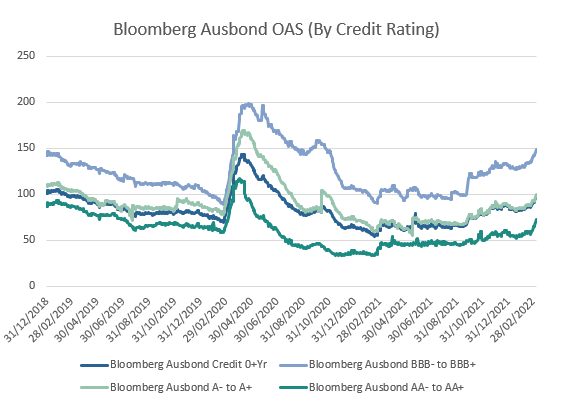

Credit spreads have endured a difficult start to the year, widening on the back of the same forces driving most risk assets – interest rates and the Russia/Ukraine conflict.

The last two years since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic has seen record low-interest rates and an unprecedented funding environment for issuers.

The deluge of liquidity pumped in by central banks buoyed credit markets and enabled corporates and financials to issue at size, and at longer tenors than usual.

Along with institutional fund flows through central bank support, more retail/wholesale investors also turned to credit for their fixed income allocation, given the relatively low levels of yields available through government bonds and term deposits.

Source: Mason Stevens, Bloomberg, as at 9/3/22

In 2022, as central bank policy has progressed to tighten once again, the picture for credit investors has been a little less positive.

Whilst investment-grade issuers remain well capitalised, rising interest rates have caused a relative decline in overall credit quality given the reduced serviceability of existing debts, and the increased costs of seeking new financing – overall a slight uptick in probability of default and/or loss..

Conflict between Russia and Ukraine, and downward revisions of economic growth forecasts have also pushed credit spreads wider in recent weeks as investors rush to the safety of cash and safe-haven assets.

The upcoming commencement of Quantitative Tightening (QT) activities from major central banks is also set to play a key role within fixed income markets over the medium term, with the pace, magnitude and focus of such activities set to drive levels of flows in and out of the asset class.

Back to Basics

Before we delve deeper, lets recap how credit spreads function.

For anyone who already has a general understanding – skip ahead to the next section.

Credit spreads represent the difference in yield between the relevant benchmark (usually government bonds) and the yield of another non-government debt security of the same maturity.

i.e. A 5y Westpac issued bond yields 3% p.a. while 5y government bonds yield 2% p.a., where the credit spread or risk premium for buying a Westpac bond is 1% p.a. (conventionally quoted as +100bp)

They reflect the risk premia which investors apply to the debt of the issuer, relative to government debt.

They make up one of the main components of fixed income markets – the other being the interest rates of benchmark securities.

Within equity markets, the focus lies primarily on the cash flows of a company, however, in credit markets, the focus is placed on the likelihood of that company being able to service interest payments and repay debt.

As a result, the underlying concerns are considerably different when compared to equity markets, with other factors such as levels of issuance also playing a role on relative valuations through the forces of supply and demand.

Quantitative Tightening and Credit Spreads

Whilst the Russia-Ukraine conflict has taken the limelight over the past few weeks, credit spreads are likely to continue to be driven by central bank policy action in the short-medium term.

In particular, the pace and focus of the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet reduction policy will play a meaningful role in driving global credit spreads, where Jerome Powell has currently stated that the QT process will proceed in a predictable manner, primarily through adjustments to reinvestments.

At Mason Stevens, we believe that this will involve a bias towards a reduction in MBS assets held on the Fed’s balance sheet, a form of “qualitative easing” which will see US MBS credit spreads widen materially.

Given the duration of the underlying MBS assets is typically around 30 years, this will have a markedly more apparent impact on longer dated tenors.

This will also see US corporate credit spreads widen as bank balance sheets are impacted by the increased funding costs within their MBS businesses, and as investors divert flows into the higher yielding MBS markets.

Whilst not to the same magnitude, Australian credit spreads will widen given the higher yields available abroad.

Foreign issuers will likely continue to issue in Australia given the favourable funding environment, although the size of the Australian market will restrict those with larger funding requirements.

The RBA’s approach to QT will also have an impact on Australian credit spreads, although Governor Lowe’s more dovish stance, and his lack of forward guidance on QT plans to date should result in US QT policy having a greater impact in the near term.

Caveats must also be made with the above analysis, as it assumes that the Fed will proceed in line with their existing forward guidance.

The Fed’s QT plans could be delayed or derailed by a number of events, including a worsening in economic conditions, global energy supply chain issues borne from the Russia-Ukraine conflict, and better than expected recoveries in inflation.

After all – the Fed has one reason to tighten (inflation), but a million reasons not to.

Last Drinks at the Liquidity Party

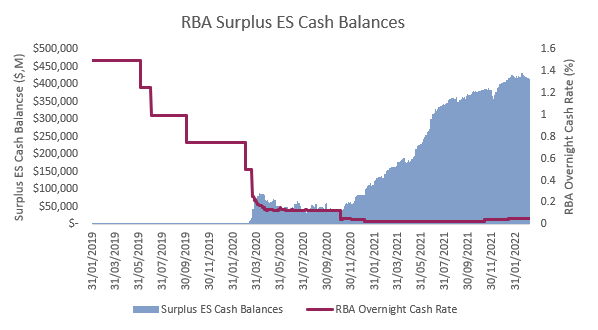

Throughout the duration of the RBA’s TFF program, Australian banks took advantage of the cheap funding available – seeing ESA cash balances rise to record levels and reducing the role of debt markets for short term financing.

This has created distortions within short term funding markets and played a role in compressing credit spreads throughout the curve, however, conditions will soon begin to normalise with the bulk of TFF maturities falling between September 2023 and June 2024.

Source: Mason Stevens, Bloomberg

As these maturities fall and in conjunction with QT activities, ES cash balances will materially decline, where banks will be more reliant on funding markets to meet liquidity requirements, driving spreads wider and closer to historical levels.

On the positive side, banks will also have increased demand for semi’s and government bonds, partially offsetting declining demand from the RBA.

Cash or Credit?

With declining economic growth prospects and the tightening of monetary policy from central banks around the world, the outlook for fixed income markets is less rosy.

However, most of what has caused market volatility in the past few months has been tied to interest rate movements – with this trend unlikely to change in the near future.

Floating rate notes (FRN’s) have remained relatively unaffected, where widening credit spreads have largely been offset by commensurate increases in coupon yields (higher running yields).

FRN’s remain a valuable defensive exposure for well-rounded portfolios, providing reliable and consistent income.

The credit quality of investment-grade (IG) issuers has largely remained unchanged, with Australian major banks continuing to be some of the most well capitalised financial institutions in the world.

These two viewpoints underscore our view of favouring floating rate notes and quality IG issuers in these times of elevated uncertainty.

Should you have any questions or would like to discuss our views further, please feel free to reach out to your Mason Stevens representative.

The views expressed in this article are the views of the stated author as at the date published and are subject to change based on markets and other conditions. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Mason Stevens is only providing general advice in providing this information. You should consider this information, along with all your other investments and strategies when assessing the appropriateness of the information to your individual circumstances. Mason Stevens and its associates and their respective directors and other staff each declare that they may hold interests in securities and/or earn fees or other benefits from transactions arising as a result of information contained in this article.