There was once a period of time where government bonds provided the desired income that investors required to meet their objectives.

I’m talking about when “govies” used to yield 4% p.a. or higher, basically any time before the last 10 years.

For example, the below chart depicts the yield to maturity (YTM) of 5-year Australian Commonwealth Government bonds (ACGB) over the last 22 years.

As those yields decreased over time, reflecting the lower economic growth and disinflationary macro environment, investors have increasingly re-allocated to other forms of fixed income to improve the overall yield and income of their portfolios.

This was done in many different ways.

One way was to buy foreign currency denominated bonds, where markets such as New Zealand, USA, UK, China etc. have had compelling bond yields over the years, that were attractive to Australian-based investors.

Another main avenue was to buy non-government issued bonds, issued by corporate entities (credit bonds).

This has become an investment staple for a large cohort of Australian investors, certainly since the RBA lowered the Overnight Cash Rate (OCR) below 1.5% in H2 2019.

What is credit?

When we assess credit bonds, we identify two major factors that influence the return from a fixed income investors’ perspective:

1. Interest rate risk

Interest rate risk measures the sensitivity of a bond’s price to movements in market interest rates. Specifically, this refers to various “risk-free rates”, or the yield of comparable government bonds, where the yields have moved lower and lower.

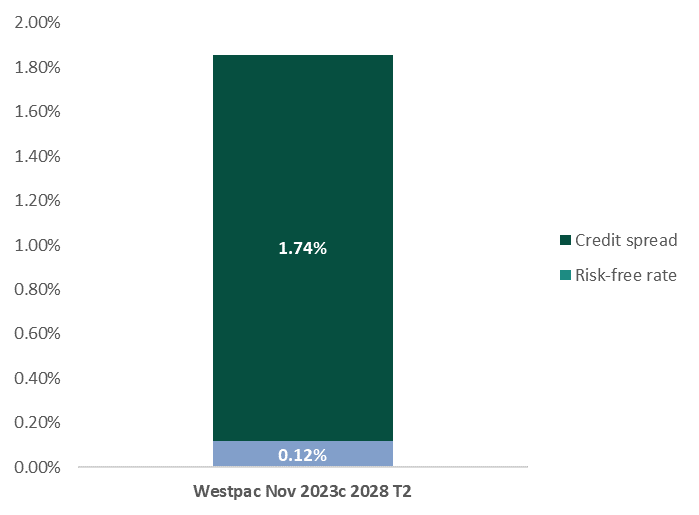

Credit spread is the premium investors receive for buying corporate issued bonds, rather than government bonds.

In the below example, an investor buying this Westpac bond would receive 1.74% premium compared to buying a Commonwealth government issued bond of the same tenor.

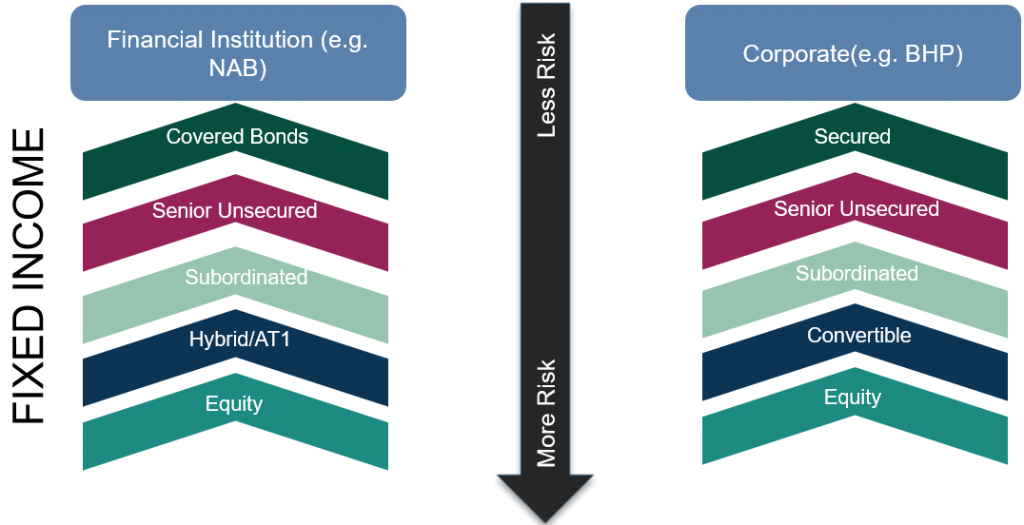

Capital structure

There is a catch to this.

