within the banking system (liabilities).

Money Supply 101

There are various measures of the money supply.

For example, M0 is all the current currency in circulation and the broadest calculation of the money supply.

The central bank preferred measures called M2, which includes all cash and coin, but also savings/cash account deposits, money market funds and any certificates of deposit.

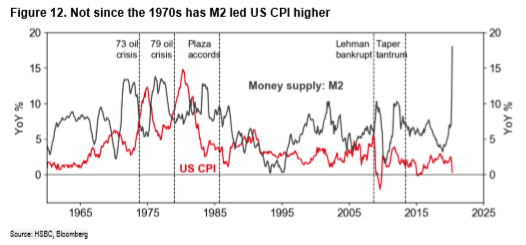

M2 is recognised as the most accurate measure to estimate future inflation outcomes.

Central bank actions

The assumption that M2 increasing leads to inflation increasing is the driving force behind central bank asset purchases, other than the explicit support they’re providing for financial markets’ trading.

However, if we look at the change in M2 versus the Consumer Price Index (CPI) as our measure of inflation, there’s little evidence of M2 growth meaningfully impacting inflation since the 1970’s.

Source: HSBC, Bloomberg

Why it isn’t working

Investors who have watched the QE programs of Japan over the last two decades, the US since 2008 or the European Central Bank for the past 5 years would’ve noticed below-target inflation despite record money supply increases.

The key thing to remember is that these reserves are not strictly part of the money supply.

As we mentioned, the central bank buys a bond and required reserves are a liability allocated to the banking sector.

However, due to cash hoarding and a disconnect between higher bank reserves and lending to the private sector, the expansion of M2 is not influencing inflation. Hence, we shouldn’t categorise these bank reserves as part of the money supply.

This can be empirically proven as bank reserves held at the central bank are part of the monetary base, along with currency in circulation and cash/coin held by banks, that can be converted into hard currency.

However, this conversion will only occur if, and only if, the public wants to hold more currency and withdraw funds from the banking system that are not currency hard in existing currency in circulation. Otherwise, bank reserves will remain locked in the banking system and not add to the public system money supply.

In basic terms, commercial banks are not going to reduce their reserves with the central bank unless they’re able to generate loan growth or buy other assets at sufficient business margins to decrease the reserve balances.

Also, banks need to meet capital requirements of their regulatory ratio the Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR), which is the amount of estimated cash outflow over the next 30 days, accounting for a stressed environment.

Hint: right now, this LCR value is very high given the financial market volatility and increased cash holdings of their banking customers.

Velocity of money and debt servicing

Ultimately, the above leads to no increased velocity of money as the central bank asset purchases do not lead to increased circulation of money within the domestic economy, without sufficient lending to business or households – something the central bank cannot directly influence.

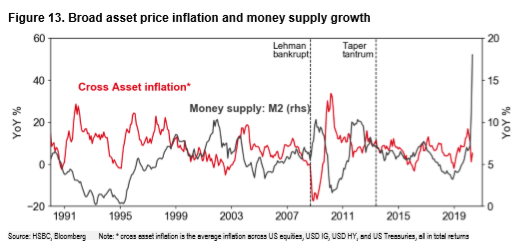

Ergo, little inflation outside of financial asset markets.

Source: HSBC, Bloomberg

Lessons from Japan

All these points do little to explain the lack of inflation in countries such as Japan – and the answer is that the answer is multi-faceted and complex.

Central bank asset purchases do little to help the demographic story of a decreasing working-age population, as Baby Boomer generation transitions to retirement.

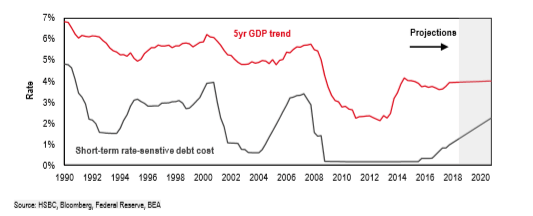

Also, the central bank QE model does not include how current debt levels weigh on future economic growth and requirements to service said debt. This diverts funds away from goods and services, keeping prices subdued, and inflation low.

In fact, while sovereign interest rates have fallen, private sector debt servicing costs are continuing to rise globally as the total debt is growing faster than the blended interest rate of debt declines.

I caveat the above statement as the recent reductions to short-term interest rates have not been factored into debt servicing indicators.

Source: HSBC, Bloomberg

Thinking of better policies

If the “printing press” of central banks was to get into the pockets of consumers this would be a different story.

i.e. if the new money being supplied was to go to consumers, rather than sit as “trapped’ bank reserves, then we may see consumption increase, leading to CPI increases.

QE isn’t inflationary for the general public because the money is stuck in the financial system and boosts asset prices, not goods and services pricing.

As central banks realise this – helicopter money, direct monetary financing (central banks buying Treasury issued bonds) and Modern Monetary Theory become increasingly likely.

Interest rates are likely to stay low for even longer, and there are higher and higher hurdles to future interest rate hikes. Likely, interest rates can not be materially increased without a reduction in debt to reduce debt servicing outlays.

Lastly, it’s become increasingly likely that central banks adopt yield curve control measures (pegging interest rates), something our RBA has already enacted. This means that inflation was to rise, bond yields would be contained and less likely to sell-off.

The views expressed in this article are the views of the stated author as at the date published and are subject to change based on markets and other conditions. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Mason Stevens is only providing general advice in providing this information. You should consider this information, along with all your other investments and strategies when assessing the appropriateness of the information to your individual circumstances. Mason Stevens and its associates and their respective directors and other staff each declare that they may hold interests in securities and/or earn fees or other benefits from transactions arising as a result of information contained in this article.