The bonds that supply these yields above government bonds often have different terms that make them less vanilla to government bonds, where the nuances of the terms can differ, bond to bond.

This is because these bonds are not all senior unsecured debt obligations, they may be subordinated debt or convertible/hybrid debt.

Hence, the bond market becomes more opaque and specific knowledge is required to navigate the investment opportunities.

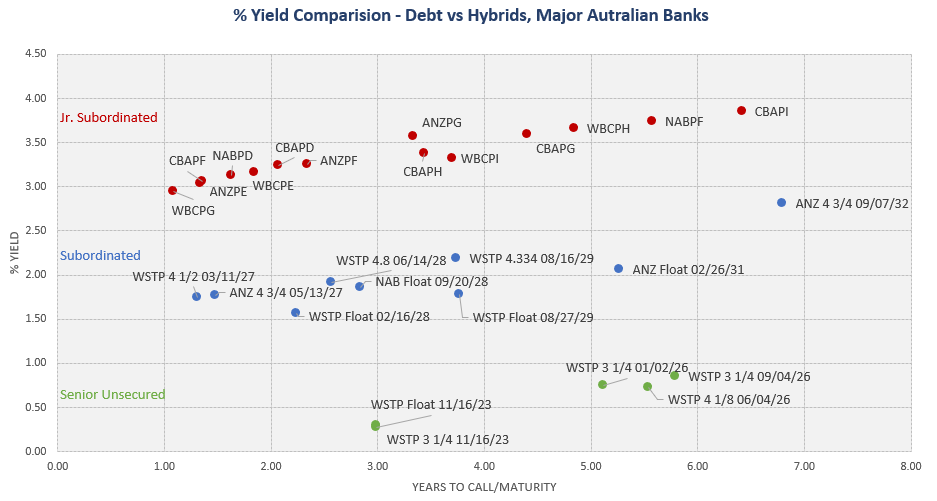

To highlight this point, the below depicts the different yields an investor may gain access to, investing in AUD:

- Senior unsecured debt (green)

- Subordinated debt (blue); or

- Junior subordinated, or “hybrid” debt (red)

There is a clear distinction between the risk and return of the various ranks of debt obligations (bonds).

What is a callable bond?

The knowledge gap that I wish to address today is what call dates mean to fixed income investors.

A call date is a day on which a bond’s issuer (i.e. Westpac, BHP, Scentre etc) may redeem the bond at a specific price, prior to the bond’s stated maturity date. Price is usually par or 100c/$.

The call date(s) and any such related terms are always known upfront, before the bond is issued in primary markets, so that lenders (bond buyers) can assess the risk and return of the investment.

In some cases, fixed income securities may not have a maturity date, they may be perpetual in nature – such as most ASX-listed bank hybrids – and their call dates are very relevant for investors to derive a yield.

Fixed maturity, call date example

For example, I refer to the Westpac bond I mentioned earlier.

The subordinated debt security was issued by Westpac in 2018, with a 10-year maturity date, callable in 5 years from issuance (“10NC5”)

- Issued in November 2018

- Maturity in November 2028

- Callable in November 2023

This means that Westpac has the option to call and redeem the bond in 2023 and is incentivised to do so by investors and credit rating agencies.

Perpetual bond, call date example

As an example, for a fixed income security with no maturity, let’s use Macquarie Group’s latest hybrid offering, MQGPE.

This security has no maturity date as it’s a perpetual “hybrid” instrument, issued to provide Macquarie with equity capital credit, and hence is perpetual similar to an equity investment.

The security will be:

- Issued in March 2021

- Have no fixed maturity

- Callable in September 2027 and subsequently every quarter afterwards until September 2030, where if not called, will convert into ordinary shares of Macquarie Group (Perp, NC6.5)

Yield to Call (YTC) and Yield to Maturity (YTM)

Yield to Call is a financial term that refers to the return a bondholder receives if the bond is held until the call date.

Yield to Maturity is another term that refers to the return a bondholder received if the bond is held until the maturity date.

Mathematically, they are calculated using the same method, but differ in the term (the value for t).

P = (C / 2) x {(1 – (1 + YTC / 2) ^ -2t) / (YTC / 2)} + (CP / (1 + YTC / 2) ^ 2t)

In the Westpac example above, YTC would derive the percentage return until November 2023, whereas YTM would calculate the return until November 2028.

Doing the math:

Current market price = 108.903c

YTC = 1.66% p.a.

YTM = 2.71% p.a.

Quite a big difference, based on the assumption that Westpac will call the bond at par, in November 2023.

Example – when call dates matter

To tie off this note regarding call dates and bond mechanics, I want to mention the specific example that’s arisen, that has made us think about this recently – though there are many.

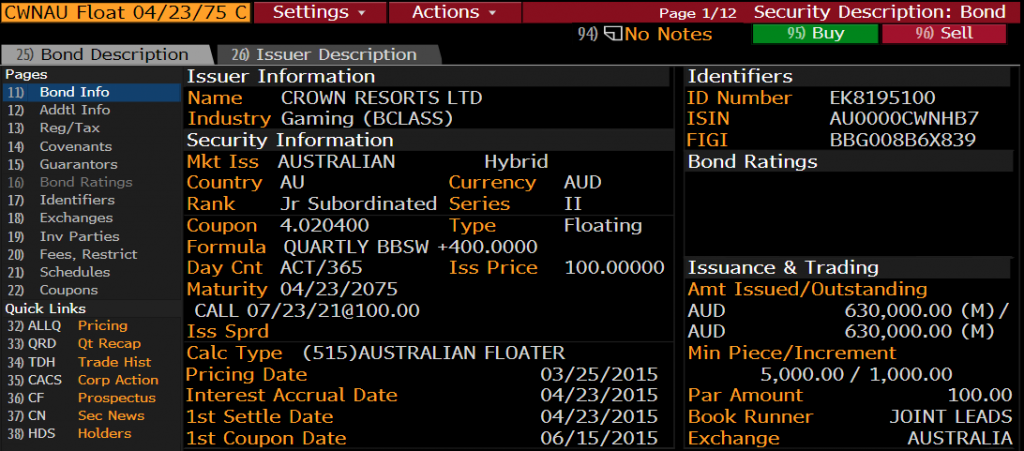

Crown Resorts has an ASX listed hybrid trading under the ticker CWNHB.

- Issued on 23 April 2015

- Maturity date 23 April 2075 (54 years from now)

- 1st call date 23 July 2021 (5 months from now)

- At the current market price of 91.44c

- YTM = 3m BBSW + 4.61% p.a.

- YTC = 3m BBSW + 63.51% p.a., (yep, that number isn’t a typo)

What is the market saying?

The market is pricing in that Crown in this instance will not be calling this security at the upcoming first call date in July, and more likely call it in a year or more later.

You could also say that the market is pricing in 50% chance the security is called at 100c or par, or 50% chance the security isn’t called and sells-off down to ~80c/$.

However, if you did buy this security at 91.44c and Crown did call it, you would be redeemed at 100c (par) in July and make 9.3% capital gain in ~5 months or 22.3% annualised – not too shabby.

Closing remarks

Instances of market volatility as well as isolated idiosyncratic risk make bond mathematics more interpretive art than science.

Last year, we saw this in several hybrid issuances from NAB and Macquarie, but also in Challenger’s CGFPA which was not called for over 6 months after it’s first call date.

This year, we’re seeing it in several USD hybrids issued by the likes of Bank of America and Citi, as well as the Crown example listed above – epitomising the idiosyncratic bond issuer risks.

The answer is awareness and knowledge, where investors are empowered by their knowledge of fixed income nuances and can better assess risk in portfolios.

One thing that is virtually “for sure”, subordinated bonds and hybrids will gain increasing allocation as investors seek higher yields in the absence of income from government bonds.

The views expressed in this article are the views of the stated author as at the date published and are subject to change based on markets and other conditions. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Mason Stevens is only providing general advice in providing this information. You should consider this information, along with all your other investments and strategies when assessing the appropriateness of the information to your individual circumstances. Mason Stevens and its associates and their respective directors and other staff each declare that they may hold interests in securities and/or earn fees or other benefits from transactions arising as a result of information contained in this article.